Manila

EN BANC

[ G.R. No. 211089, July 11, 2023 ]

SPOUSES DR. JOHN O. MALIGA AND ANNIELYN DELA CRUZ MALIGA, PETITIONERS, VS. SPOUSES ABRAHIM N. TINGAO AND BAI SHOR TINGAO, RESPONDENTS.

[G.R. No. 211135]

SPOUSES DR. JOHN O. MALIGA AND ANNIELYN DELA CRUZ MALIGA, PETITIONERS, VS. DIMASURANG UNTE, JR., RESPONDENT.

D E C I S I O N

ZALAMEDA, J.:

This case reaffirms the strengthened role of Shari'ah courts in our judicial system. Through this Decision, the Court underscores that Shari'ah courts are autonomous bodies which do not need to lean on regular civil courts. Our collective aspiration is for such self-reliance to be a tool towards equal and inclusive justice. As emphasized by Chief Justice Alexander G. Gesmundo in the recently concluded 1st National Shari'ah Summit, strengthening the Shari 'ah justice system improves genuine access to justice. Our hope is for Filipinos from all walks of life to attain redress undeterred by traditional barriers of inequality, such as education, wealth, gender, geography, ethnicity, and even religion. With this goal in mind, We finally dispel any lingering doubts on the broad jurisdiction of Shari'ah courts.

The Case

Before the Court are consolidated Petitions1 filed under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court seeking to annul and set aside the Order2 dated 08 July 2013 and Order3 dated 13 December 2013 of the 5th Shari'a District Court (SDC), Cotabato City, in the consolidated cases for Accounting, Restitution or Reimbursement with Damages and Attorney's Fees (Complaint), docketed as SDC Civil Case No. 2013-187 and SDC Civil Case No. 2013-188.

Antecedents

Between February 2009 and October 2012, petitioner Annielyn Dela Cruz Maliga (Annielyn) obtained a series of loans from respondent Dimasurang Unte, Jr. (Unte). The verbal contract of loan was initially for ₱110,000.00, with a monthly interest of 15%. The proceeds of the loan received by Annielyn was ₱93,000.00 after Unte deducted the first monthly interest of 15% in advance. Thereafter, Annielyn obtained further loans from Unte. Even as Unte increased the interest to 25% per month, Annielyn continued to pay until she could no longer do so even the interest. Despite Annielyn's predicament, Unte continued to demand payments from her.4

In 2009, Annielyn also obtained a loan from respondent spouses Abrahim N. Tingao and Bai Shor Tingao (Spouses Tingao). The verbal loan transaction was for ₱330,000.00 with an agreed monthly interest rate of 10%. Spouses Tingao released the proceeds of the loan after deducting the advance interest for one month amounting to ₱33,000.00. Annielyn tried her best to religiously pay the interest on said loan.5

Sometime in early 2013, however, petitioner Dr. John O. Maliga (Dr. Maliga), Annielyn's husband, discovered the alleged usurious loan transactions of his wife. Dr. Maliga also learned that Annielyn had been using his personal checks and the checks of his pharmacy to pay the loans to Unte and Spouses Tingao (collectively, respondents).6

By Dr. Maliga's computation, Annielyn's total payments to Unte had already reached ₱8,660,250.00 for interests alone, despite the principal amount of her loan being only ₱1,965.000.00.7 On the other hand, Annielyn's payments to Spouses Tingao had supposedly reached the amount of ₱1,452,000.00 on interest alone.8

Dr. Maliga thus asked his wife to stop paying Unte and Spouses Tingao. However, respondents continued to demand payments from Dr. Maliga and Annielyn (collectively, petitioners), prompting them to file separate complaints before the SDC against respondents.9 Petitioners prayed, in the main, for the extinguishment of the loans contracted by Annielyn, as well as the refund or restitution by respondents of all excess payments she had made.10

Unte filed a Motion to Dismiss11 SDC Civil Case No. 2013-187. He argued that the subject of the complaint was a verbal contract of loan involving the amount of more than ₱500.00, which called for the application of the Statute of Frauds under the New Civil Code. Hence, the regular courts, not the SDC, have jurisdiction over the complaint.12

