EN BANC

[ G.R. No. 211089, July 11, 2023 ]

SPOUSES DR. JOHN O. MALIGA AND ANNIELYN DELA CRUZ MALIGA, PETITIONERS, VS. SPOUSES ABRAHIM N. TINGAO AND BAI SHOR TINGAO, RESPONDENTS.

[G.R. No. 211135]

SPOUSES DR. JOHN O. MALIGA AND ANNIELYN DELA CRUZ MALIGA, PETITIONERS, VS. DIMASURANG UNTE, JR., RESPONDENT.

SEPARATE CONCURRING OPINION

LEONEN, SAJ.:

I commend the ponencia and all the members of the Banc, through Chief Justice Alexander Gesmundo's leadership, for its efforts in strengthening the shari'ah1 justice system as part of the national legal framework.

This Court ought to revisit its interpretations of Presidential Decree No. 1083 (Muslim Code), and its intended inclusivity when it recognized the Islamic legal system as part of the law of the land. Statutes enacted after the Muslim Code recognizing the Moros' right to self-determination underscore how limited the Muslim Code's scope is in its express codification of a vast legal system it supposedly recognized. "While called shari'a courts in our jurisdiction, they primarily interpret personal and family laws only, which is but one aspect of shari'a."2 This case presents a unique opportunity to rectify the exclusion of shari'ah as part of the legal framework of our State, starting from a fundamental principle in our justice system, the court's jurisdiction.

The Muslim Code was ambiguous regarding the shari'ah courts' jurisdiction on other aspects of Islamic law that were not expressly codified. Here, what constitutes "customary contracts" were not clearly defined in the law. With the constitutional guarantee3 and consistent congressional intent,4 I submit that this Court may interpret the jurisdiction of Shari'a District Courts in Article 143(1)(d) of the Muslim Code on customary contracts as exclusive and original on all actions arising from contracts between Muslim parties who did not stipulate on which law shall govern their relations, to the exclusion of civil courts. This is in due recognition of the shari'ah judges' expertise to resolve matters requiring the application of Islamic laws, over which judges assigned in courts of general jurisdiction have no competence, and to give life to the Muslim Code provisions on adopting shari'ah as part of the law of the land.

I

The ponencia ruled that the Muslim Code applies here since the complaint was filed in 2013, before Republic Act No. 11054's effectivity.5 While I agree to a certain extent, I opine that this requires judicial construction, and a more circumspect review.

Jurisdiction over the subject matter is conferred by the Constitution or a statute. It is determined in the material allegations in the complaint and character of relief sought, whether the plaintiff is entitled to their claims.6

Generally, the law at the time of the filing of the action determines the subject matter jurisdiction.7 Statutes "altering the jurisdiction of a court cannot be applied to cases already pending prior to their enactment,"8 as the court has already obtained and is exercising jurisdiction over a controversy. An exception to this rule is when a retroactive application is expressly stated in the law, "or is construed to the effect that it is intended to operate as to actions pending before its enactment."9

Another exception to the non-retroactivity of the effect of an amendment is when the statute is curative in nature. These are statutes that rectify "defects in a prior law or to validate legal proceedings, instruments or acts of public authorities which would otherwise be void for want of conformity with certain existing legal requirements."10

As there is ambiguity in the laws on jurisdiction, a review of statutes creating the shari'ah courts and the Bangsamoro Justice System is necessary to determine the nature of jurisdiction of Shari'a District Courts.

Batas Pambansa Blg. 129 or the Judiciary Reorganization Act of 1980 does not define the jurisdiction of shari'ah courts. Instead, it refers to the creation of shari'ah courts under the Muslim Code and provides for their inclusion in appropriations.11

On February 4, 1977, Presidential Decree No. 1083 otherwise known as the "Code of Muslim Personal Laws" (Muslim Code) was enacted "to promote the advancement and effective participation" of Muslim Filipinos in national government. In the formulation and implementation of State policies, their customs, traditions, beliefs, and interests were finally considered.12 After many years of struggling against the hegemony of civil and common law traditions brought by our colonizers, and the complete neglect of the unique cultural and historical heritage of the Moros who had their sophisticated system of governance, Congress recognized that Moros' legal system, along with their primary sources of law,13 form part of the laws of the land. To stress, explicitly included in this recognition are the primary sources of shari'ah (Muslim law), the standard treatises and works on shari'ah and jurisprudence (fiqh), and the four Muslim schools of law (madhhab), namely the Hanafi, Hanbali, Maliki and Shafi'i.14

