EN BANC

[ G.R. No. 211089, July 11, 2023 ]

SPOUSES DR. JOHN O. MALIGA AND ANNIELYN DELA CRUZ MALIGA, PETITIONERS, VS. SPOUSES ABRAHIM N. TINGAO AND BAI SHOR TINGAO, RESPONDENTS.

[G.R. No. 211135]

SPOUSES DR. JOHN O. MALIGA AND ANNIELYN DELA CRUZ MALIGA, PETITIONERS, VS. DIMASURANG UNTE, JR., RESPONDENT.

SEPARATE CONCURRING OPINION

DIMAAMPAO, J.:

The crux of the instant controversy revolves around the propriety of the Shari’ah District Court's dismissal of the complaints1 filed by petitioners. In doing so, the Shari’ah District Court held:

The parties in the above-titled cases clearly entered into contracts of loan with agreed interest rates. Unlike the Civil Code where there are provisions that govern transactions involving payment of interest. Presidential Decree No. 1083, the Code on Muslim Personal Laws does[sic] not contain any provision regarding any transaction/contract involving payment of interests. Laws on the matter have yet to be codified and incorporated in the present Muslim Code via an amendment to the same.

While the Acting Presiding Judge is aware that "Islam permits increase in capital through trade x x x x Islam blocks the way for anyone who tries to increase his capital through lending on usury or interest (riba), whether it is at low or a high rate x x x x", he dismissed the first case and will also dismiss the second case for lack of jurisdiction.

To reiterate, the parties entered into contracts of loan with agreed interest rates, hence, although verbally made, they are binding between and among them. The applicable laws should be applied to them by the proper court and therefore, this court is not the proper forum for the parties.2

At the incipience, I applaud the Court's efforts in strengthening Shari’ah justice by enriching Islamic jurisprudence through the instant ponencia. In this regard, I express my full concurrence thereto, and offer several points worth considering: first, the Shari’ah District Judge's unwarranted refusal to take cognizance of the complaint; second, the need for a specialized court to settle the present cases; and, third, a clarion call to fill the gaps in the existing Shari’ah legal framework, particularly those pertaining to Islamic finance.

The Shari’ah District Judge cannot decline to rule on the complaints on the simple pretext that Presidential Decree No. 1083 has no provision on transactions involving payment of interest or riba.

To ingeminate the words of the esteemed ponente, "x x x x [J]urisdiction, once acquired, is retained until the end of litigation. The applicable law or the validity of the contract at issue is immaterial. They do not bear on the issue of jurisdiction, much less divest the SDC of the same."3

Article 187 of Presidential Decree (PD) No. 1083,4 better known as the Code of Muslim Personal Laws, provides for the suppletory application of the Civil Code of the Philippines (Civil Code), the Rules of Court, and other existing laws, insofar as they are not inconsistent therewith. Corollary thereto, Article 9 of the Civil Code reads:

No judge or court shall decline to render judgment by reason of the silence, obscurity or insufficiency of the laws.

Here, the Shari’ah District Judge dismissed petitioners' complaints for lack of jurisdiction, since they involved the application of Act No. 26555 or the Usury Law.

An insightful perusal of PD No. 1083 glaringly evinces that it does not explicitly disallow the application of the Usury Law. There is also no mention of prohibition on interest or riba.1aшphi1 Certainly, the suppletory application of the Usury Law or the Civil Code, as the case may be, is not inconsistent with the provisions of the Code of Muslim Personal Laws.

To be sure, the mere application of a law other than PD No. 1083 does not justify the outright dismissal of a complaint filed before the Shari’ah courts. At risk of redundancy, no judge shall decline to render judgment by reason of the silence, obscurity, or insufficiency of the laws. On this ground alone, the Shari’ah District Judge should not have dismissed herein petitioners' complaints.

The Shari’ah District Judge, having acquired specialized expertise in Islamic law and jurisprudence, must resolve the complaints considering that petitioners invoked the Last Sermon of the Prophet Muhammad.

Shari’ah courts were originally conceived in the 1976 Tripoli Agreement6 for Muslim Filipinos in areas of the Autonomy "to set up their own Courts which will implement the Islamic Shari’ah laws."7 While the terms of the 1976 Tripoli Agreement were not implemented, PD No. 1083 gave it life by creating courts of limited jurisdiction such as the Shari’ah District Court and the Shari’ah Circuit Court, both of which fall under the administrative supervision of this Court.8

On that score, Article 140 of PD No. 1083 requires Shari’ah District Judges to have been engaged in the practice of law for at least ten years or has held a public office requiring admission to the practice of law as an indispensable requisite in addition to being learned in Islamic law and jurisprudence. At present, Republic Act (RA) No. 11054,9 or the Organic Law for the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, requires all Shari’ah judges to be regular members of the Philippine Bar, in addition to having completed at least two years of Shari’ah or Islamic Jurisprudence.10

Tellingly, Shari’ah judges developed an exclusive expertise in issues concerning Shari’ah by reason of their qualifications and by the very nature of their functions. This expertise becomes all the more apparent when conventional civil laws and rules of procedures are juxtaposed with the Ijra-at Mahakim al-Shari’ah, or the Special Rules of Procedure Governing the Shari’ah Courts, and the provisions of PD No. 1083.

This specialized expertise finds significance in these consolidated cases.1aшphi1

Literally, riba means excess. By virtue of RA No. 11439,11 riba, in the context of banking business, refers to the receipt and payment of interest, including in the various types of lending and borrowing and in the exchange of currencies on forward basis.12 The prohibition on riba in the conventional concept of interest comes from the practice of earning profit on money, without any goods or services being rendered.