Ruling of the SDC

Initially, the SDC issued an Order13 dated 08 July 2013, dismissing the complaint in SDC Civil Case No. 2013-187. The court agreed with Unte that the court lacked jurisdiction over the subject matter of the complaint since it involves the application of Act No. 265514 or the Usury Law. The SDC held that while a motion to dismiss is disallowed under the Special Rules of Procedure in Shari'a Courts, the same admits of an exception, such as when it is palpable that the court has no jurisdiction over the subject matter of the complaint, as in this case. Also, while the parties are Muslims, the transactions involved lending on usury or interest (riba), which is prohibited under the Shari'a.15

Aggrieved, petitioners filed a Motion for Reconsideration.16 However, the resolution of the motion was held in abeyance as petitioners and Unte tried to amicably settle their dispute. After settlement efforts fell through, the parties jointly moved for the resolution of the motion for reconsideration. Meanwhile, Spouses Tingao filed their own Motion to Dismiss17 in SDC Civil Case No. 2013-188, essentially raising the same argument as Unte.

Acting on the incidents, the SDC issued the now assailed Order, the dispositive portion of which reads:

WHEREFORE, the motion for reconsideration in the first case, Civil Case No. 2013-187, is DENIED. The complaint in the second case, Civil Case No. 2013-188, is DISMISSED without prejudice to its refiling before the proper forum.

SO ORDERED.18

The SDC ruled that, since the parties are Muslims, they may invoke Article 143(2)(b)19 of Presidential Decree No. (PD) 1083,20 or the Code of Muslim Personal Laws of the Philippines. However, the SDC ratiocinated that, while the contract was lending on usury or interest, a prohibited act under the Shari'a or Muslim laws, Annielyn and respondents nevertheless agreed on the same; hence, the agreement binds them. Corollarily, unlike the New Civil Code, PD 1083 has no provision regarding transactions involving payment of interest and the issue must thus be resolved under the Usury Law, the Civil Code, and other special laws by the civil courts, not by the SDC.21

Consequently, petitioners filed the instant consolidated petitions before this Court.

Issue

For the Court's resolution is whether or not the SDC correctly dismissed the complaints for lack of jurisdiction.

Ruling of the Court

The Court GRANTS the Petition.

Petitioners bewail the abrupt dismissal of their complaints, contending that the SDC palpably erred in concluding that it has no jurisdiction over the subject matter of the complaints because of the lack of applicable law under PD 1083 to adjudicate the consequences of the usurious nature of the transactions between the parties.

We agree with petitioners.

Jurisdiction of the court is conferred by law and is determined from the allegations in the complaint and the character of the relief sought

Jurisdiction is the power of a court, tribunal, or officer to hear, try, and decide a case.22 It is conferred by law. Absent a statutory grant, the actions, representations, declarations, or omissions of a party will not serve to vest jurisdiction over the subject matter in a court, board, or officer.23

In Foronda-Crystal v. Lawas Son,24 the Court categorically stated that:

In law, nothing is as elementary as the concept of jurisdiction, for the same is the foundation upon which the courts exercise their power of adjudication, and without which, no rights or obligation could emanate from any decision or resolution.25

It is settled that to determine which court has jurisdiction over the action, an examination of the complaint is essential. The nature of an action, and which court or body has jurisdiction over it, is determined based on the allegations in the complaint, regardless if the plaintiff is entitled to recover upon all or some of the claims asserted therein. The averments in the complaint and the character of the relief sought are controlling.26 "Once vested by the allegations in the complaint, jurisdiction also remains vested irrespective of whether or not the plaintiff is entitled to recover upon all or some of their claims."27

Jurisdiction of Shari'a District Courts

Matters over which Shari'a District Courts have original jurisdiction were enumerated in PD 1083.28 Art. 143 thereof provides:

Article 143. Original jurisdiction.

(1) The Shari'a District Court shall have exclusive original jurisdiction over:

(a) All cases involving custody, guardianship, legitimacy, paternity and filiation arising under this Code;

x x x x

(c) Petitions for the declaration of absence and death and for the cancellation or correction of entries in the Muslim Registries mentioned in Title VI of Book Two of this Code;

(d) All actions arising from customary contracts in which the parties are Muslims, if they have not specified which law shall govern their relations; and

(e) All petitions for mandamus, prohibition, injunction, certiorari, habeas corpus, and all other auxiliary writs and processes in aid of its appellate jurisdiction.