Despite the Muslim Code's noble purpose of making Islamic institutions more effective, only a portion of the otherwise comprehensive system of shari'ah was expressly codified. It covered personal law defined as "personal status, marriage and divorce, matrimonial and family relations, succession and inheritance, and property relations between spouses[.]"15 It created courts of limited jurisdiction, as well as the shari'a circuit courts and the shari'a district courts under the Supreme Court's administrative supervision,16 and conferred the courts' scope of jurisdiction.

Article 143 of the Muslim Code defines the exclusive and concurrent jurisdiction of shari'ah district courts:

Article 143. Original jurisdiction. — (1) The Shari'a District Court shall have exclusive original jurisdiction over:

(a) All cases involving custody, guardianship, legitimacy, paternity and filiation arising under this Code;

(b) All cases involving disposition, distribution and settlement of the estate of deceased Muslims, probate of wills, issuance of letters of administration or appointment of administrators or executors regardless of the nature or the aggregate value of the property;

(c) Petitions for the declaration of absence and death and for the cancellation or correction of entries in the Muslim Registries mentioned in Title VI of Book Two of this Code;

(d) All actions arising from customary contracts in which the parties are Muslims, if they have not specified which law shall govern their relations; and

(e) All petitions for mandamus, prohibition, injunction, certiorari, habeas corpus, and all other auxiliary writs and processes in aid of its appellate jurisdiction.

(2) Concurrently with existing civil courts, the Shari'a District Court shall have original jurisdiction over:

(a) Petitions by Muslims for the constitution of a family home, change of name and commitment of an insane person to an asylum;

(b) All other personal and real actions not mentioned in paragraph 1 (d) wherein the parties involved are Muslims except those for forcible entry and unlawful detainer, which shall fall under the exclusive original jurisdiction of the Municipal Circuit Court; and

(c) All special civil actions for interpleader or declaratory relief wherein the parties are Muslims or the property involved belongs exclusively to Muslims. (Emphasis supplied)

The Muslim Code is not the only law that prescribes the jurisdiction of shari'ah courts. I submit that An Act Providing for an Organic Act for the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) or Republic Act No. 6734, its subsequent amendment in Republic Act No. 9054, and both laws' subsequent repeal in Republic Act No. 11054 are relevant in determining the nature of jurisdiction of shari'a courts.

On August 1, 1989, Republic Act No. 6734, the first law providing for the Organic Act for the ARMM was enacted. It established ARMM as "truly reflective of their ideals and aspirations within the framework of the Constitution and national sovereignty, as well as the territorial integrity of the Republic of the Philippines."17 It provided basic regional government18 identified provinces voting in favor of their inclusion in a plebiscite.19

The grant of powers to the regional government in the ARMM was under the scheme of devolution from the national government through the regional assembly, the regional governor, and the special courts created by the law.20 Republic Act No. 6734 considers ARMM as a corporate entity with "powers, functions and responsibilities now being exercised by the departments of the National Government,"21 but removed certain powers such as foreign affairs, national defense, and administration of justice, among others. It created the Shari'ah Appellate Court, and prescribed its jurisdiction, its composition, and the qualification of its members.22 Significantly, the law affirmed the jurisdiction of shari'a courts under the Muslim Code.23

On March 31, 2001, Republic Act No. 9054 amended Republic Act No. 6734, expanding the ARMM and its regional powers. On the administration of justice, the law directs that whenever feasible at least one justice of the Supreme Court and two justices of the Court of Appeals from the autonomous region shall be appointed through the recommendations of the Regional Governor after proper consultations.24 The Office of the Deputy Court Administrator for ARMM25 and the Shari'ah Public Assistance Office26 were also created under the law.