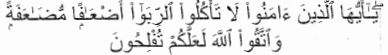

In proscribing riba, the Qur'an which is the ultimate source of Shari’ah, declares:

"O believers! Do not consume interest, multiplying it many times over. And be mindful of All, so you may prosper." (Al-Qur'an 3:130)

This divine revelation was echoed by the Prophet Muhammad  in his Last Sermon when he said, thusly: "Allah

in his Last Sermon when he said, thusly: "Allah  has forbidden you to take usury, therefore all interest obligation shall henceforth be waived. Your capital is yours to keep. You will neither inflict nor suffer any inequality. Allah

has forbidden you to take usury, therefore all interest obligation shall henceforth be waived. Your capital is yours to keep. You will neither inflict nor suffer any inequality. Allah  has judged that there shall be no interest and that all interest due to Abbas Ibn 'Aal-Muttalib be waived."

has judged that there shall be no interest and that all interest due to Abbas Ibn 'Aal-Muttalib be waived."

In the instant case, petitioners invoked the Last Sermon in seeking the accounting of the monies received by respondents, extinguishment of their obligations, and reimbursement of excess payments.13 Surely, the grounds relied upon by petitioners call for the application of a specialized knowledge in the field of Shari’ah which judges of conventional civil courts are not equipped with. Logic, thus, dictates that Shari’ah judges, having acquired specialized expertise in the field of Islamic law and jurisprudence, interpret the provisions of the Qur’an and the Prophetic practices (Sunnah), and apply them pertinently to the cases before them. No such expectation can be had from civil court judges who are neither required to be Shari’ah counselors-at-law nor enjoined to acquire knowledge of Islamic law and jurisprudence.

The need to fill the gaps in legislation concerning Islamic financial and commercial transactions to attain equal and inclusive justice.

Notwithstanding the passage of RA No. 11439, the current efforts to institutionalize the prohibition on riba, while indeed commendable, leave much to be desired. As previously enunciated, these legislative gaps do not absolve the courts from adjudicating disputes relative to such issue. In sooth, the Qur’an and the Sunnah already provide a comprehensive code of conduct for Muslim Filipinos governing the various facets of their lives, including financial transactions. The principles of equity, fairness, and justice enshrined in Shari’ah demand that the tenets from the primary sources of Shari’ah14 be applied in resolving cases involving riba.

All the same, the Court can only do so much in the face of inadequate specific legislation. Justice for every Filipino cannot simply come from the Judiciary but from the concerted endeavors of all sectors of the Government. This controversy presents a unique opportunity for the Court to direct the legislature's attention to the conspicuous gaps in the prevailing Shari’ah legal framework. In joining the ponencia's call for equal and inclusive justice,15 I strongly urge the Philippine Congress and other relevant stakeholders to expedite the enactment or adoption of more robust measures encompassing the promotion and protection of Islamic financial and commercial transactions, among others.

Given the foregoing disquisitions, I humbly vote to GRANT the consolidated Petitions.

Footnotes

1 Rollo (G.R. No. 211089), pp. 21-27; Rollo (G.R. No. 211135), pp. 21-36.

2 Rollo (G.R. No. 211135), pp. 42-44.

3 Decision, p. 12.

4 A DECREE TO ORDAIN AND PROMULGATE A CODE RECOGNIZING THE SYSTEM OF FILIPINO MUSLIM LAWS, CODIFYING MUSLIM PERSONAL LAWS, AND PROVIDING FOR ITS ADMINISTRATION AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES. Approved on February 4, 1977.

5 AN ACT FIXING RATES OF INTEREST UPON LOANS AND DECLARING THE EFFECT OF RECEIVING OR TAKING USURIOUS RATES AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES. Approved on February 24, 1916.

6 THE AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES AND MORO NATIONAL LIBERATION FRONT WITH THE PARTICIPATION OF THE QUADRIPARTITE MINISTERIAL COMMISSION MEMBERS OF THE ISLAMIC CONFERENCE AND THE SECRETARY GENERAL OF THE ORGANIZATION OF ISLAMIC CONFERENCE. Done in the City of Tripoli on 2nd Muharram 1397 H. corresponding to 23rd December 1976 A.D.

7 Paragraph 3, 3rd Agreement.

8 Article 137, PD No. 1083.

9 AN ACT PROVIDING FOR THE ORGANIC LAW FOR THE BANGSAMORO AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO, REPEALING FOR THE PURPOSE REPUBLIC ACT NO. 6734. ENTITLED "AN ACT PROVIDING FOR AN ORGANIC ACT FOR THE AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO," AS AMENDED BY REPUBLIC ACT NO. 9054, ENTITLED "AN ACT TO STRENGTHEN AND EXPAND THE ORGANIC ACT FOR THE AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO." Approved on July 27, 2018.

10 Section 8, Article X, RA No. 11054.

11 AN ACT PROVIDING FOR THE REGULATION AND ORGANIZATION OF ISLAMIC BANKS. Approved on August 22, 2019.

12 Section 2(a)(7), RA No. 11439.

13 Rollo (G.R. No. 211135), p. 32, and Rollo (G.R. No. 211089), pp. 24-25.

14 Under Section 3, Article X. RA No. 11054, the Qur’an, along with the Sunnah, are the primary sources of Shari’ah.

15 Decision, p. 2.

The Lawphil Project - Arellano Law Foundation