(2) Concurrently with existing civil courts, the Shari'a District Court shall have original jurisdiction over:

(a) Petitions by Muslims for the constitution of a family home, change of name and commitment of an insane person to an asylum;

(b) All other personal and real actions not mentioned in paragraph 1 (d) wherein the parties involved are Muslims except those for forcible entry and unlawful detainer, which shall fall under the exclusive original jurisdiction of the Municipal Circuit Court; and

(c) All special civil actions for interpleader or declaratory relief wherein the parties are Muslims or the property involved belongs exclusively to Muslims.29

Notably, with the enactment of Republic Act No. (RA) 11054,30 otherwise known as the Organic Law for the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, those actions where the SDC had concurrent jurisdiction with the civil courts have already been considered as within the exclusive and. original jurisdiction of the SDCs in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region, Section 6, Article X of said RA provides:

Section 6. Jurisdiction of the Shari'ah District Courts. - The Shari'ah District Courts in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region shall exercise exclusive original jurisdiction over the following cases where either or both are Muslims: Provided, That the non-Muslim party voluntarily submits to its jurisdiction:

(a) All cases involving custody, guardianship, legitimacy, and paternity and filiation arising under Presidential Decree No. 1083;

x x x x

(d) All actions arising from customary and Shari'ah compliant contracts in which the parties are Muslims, if they failed to specify the law governing their relations;

x x x x

(f) Petition for the constitution of a family home, change of name, and commitment of an insane person to an asylum;

(g) All other personal and real actions not falling under the jurisdiction of the Shari'ah Circuit Courts wherein the parties involved are Muslims, except those for forcible entry and unlawful detainer, which shall fall under the exclusive original jurisdiction of the Municipal Trial Court;

(h) All special civil actions for interpleader or declaratory relief wherein the parties are Muslims residing in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region or the property involved belongs exclusively to Muslim and is located in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region;

(i) All civil actions under Shari'ah law enacted by the Parliament involving real property in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region where the assessed value of the property exceeds Four hundred thousand pesos (₱400,000.00); and

(j) All civil actions, if they have not specified in the agreement which law shall govern their relations where the demand or claim exceeds Two hundred thousand pesos (₱200,000.00). (Emphasis supplied.)

Generally, jurisdiction is determined by the statute in force at the commencement of the action, unless a statute provides for retroactive application.31 Once jurisdiction attaches, it continues until the case is finally terminated.32 Since this case was filed prior to the effectivity of RA 11054 on 10 August 2018,33 and RA 11054 did not provide for retroactive application, PD 1083 remains to be the applicable law of this case insofar as jurisdiction is concerned.

The SDC has jurisdiction over the subject matter of the complaint

Under Art. 143(1) of PD 1083 the SDC has original jurisdiction over the complaint if it is sufficiently alleged that: (1) the action arose from a customary contract; (2) the parties are Muslims; and (3) the parties have not specified which law shall govern their relations:

As to actions not involving customary contracts, Art. 143(2)(b) of PD 1083 provides that these may still be adjudicated by SDCs provided that the parties are Muslims. Thus, the SDC may exercise concurrent jurisdiction with the civil court when the following conditions are met: (1) the complaint is a personal or real action, but not one for forcible entry or unlawful detainer; (2) the parties are Muslims; and (3) the action does not fall under Art. 143(1)(d) of PD 1083.34

In effect, Art. 143(2)(b) of PD 1083 acts as a catch-all provision that primarily hinges jurisdiction on the parties involved, and does not limit the jurisdiction of SDCs to specific kinds of action. Thus, regardless of the subject matter of the action, the SDC may exercise jurisdiction so long as the parties are Muslims.