Republic Act No. 9054 recognized the need to ensure mutual respect and protect the "beliefs, customs, and traditions of the people in the autonomous region."27 The Regional Assembly was directed to formulate the Shari'ah Legal System. Significantly, the law also directed the expansion of the jurisdiction of shari'a courts to not only include personal, family, and property relations, but also commercial transactions and criminal acts involving Muslims:

Section 5. Customs, Traditions, Religious Freedom Guaranteed. The beliefs, customs, and traditions of the people in the autonomous region and the free exercise of their religions as Muslims, Christians, Jews, Buddhists, or any other religious denomination in the said region are hereby recognized, protected and guaranteed.

The Regional Assembly shall adopt measures to ensure mutual respect for and protection of the distinct beliefs, customs, and traditions and the respective religions of the inhabitants thereof, be they Muslims, Christians, Jews, Buddhists, or any other religious denomination. The Regional Assembly, in consultation with the Supreme Court and consistent with the Constitution may formulate a Shari'ah legal system including the criminal cases which shall be applicable in the region, only to Muslims or those who profess the Islamic faith. The representation of the regional government in the various central government or national government bodies as provided for by Article V, Section 5 shall be effected upon approval of the measures herein provided.

The Shari’ah courts shall have jurisdiction over cases involving personal, family and property relations, and commercial transactions, in addition to their jurisdiction over criminal cases involving Muslims.

The Regional Assembly shall, in consultation with the Supreme Court, determine the number and specify the details of the jurisdiction of these courts.

No person in the autonomous region shall be subjected to any form of discrimination on account of creed, religion, ethnic origin, parentage or sex.

The regional government shall ensure the development, protection, and well-being of all indigenous tribal communities. Priority legislation in this regard shall be enacted for the benefit of those tribes that are in danger of extinction as determined by the Southern Philippines Cultural Commission. (Emphasis supplied)

The foregoing provision of Republic Act No. 9054 is an express recognition of the scope of shari'ah courts which includes commercial transactions and criminal cases involving Muslims. While the details of this jurisdiction was only enacted 17 years later on July 27, 2018 in Republic Act No. 11054, or the Organic Law for the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), this Court should not ignore this express directive from the Congress as a clear manifestation of its intent to modify the jurisdiction of shari'ah courts.

Espousing the Moros' right to self-determination, Republic Act No. 11054, more widely known as the Bangsamoro Organic Law, changed the system of devolution of regional government structure under Republic Act No. 6734 as amended, to a system of self-governance.28 It repealed the former organic act and its amendments.29 ARMM evolved from a corporate entity with limited devolved powers to BARMM, a political entity with the right to self-governance in its pursuit of "political, economic, social, and cultural development" under the Bangsamoro Organic Law.30 It significantly expanded the powers of the Bangsamoro government,31 and established the Bangsamoro Justice System founded on shari'ah for the Muslim and tribal laws of indigenous people in BARMM:

SECTION 1. Justice System in the Bangsamoro. — The Bangsamoro justice system shall be administered in accordance with the unique cultural and historical heritage of the Bangsamoro.

The dispensation of justice in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region shall be in consonance with the Constitution, Shari’ah, traditional or tribal laws, and other relevant laws.

Shari’ah or Islamic law forms part of the Islamic tradition derived from religious precepts of Islam, particularly the Qur'an and Sunnah.

Shari’ah shall apply exclusively to cases involving Muslims. Where a case involves a non-Muslim, Shari'ah law may apply only if the non-Muslim voluntarily submits to the jurisdiction of the Shari'ah court.

The traditional or tribal laws shall be applicable to indigenous peoples within the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region.

The provisions of this Article shall not prejudice the rights of non-Muslims and nonindigenous peoples.32

Under the Bangsamoro Organic Law, the jurisdiction of Shari'ah Circuit and District Courts were also amended:33

| Presidential Decree No. 1083 or the Code of Muslim Personal Laws (Muslim Code) |

Republic Act No. 11054 or the Bangsamoro Organic Law |

|

ARTICLE 143. Original jurisdiction. - (1) The Shari'a District Court shall have exclusive original jurisdiction over:

(a) All cases involving custody, guardianship, legitimacy, paternity and filiation arising under this Code;

(b) All cases involving disposition, distribution and settlement of the estate of deceased Muslims, probate of wills, issuance of letters of administration or appointment of administrators or executors regardless of the nature or the aggregate value of the property;

(c) Petitions for the declaration of absence and death and for the cancellation or correction of entries in the Muslim Registries mentioned in Title VI of Book Two of this Code;

(d) All actions arising from customary contracts in which the parties are Muslims, if they have not specified which law shall govern their relations; and

(e) All petitions for mandamus, prohibition, injunction, certiorari, habeas corpus, and all other auxiliary writs and processes in aid of its appellate jurisdiction.

(2) Concurrently with existing civil courts, the Shari'a District Court shall have original jurisdiction over:

(a) Petitions by Muslims for the constitution of a family home, change of name and commitment of an insane person to an asylum;

(b) All other personal and real actions not mentioned in paragraph 1 (d) wherein the parties involved are Muslims except those for forcible entry and unlawful detainer, which shall fall under the exclusive original jurisdiction of the Municipal Circuit Court; and

(c) All special civil actions for interpleader or declaratory relief wherein the parties are Muslims or the property involved belongs exclusively to Muslims.

|

SECTION 6. Jurisdiction of the Shari'ah District Courts. — The Shari'ah District Courts in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region_shall exercise exclusive original jurisdiction over the following cases where either or both are Muslims: Provided, That the non-Muslim party voluntarily submits to its jurisdiction:

(a) All cases involving custody, guardianship, legitimacy, and paternity and filiation arising under Presidential Decree No. 1083;

(b) All cases involving disposition, distribution, and settlement of the estate of deceased Muslims, probate of wills, issuance of letters of administration, or appointment of administrators or executors regardless of the nature or the aggregate value of the property;

(c) Petitions for the declaration of absence and death, and for the cancellation or correction of entries in the Muslim Registries mentioned in Title VI of Book Two of Presidential Decree No. 1083;

(d) All actions arising from customary and Shari'ah compliant contracts in which the parties are Muslims, if they failed to specify the law governing their relations;

(e) All petitions for mandamus, prohibition, injunction, certiorari, habeas corpus, and all other auxiliary writs and processes, in aid of its appellate jurisdiction;

(f) Petitions for the constitution of a family home, change of name, and commitment of an insane person to an asylum;

(g) All other personal and real actions not falling under the jurisdiction of the Shari'ah Circuit Courts wherein the parties involved are Muslims, except those for forcible entry and unlawful detainer, which shall fall under the exclusive original jurisdiction of the Municipal Trial Court;

(h) All special civil actions for interpleader or declaratory relief wherein the parties are Muslims residing in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region or the property involved belongs exclusively to Muslims and is located in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region;

(i) All civil actions under Shari'ah law enacted by the Parliament involving real property in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region where the assessed value of the property exceeds Four hundred thousand pesos (PHP 400,000.00); and

(j) All civil actions, if they have not specified in an agreement which law shall govern their relations where the demand or claim exceeds Two hundred thousand pesos (PHP 200,000.00). (Emphasis supplied)

The Shari'ah District Court in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region shall exercise appellate jurisdiction over all cases decided upon by the Shari'ah Circuit Courts in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region within its territorial jurisdiction, as provided under Article 144 of Presidential Decree No. 1083, as amended. (Emphasis supplied)

|

|

ARTICLE 155. Jurisdiction. — The Shari'a Circuit Courts shall have exclusive original jurisdiction over:

(1) All cases involving offenses defined and punished under this Code.

(2) All civil actions and proceedings between parties who are Muslims or have been married in accordance with Article 13 involving disputes relating to:

(a) Marriage;

(b) Divorce recognized under this Code;

(c) Betrothal or breach of contract to marry;

(d) Customary dower (mahr);

(e) Disposition and distribution of property upon divorce;

(f) Maintenance and support, and consolatory gifts, (mut'a); and

(g) Restitution of marital rights.