The ruling in The Municipality of Tangkal, Lanao Del Norte v. Judge Balindong35 is instructive:

The matters over which Shari'a district courts have jurisdiction are enumerated in the Code of Muslim Personal Laws, specifically in Article 143. Consistent with the purpose of the law to provide for an effective administration and enforcement of Muslim personal laws among Muslims, it has a catchall provision granting Shari'a district courts original jurisdiction over personal and real actions except those for forcible entry and unlawful detainer. The Shari'a district courts' jurisdiction over these matters is concurrent 'with regular civil courts, i.e., municipal trial courts and regional trial courts. There is, however, a limit to the general jurisdiction of Shari'a district courts over matters ordinarily cognizable by regular courts: such jurisdiction may only be invoked if both parties are Muslims. If one party is not a Muslim, the action must be filed before the regular courts.36 (Citations omitted)

The concurrent jurisdiction of the SDC has practical and legal implications. First, it means that the plaintiff has a choice of forum between the SDCs or the regular civil courts, provided that both or all parties are Muslims.

Second, once a party exercises his or her choice of forum and files an action, such court shall retain jurisdiction until it finally disposes of the case. Once jurisdiction is vested, the same is retained up to the end of the litigation.37 This is also known as the doctrine of adherence of jurisdiction.38

Thus, once acquired, jurisdiction operates to exclude all other courts with concurrent jurisdiction from acting on the same case until a decision is finally rendered and executed. As held by the Court in Atty. Cabili v. Judge Balindong,39 "a court that acquires jurisdiction over the case and renders judgment therein has jurisdiction over its judgment, to the exclusion of all other coordinate courts, for its execution and over all its incidents, and to control, in furtherance of justice, the conduct of ministerial officers acting in connection with this judgment."40

Third, so long as the jurisdictional requirements are met, the SDC may adjudicate cases ordinarily cognizable by regular courts. These include cases where the applicable law may not be found in PD 1083, such as, for instance, an ordinary action for recovery of possession and ownership of a parcel of land.41 In Villagracia v. Fifth Sharia District Court,42 the Court, in discussing the concurrent jurisdiction of the SDC, stated that the latter, if found to have jurisdiction over the subject matter of the case, may apply laws of general application like the Civil Code, thus:

In real actions not arising from contracts customary to Muslims, there is no reason for Shari'a District Courts to apply Muslim law. In such real actions, Shari'a District Courts will necessarily apply the laws of general application, which in this case is the Civil Code of the Philippines, regardless of the court taking cognizance of the action. This is the reason why the original jurisdiction of Shari'a District Courts over real actions not arising from customary contracts is concurrent with that of regular courts.43

Similarly, in this case, the supposed lack of applicable provision on interest under PD 1083 per se does not deprive the SDC of jurisdiction over the subject matter.

Despite being courts of limited jurisdiction,44 SDCs are expected to have the same proficiencies and competencies as regular courts. In fact, Article 140 of PD 1083 provides that "[n]o person shall be appointed Shari'a District judge unless, in addition to the qualifications for judges of Courts of First Instance [now Regional Trial Courts] fixed in the Judiciary Law, he [or she] is learned in Islamic law and jurisprudence." This requirement was retained in RA 6734,45 and likewise, in RA 9054.46 More recently, RA 1105447 laid down specific qualifications for SDC judges within the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region, which are substantially similar to those for Regional Trial Court judges, i.e., Philippine Bar membership with at least ten (10) years of law practice.48 The law only imposed the additional qualification of completing at least two years of Shari'a or Islamic Jurisprudence.49

Thus, in addition to their specific expertise on Muslim law and customary law, the SDCs are equipped with the same capabilities as regular courts. By including a catchall provision on all personal and real actions, the law dearly intended the SDCs to be self-sufficient adjudicatory bodies able to effectively resolve any dispute between and among Muslims. This policy direction is further amplified in RA 11054, which, as mentioned, already vested SDCs with exclusive original jurisdiction over all other personal and real actions involving Muslims.