(3) All cases involving disputes relative to communal properties.

|

SECTION 5. Jurisdiction of the Shari'ah Circuit Courts. — The Shari'ah Circuit Courts in the Bangsamoro AutonomousRegion_shall exercise exclusive original jurisdiction over the following cases where either or both parties are Muslims: Provided, That the non-Muslim party voluntarily submits to its jurisdiction:

(a) All cases involving offenses defined and punished under Presidential Decree No. 1083, where the act or omission has been committed in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region;

(b) All civil actions and proceedings between parties residing in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region who are Muslims or have been married in accordance with Article 13 of Presidential Decree No. 1083, involving disputes relating to:

Marriage;

Divorce;

Betrothal or breach of contract to marry;

Customary dower or mahr;

Disposition and distribution of property upon divorce;

Maintenance and support, and consolatory gifts; and

Restitution of marital rights.

(c) All cases involving disputes relative to communal properties;

(d) All cases involving ta'zir offenses defined and punishable under Shari'ah law enacted by the Parliament punishable by arresto menor or the corresponding fine, or both;

(e) All civil actions under Shari’ah law enacted by the Parliament involving real property in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region where the assessed value of the property does not exceed Four hundred thousand pesos (PHP 400,000.00); and

(f) All civil actions, if they have not specified in an agreement which law shall govern their relations, where the demand or claim does not exceed Two hundred thousand pesos (PHP 200,000.00).

|

Notably, the Bangsamoro Organic Law removed the concurrent jurisdiction of existing civil courts under Article 143, paragraph 2 of the Muslim Code, and placed all these actions within the exclusive original jurisdiction of Shari'ah District Courts. This includes "all other personal and real actions not falling under the jurisdiction of the Shari'ah Circuit Courts wherein the parties involved are Muslims," except forcible entry and unlawful detainer.34

The Bangsamoro Organic Law expanded the Shari'ah District Courts' exclusive and original jurisdiction on all actions arising from any customary contracts under the Muslim Code to expressly include "Shari'ah compliant contracts" between Muslim parties who have not specified the law governing their relations. The law also recognized the power of BARMM's legislative department, its Parliament, to enact laws governing civil, commercial, and criminal matters which are not provided for under the Muslim Code.35

Considering these developments, it may be inaccurate to state that only the Muslim Code or Presidential Decree No. 1083 applies in the determination of jurisdiction of Shari'ah District Courts. The legislative history in the various amendments, repeal, and enactment of the present Bangsamoro Organic Law reflects the strong desire of Congress to carry out the policy of inclusivity that was first enunciated in Presidential Decree No. 1083. In the formulation and implementation of policies, the customs, traditions, beliefs and interests of the Muslims and indigenous peoples in Mindanao must be considered.36

Here, the ponencia discussed the subject matter of the complaint in relation to the scope of jurisdiction of Shari'ah District Court. It stated that the customary nature of the contract between the parties is irrelevant in determining jurisdiction because the records are insufficient to make a determinative ruling on the issue.37 In any case, it resorted to the catchall provision under Article 143(2)(6) of the Muslim Code in finding the concurrent jurisdiction of shari'a with civil courts, considering that the parties are all Muslims, and that the allegations in the complaint constitute a personal action for the recovery of monies.38 In ruling so, the ponencia gave importance to the plaintiff's choice on the forum. Since petitioners filed the action before the Shari'ah District Court, the ponente upheld its concurrent jurisdiction, which continues until the full disposition of the case.

I humbly propose that a different approach be employed when applying Article 143(1)(d) on customary contracts and determining whether the loan contracts involved fall under it. The ambiguity in the law must first be recognized, since "customary contracts" were not clearly defined in the law and may admit of an expansive definition.

While there is basis to resort to the catch all concurrent jurisdiction of shari'a courts under Article 143(2)(6) of the Muslim Code, I submit that at the core of jurisdiction is competence, or the ability of courts to resolve disputes presented before them. This is founded on the knowledge of the applicable law, the manner of construing and interpreting its provisions, and their application based on the factual antecedents and the evidence presented before them. Congress will not confer jurisdiction to courts mandating them to resolve cases outside of its competence.