Notably, the goal of further empowering SDCs was extensively discussed during the 1st National Shari'ah Summit, which was aptly entitled "Forging the Role of Shari'ah in the National Legal Framework." As emphasized by Chief Justice Gesmundo, through the Court's Strategic Plan for Judicial Innovations (SPJI) 2022-2027, the Court endeavors to strengthen the Sharia'ah justice system, not only in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, but also in other areas where members of the Muslim population reside. Thus, further studies will be conducted on the expansion of the mandate of Shari'ah courts, such as the inclusion of both criminal and commercial cases, and the overall performance of the Sharia'ah justice system. The Court will also identify the strengths and weaknesses in various aspects of the Sharia'ah justice system that promote or hinder their efficiency or effectiveness. As further clarified by Senior Associate Justice Marvic M.V.F. Leonen, Chairperson of the Committee on Access to Justice in Underserved Areas and of the Technical Working Group on Shari'ah, the SPJI includes reforms on the Shari'ah as well as its rules of procedure. The 1st National Shari'ah Summit is only an initial engagement. The Court has a series of programs all aimed at supporting the Shari'ah justice system. These ongoing efforts are consistent with the Court's treatment of SDCs in this ruling.

Circling back to this case, the Court is not in a position to rule whether the contracts in dispute may be considered customary. The records are insufficient to arrive at a definitive ruling on this point. Beyond the instances provided for in the Muslim Code, the applicable Muslim law or 'äda is a question of fact.50

Here, the parties have yet to present evidence as the assailed ruling involves a resolution of a motion to dismiss. Thus, it would be premature to determine whether the contracts are customary.

Moreover, We are of the view that this is a matter that should first be resolved by the Shari'a courts. Even Muslim scholars have various ways of treating customs as a source of Islamic law. Hence, the Court is ill-equipped to define customary contracts considering the Court's limited viewpoint.

Indeed, if the Court were to truly empower SDCs, our jurisprudence on the scope of customary contracts must organically originate from them. This is a part of the Moros' right to self-determination, i.e., to shape their own laws and jurisprudence without the Court imposing our own perspectives even before the SDCs have been given a chance to rule on the issue.

In any event, a perusal of both complaints shows that petitioners sufficiently alleged a cause of action within the jurisdiction of the SDC. The complaints aver that the subject transactions both involve contracts of loan with interest. Petitioners prayed, inter alia, for the extinguishment of the loans contracted by Annielyn and the refund or restitution by respondents of all overpayments.51 Thus, the case is a personal action as it is founded on privity of contracts and seeks the recovery of personal property.52 Neither complaint is for forcible entry or unlawful detainer. Moreover, the complaints allege that petitioners and respondents are Muslims, which satisfies the requirement in Article 144(2)(6) of PD 1083.

Clearly, the SDC has jurisdiction over the subject matter of petitioners' complaints.

The SDC erred in shirking from its responsibility to hear and decide the case based on the perceived absence of applicable Muslim law on the subject controversy

With the foregoing, the Court finds that the SDC gravely erred in ruling that it is devoid of jurisdiction to hear the cases at bar merely for lack of an applicable provision under PD 1083 to specifically resolve the controversy between the parties, thus:

The parties in the above entitled cases clearly entered into contracts of loan with agreed interest rates. Unlike the Civil Code where there are provisions that govern transactions involving payment of interest, Presidential Decree [No.1aшphi1 1083,] the Code on Muslim Personal Laws[,] does not contain any provision regarding any transaction/contract involving payment of interests. Laws on the matter have yet to be codified and incorporated in the present Muslim Code via an amendment to the same.53

As earlier discussed, jurisdiction, once acquired, is retained until the end of litigation. The applicable law or the validity of the contract at issue is immaterial. They do not bear on the issue of jurisdiction, much less divest the SDC of the same. PD 1083 does not limit the SDC's jurisdiction to actions involving the application of this law's provisions. On the contrary, the catchall provision grants SDCs jurisdiction over nearly all personal and real actions between Muslims. Thus, even assuming that the case would require the application of certain civil law concepts and other special laws, the dispute must still be resolved by the SDC.

It is also notable that the SDC contradicted itself in ruling that there is no applicable Muslim law yet emphasizing that the transactions are prohibited under the Shari'a. The supposed prohibition evinces the existence of an applicable Muslim law.

Indeed, that there is no applicable provision in PD 1083 does not mean there is no relevant Muslim law to settle the dispute. The SDC failed to consider that PD 1083 only codified Muslim personal laws, i.e., laws applicable to personal and family matters such as civil personality, marriage and divorce, paternity and filiation, parental authority, support, and succession.54 This, therefore, explains the obvious lack of a particular provision, not only on payment of interest on loan transactions, but also of other laws governing transactions between one Muslim and another Muslim outside of the family. In fact, it is also possible for parties to point to a relevant Muslim law, not expressly stated in PD 1083, which must be proved in evidence as a fact. Article 5 of PD 1083 recognizes this, to wit:

ARTICLE 5. Proof of Muslim law and 'äda. — Muslim law and 'äda not embodied in this Code shall be proven in evidence as a fact. No 'äda which is contrary to the Constitution of the Philippines, this Code, Muslim law, public order, public policy or public interest shall be given any legal effect. (Emphasis supplied.)

Since the parties have yet to undergo pre-trial and adduce evidence on the applicable law, it was premature for the SDC to peremptorily rule that Muslim law prohibits the transactions. The existence of such prohibition and its effect on Annielyn's ability to recover overpayments are questions of fact for which evidence must be received. As held by the Court in Mangondaya v. Ampaso55 the questions whether the customary law or 'äda exists and whether it applies to the parties' situation are questions of fact.56

In the same case, the Court also found error on the part of the SDC when it summarily dismissed the case based only on the contents of the complaint and answer. In the order assailed therein, the SDC premised the dismissal on laches, prescription, and the invoked 'äda's supposed contravention of the Constitution, laws, and public policy. The Court ruled, thus:

Indeed, it was erroneous for the SDC to peremptorily conclude, on the basis of the parties' pleadings and their attachments, that petitioner failed to prove his claim over the land, that prescription and laches have set in, and that the 'äda, assuming it exists, is contrary to the constitution, laws and public policy. Had the SDC proceeded with the pre-trial and trial of the case, the parties would have had the opportunity to define and clarify the issues and matters to be resolved, present all their available evidence, both documentary and testimonial, and cross-examine, test and dispel each other's evidence. The SDC would, in turn, have the opportunity to carefully weigh, evaluate, and scrutinize them and have such sufficient evidence on which to anchor its factual findings. What appears to have happened though is a cursory determination of facts and termination of the case without the conduct of full-blown proceedings before the SDC. We affirm the following observation on the Special Rules of Procedure in Shari'a Courts:

When the plaintiff has evidence to prove his claim, and the defendant desires to offer defense, trial on the merits becomes necessary. The parties then will prove their respective claims and defenses by the introduction of testimonial (shuhud) and other evidence (bayyina). The statements of witnesses submitted at the pre-trial by the parties shall constitute the direct testimony as the basis for cross-examination.

In view of the foregoing, we remand the case to the SDC for the conduct of pre-trial and further proceedings for the reception of evidence in order for it to thoroughly examine the claims and defenses of the parties, their respective evidence and make its conclusions after trial on the merits. (Emphasis supplied.)

We arrive at the same conclusion here. Further proceedings are necessary to thresh out the applicable law, the validity and enforceability of the contracts, as well to determine whether respondents are liable for the alleged excess payments. It was therefore erroneous to dismiss the case based merely on a perceived lack of applicable Muslim law.

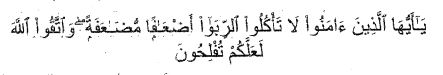

As aptly observed by Associate Justice Japar B. Dimaampao, petitioners invoked the Last Sermon in praying for a reimbursement of their alleged excess payments to respondents.57 In this Last Sermon, Prophet Muhammad (image supposed to be here) said "Allah (image supposed to be here) has forbidden you to take usury, therefore all interest obligation shall henceforth be waived. Your capital is yours to keep. You will neither inflict nor suffer any inequality. Allah (image supposed to be here) has judged that there shall be no interest and that all interest due to Abbas Ibn 'Aal-Muttalib be waived."58 Moreover, in proscribing riba, the Qur'an mentions:

"O believers! Do not consume interest, multiplying it many times over. And be mindful of All, so you may prosper. " (Al-Qur'an 3:130)

At this stage, it is premature to adjudicate the applicability of the cited doctrines. However, the SDC should have granted petitioners the opportunity to present evidence on the invoked Last Sermon and to argue its relevance to their case, As also emphasized by Justice Dimaampao, "the grounds relied upon by petitioners call for the application of a specialized knowledge in the field of Shari'ah which judges of conventional civil courts are not equipped with." This required expertise supports the continued exercise of jurisdiction by the SDC.