In addition to recognizing the historical injustice on the narratives of the Moros and the unique cultural and historical heritage of the Bangsamoro, knowledge of Islamic law (shari'ah) and jurisprudence (fiqh) are necessary to resolve cases requiring the application of shari'ah in disputes involving Muslim parties. In my view, courts should avoid a literal construction of the provisions of the law conferring concurrent jurisdiction to regular courts that have no competence to resolve the cases entailing the application of Islamic laws. Courts of general jurisdiction have no competence in resolving shari'ah disputes as regular judges are not learned in Muslim law, as much as shari'ah judges are trained in laws of general application.

Respectfully, I submit that judicial construction is required in interpreting Article 143(1)(d) of the Muslim Code on what are customary contracts falling within the exclusive jurisdiction of Shari'a District Courts. I propose that this construction consider the historical context of the Moros and the legislative developments after the law that recognized the shari'ah legal system as part of the laws of the land. There has been consistent intent in expanding shariah courts' jurisdiction, which may include deeming customary contracts as a generic, catchall term over which shari'ah courts have exclusive jurisdiction.

Thus, I disagree with the ponencia that "it would be premature to determine whether the contracts are customary."39 I submit that this is an opportune time to decisively rule on determining what contracts fall under the exclusive original jurisdiction of Shari'a District Courts.

II

Generally, when the words in a statute are clear and unequivocal, they must be given their literal meaning without need of interpretation.40 The Congress deliberately chose the words of the law upon it, fully aware of their meaning. Thus, congressional intent is determined in the language of the law itself.41 However, when the "true intent of the law is clear ... such intent or spirit must prevail over the letter thereof, for whatever is within the spirit of a statute is within the statute."42 Courts should not resort to a literal construction of the law when there is imprecise language that defeats the purpose of the law, or results in absurdity or injustice.43

The interpretation that supports the spirit of the law must be followed where its policies prevail.44 The ambiguity in the law should be construed in relation to the other relevant portions of the law, with the interpretation that best resonates with reason and justice.45 In exceptional circumstances, when the literal interpretation of the text of the law contradicts its spirit and exposes an apparent omission in the language of the law which should have been included, judicial construction can supply the omission.46 This is to give effect to the obvious congressional intent and purpose of the law that is "clearly ascertainable from the context."47

A discussion of the basic foundations of Islamic law is necessary to distill the legislative intention on what customary contracts mean to determine the nature of the jurisdiction intended for Shari'ah District Courts.

Shari’ah is a "divine system of law." To Muslims, Allah (s.w.t.) is the sole authority who revealed Islam and its legal system through Prophet Muhammad. There are four sources of shari'ah: its principal sources from the Qur'an and the Sunnah as recorded in the hadiths, and secondary sources of Ijma or the juristic consensus, and Qiyas, or those derived from analogy;48 as recognized in the Muslim Code as forming part of the law of the land.49

Allah's infallible words in the Qur'an were revealed to Prophet Muhammad, gradually and intermittently, based on the current demands. Knowledge of the context and reason for the revelations are necessary in construing laws from the Qur'an.50 Aside from religious instructions, the Qur'an contains fundamental principles on the protection of Islamic faith, laws on family life and personal relations, civil and commercial laws, and penal laws.51 Islam, although with separate laws regulating worship, cannot be divorced from the laws regulating the relationship of persons. Shari'ah encompasses the entirety of a Muslim's life, both as an individual and as a community member.52 Adherence to shari'ah is a religious duty among Muslims, and it is considered as a personal law of every Muslim. Muslims believe that shari'ah governs them, wherever they may be residing, regardless of local laws.53

Interpretations and commentaries on the Qur'an have a complex set of rules which only believers can appreciate.54 Moreover, there are four major schools of law with varying doctrines on the application of shari'ah: The Hanafi, Hanbali, Maliki and Shafi'i,55 as likewise recognized under the Muslim Code.56

Prophet Muhammad, through his teachings and conduct, also known as the Sunnah, supplied the details and clarified some of the ambiguities in the Qur'an.57 His companions, their followers, and their subsequent followers, preserved the Prophet's teachings and narrated them in their respective generations. Later, they were compiled in writing. Since the Prophet's traditions were relayed from one person to another, the chain of narrators, or isnad, had to be verified as authentic. Aside from its authenticity, the text of the hadith, or the matn, was also examined to verify its consistency with the Qur'an and other traditions of Prophet Muhammad.58

Ijma is the "consensus of opinion" of Muslim jurists (mujtahideen) in a formal assembly where a particular question of law is presented. Agreement to the decision can be expressed through words or actions. Ijma may be proven with continuous notoriety among Muslims.59 On the other hand, Qiyas, or analogical reasoning, is a process of deduction based on an original subject in the Qur'an, Sunnah, or Ijma, which is extended and applied to a new subject not covered here.60

Ada, or customary law, refers to the collective, consistent, accepted, and binding practice of people in a particular place.61 These are not independent sources of shari'ah but the "force of general usage" is considered when there is no applicable text, and when the customs are not opposed to Islamic teachings.62 Muslim scholars have various ways of treating customs as a source of Islamic law which continue to evolve with the times.63 Other scholars treat customs as having the force of contract between the parties, which, even if not stipulated, have suppletory application when no conditions have been stipulated.64 Customs are extraneous sources of Islamic law.65 Thus, they are required to be proven in evidence as fact.66

At the risk of being repetitive, the Muslim Code or Presidential Decree No. 1083 was enacted to recognize "the legal system of the Muslims in the Philippines as part of the law of the land." It created shari'a courts and defined their jurisdiction for the "effective administration and enforcement of Muslim personal laws among Muslims." The law has inherent limits in recognizing the entire shari'ah system, and expressly codified a small portion of its laws. In my view, the limited scope of the law does not prevent this Court from reading the purpose for which Presidential Decree No. 1083 created shari'ah courts—to recognize a pluralistic legal system, weave the historical and cultural narrative of the Muslim people in the national consciousness, and provide for an effective administration and enforcement of Muslim laws.67

The express codification of only a small portion of shari'ah appears to create an ambiguity in the scope of exclusive and original jurisdiction of shari'a courts, as the Muslim Code has likewise recognized the primary sources of shari'ah. Since only personal laws were codified, the question of whether situations requiring the application of other aspects of Muslim law, especially those from the primary sources of shari'ah, that were not expressly codified are included within their exclusive and original jurisdiction.

There is no express provision in the Muslim Code which defines customary contracts.

The literal meaning of a custom is "a practice that by its common adoption and long, unvarying habit has come to have the force of law."68 By extension, a customary contract is an agreement based on accepted common practice in a locality. The Muslim Code mentions the following: customary dower (mahr),69 property relations between spouses,70 their household properties,71 offenses against customary law which can be settled without formal trial,72 customary heirloom,73 and "[a]ny transaction whereby one person delivers to another any real estate, plantation, orchard or any fruit bearing property by virtue of sanda, sanla, arindao, or similar customary contract[.]"74 Interestingly, any other customary law not mentioned in the Muslim Code may be proven in evidence as fact.75

In my view, customary contracts between Muslim parties under Article 143(1)(d) should not be literally read as to only cover the contracts enumerated in the law, to the exclusion of other contracts governed by the primary sources of shari'ah that the Code recognized. A literal interpretation of customary contracts defeats the purpose of the law in recognizing the entire legal system of Muslims in the Philippines, including the primary sources of Islamic law. Congress could not have intended to remove contracts governed by the Qur'an, Sunnah, Ijma, and Qiyas within the exclusive original jurisdiction of shari'a courts, especially since their interpretation and application as to questions of law require knowledge and expertise of Islamic laws, which courts of general jurisdiction do not possess.

In Villagracia v. Fifth Shari'a District Court,76 this Court rationalized the concurrent jurisdiction of shari'a courts with regular civil courts in relation to Article 143(2)(b) stating that Muslim law have no application in "actions not arising from contracts customary to Muslims"77 In the same manner, when the cause of action of Muslim parties is based on Islamic law, courts of general jurisdiction have no competence to resolve these cases. Thus, its resolution falls within the competence of shari'ah judges to the exclusion of other courts.

III

An examination of the complaint and the reliefs prayed for by petitioner show that the complaint requires the application of Islamic law, and thus within the competence of Shari'ah District Courts, to the exclusion of other tribunals.