Lastly, even assuming that the transactions are prohibited under Muslim law or the contracts are unenforceable pursuant to the Statute of Frauds, the cases should still be adjudicated by the SDC. The SDC's acquisition of jurisdiction is not dependent on the merits of petitioners' complaints but on the allegations therein. Since the requisites for the SDC to acquire jurisdiction over the subject matter of the complaint were sufficiently alleged by petitioners, the SDC must hear and decide the consolidated cases, regardless of whether or not petitioners can ultimately prove their causes of action since jurisdiction remains vested irrespective of whether petitioners are entitled to recover upon all or some of the claims asserted therein.59

From the foregoing, the Court finds that the SDC erred in dismissing the complaints below for lack of jurisdiction. Hence, a remand is in order.

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the consolidated Petitions are GRANTED. The Order dated 13 December 2013 is is REVERSED and SET ASIDE. The consolidated cases are REMANDED to the court of origin for continuation of proceedings. The 5th Shari'ah District Court, Cotabato City, is DIRECTED to hear the consolidated cases with utmost dispatch.

SO ORDERED.

Gesmundo, C.J., Caguioa, Hernando, Lazaro-Javier, Inting, M. Lopez, Gaerlan, Rosario, J. Lopez, Marquez, Kho, Jr., and Singh, JJ., concur.

Leonen, SAJ., and Dimaampao, J., see separate concurring opinion.

Footnotes

1 Rollo, G.R. No. 211135, pp. 4-17.

2 Id. at 96; penned by Acting Presiding Judge Rasad G. Balindong.

3 G.R. No. 211089, pp. 41-42; penned by Acting Presiding Judge Rasad G. Balindong.

4 G.R. No. 211135, pp. 21-30.

5 G.R. No. 211089, pp. 21-22.

6 Id. at 22.

7 G.R. No. 211135, pp. 22-31.

8 G.R. No. 211089, pp. 23-24.

9 Id. at 22-23.

10 Id. at 24-25.

11 G.R. No. 211135, pp. 77-81.

12 Id. at 77-80.

13 Id. at 91.

14 Entitled "AN ACT FIXING RATES OF INTEREST UPON LOANS AND DECLARING THE EFFECT OF RECEIVING OR TAKING USURIOUS RATES AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES." Enacted: 24 February 1916.

15 G.R. No. 211135, p. 91.

16 G.R. No. 211089, pp. 41-42.

17 Id. at 29-33.

18 Id. at 42.

19 All other personal and real actions not mentioned in paragraph 1(d) wherein the parties involved are Muslims except those for forcible entry and unlawful detainer, which shall fall under the exclusive original jurisdiction of the Municipal Circuit Court.

20 Entitled: "A DECREE TO ORDAIN AND PROMULGATE A CODE RECOGNIZING THE SYSTEM OF FILIPINO MUSLIM LAWS, CODIFYING MUSLIM PERSONAL LAWS, AND PROVIDING FOR ITS ADMINISTRATION AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES." Dated: 04 February 1977.

21 G.R. No. 211089, p. 41.

22 Victoria Manufacturing Corporation Employees Union v. Victoria Manufacturing Corporation, 857 Phil. 673, 680 (2019).

23 Id. at 683.

24 821 Phil. 1033 (2017).

25 Id. at 1037.

26 See Padlan v. Dinglasan, 707 Phil. 83, 91 (2013); Emphasis supplied.

27 Id.

28 See The Municipality of Tangkal, Province of Lanao del Norte v. Judge Balindong, 803 Phil. 207, 215 (2017).

29 Id. at 215. Emphases supplied.

30 Entitled: "AN ACT PROVIDING FOR THE ORGANIC LAW FOR THE BANGSAMORO AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO, REPEALING FOR THE PURPOSE REPUBLIC ACT NO. 6734, ENTITLED "AN ACT PROVIDING FOR AN ORGANIC ACT FOR THE AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO," AS AMENDED BY REPUBLIC ACT NO. 9054, ENTITLED "AN ACT TO STRENGTHEN AND EXPAND THE ORGANIC ACT FOR THE AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO" Approved: 27 July 2018.

31 Baritua v. Mercader, 402 Phil. 932, 945 (2001).

32 Id.

33 See Dimapanat v. Hataman, G.R. No. 228726, 19 July 2022.

34 Entitled: "A DECREE TO ORDAIN AND PROMULGATE A CODE RECOGNIZING THE SYSTEM OF FILIPINO MUSLIM LAWS, CODIFYING MUSLIM PERSONAL LAWS, AND PROVIDING FOR ITS ADMINISTRATION AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES," Dated: 04 February 1977.

35 Supra note 27.

36 Id. at 215-216.

37 Sumawang v. Engr. De Guzman, 481 Phil. 239, 245-246 (2004).

38 See The Wellex Group, Inc. v. Sheriff Urieta, 785 Phil. 594, 633 (2016).

39 672 Phil. 398 (2011).

40 Id. at 407.

41 See The Municipality of Tangkal, Lanao Del Norte v. Judge Balindong, supra note 27; Mangondaya v. Ampaso, 828 Phil. 592 (2018).

42 734 Phil. 239 (2014).

43 Id. at 255.

44 PD 1083, Sec. 137.

45 AN ACT PROVIDING FOR AN ORGANIC ACT FOR THE AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO, Republic Act No. 6734 (1989). Art. IX, Sec. 13, reads:

SECTION 13. The Shari'ah District Courts and the Shari'ah Circuit Courts created under existing laws shall continue to function as provided therein. The judges of the Shari'ah courts shall have the same qualifications as the judges of the Regional Trial Courts, the Metropolitan Trial Courts or the Municipal Trial Courts as the case may be. In addition, they must be learned in Islamic law and jurisprudence.

46 AN ACT TO STRENGTHEN AND EXPAND THE ORGANIC ACT FOR THE AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO, AMENDING FOR THE PURPOSE REPUBLIC ACT NO. 6734, ENTITLED 'AN ACT PROVIDING FOR THE AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO', As AMENDED. Republic Act No. 9054 (2001). Art. VIII, Sec. 18, reads:

SECTION 18. Shari'ah Courts. — The Shari'ah district courts and the Shari'ah circuit courts created under existing law shall continue to function as provided therein. The judges of the Shari'ah courts shall have the same qualifications as the judges of the regional trial courts, the metropolitan trial courts or the municipal trial courts, as the case may be. In addition, they must be learned in Islamic law and jurisprudence.

47 AN ACT PROVIDING FOR THE ORGANIC LAW FOR THE BANGSAMORO AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO, REPEALING FOR THE PURPOSE REPUBLIC ACT NO. 6734, ENTITLED 'AN ACT PROVIDING FOR AN ORGANIC ACT FOR THE AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO', AS AMENDED BY REPUBLIC ACT NO. 9054, ENTITLED 'AN ACT TO STRENGTHEN AND EXPAND THE ORGANIC ACT FOR THE AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO.'"

48 RA 11054, Article X, Sec. 8 (b).

49 Id.

50 PD 1083, Art. 5.

51 G.R. No. 211135, pp. 32-33; G.R. No. 211089, pp. 24-25.

52 Tomawis v. Hon. Balindong, 628 Phil. 252, 262 (2010).

53 G.R. No. 211089, p. 41.

54 ARTICLE 7. Definition of terms. – Unless the context otherwise provides:

x x x x

(i) "Muslim Personal Law" includes all laws relating to personal status, marriage and divorce, matrimonial and family relations, succession and inheritance, and property relations between spouses and provided for in this Code.

55 828 Phil. 592 (2018).

56 Id. at 601.

57 See Separate Concurring Opinion, J. Dimaampao, p. 4.

58 Id. at 3-4.

59 See supra note 26, at 91-93.

The Lawphil Project - Arellano Law Foundation