The facts are simple. Petitioner Annielyn Maliga entered verbal loan contracts with respondent Dimasirang Unte, Jr. and respondent Spouses Abrahim and Bai Shor Tingao, agreeing to a 10% monthly interest on their respective loans. Annielyn received the loan proceeds net of the first monthly interest. She used the income of her husband's clinic to pay for her loans. When he found out about his wife's loans, petitioner John Maliga prevented her from further paying as the principal amounts have already been paid through the supposed interest.

Petitioners filed separate complaints for accounting, restitution, or reimbursement with damages and attorney's fees before the Fifth Shari'ah District Court of Cotabato City. They were seeking the following reliefs: first, the extinguishment of their loan contract based on payment; second, for the accounting of all payments made; and third, for the reimbursement of excess payments of interest, which is prohibited under Muslim law.78 As basis for the third cause of action, petitioners invoke the last sermon of Prophet Muhammad as follows:

13. Based on the foregoing, there is a necessity that an accounting be made as to the amounts collected and received by defendant spouses from Annielyn and consider the loan incurred extinguished. Furthermore, the total amount of interest which have been paid shall be equitably reduced or totally waived and restituted or reimbursed to herein plaintiffs in accordance with the Prophet Muhammad's (Peace Be Upon Him) words during his last Sermon delivered on the Ninth Day of Dhul Hijah, 10 A.H. In the Uranah Valley of Mount Arafat, pertinent portion of which is instructive and I quote:

"ALLAH has forbidden you to take usury (Interest), therefore all interest obligation shall henceforth be waived. Your capital, however, is yours to keep. You shall neither inflict nor suffer inequity. Allah has Judged that there shall be no interest and that all the interest due to Abbas ibn' Abd'al Muttalib shall henceforth be waived."79

Considering the foregoing facts and the reliefs prayed for in their complaint, I agree with the ponencia that the action involved is a personal one. Personal actions seek "to enforce personal rights and obligations brought against the defendant,"80 such as collection of a debt, personal duty, or damages.81 However, I do not agree that the personal action involved is based on customary contracts as the ponencia implies.82

In the Petitions, Spouses Maliga stated that they sought the filing of the complaints before the Shari'a District Court, invoking the Islamic law which "prohibits the increase of capital through usury or interest (riba), whether it is with high or low interest."83 They contend that the loan contracts were not themselves prohibited. It is only the accessory contracts of interest which are prohibited under the Islamic laws that they are seeking to annul.84

Indeed, loan transactions among Muslims are covered in the teachings of the Qur'an. Riba is defined as an increase (fadl) which accrues to a lender of a commodity which has no equivalent return ('iwad) to the other party.85 Riba is common in loans and sale of goods. The prohibition of riba cannot be construed as a customary law, as it is absolutely prohibited in the Qur'an, Sunnah, and Ijma as "an atrocious sin, and a heinous crime."86

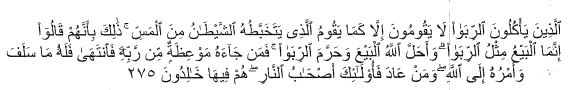

Without prejudice to my views on the separation of church and state,87 as it is not our concern here, the reality is that Presidential Decree No. 1083 or the Muslim Code "recognizes the legal system of the Muslims in the Philippines as part of the law of the land."88 The Muslim Code is law that expressly recognized the legal system of a minority. The Qur'an, the primary source of Islamic law, under Surah Al-Baqarah 2:275 provides:

(Those who devour usury shall not rise except as one rises who is felled by the touch of Satan. That is because they say, "Buying and selling are simply like usury," though God has permitted buying and selling and forbidden usury. One who, after receiving counsel from his Lord, desists shall have what is past and his affair goes to God. And as for those who go back, they are the inhabitants of the Fire, abiding therein.)89

Riba is prohibited because it causes various social, moral, and economic harm since the rich benefit at the expense of the poor.90 Hence, the prohibition on riba is not derived from a custom of general usage, but from a primary source of Islamic law. To stress, a contract with riba cannot be deemed customary.

I likewise agree with the ponencia that the Shari'a District Court should not have rejected its mandate in resolving the question of law which requires the application of Islamic law on the sole reason that there was nothing in the Muslim Code that can be applied.91 As repeatedly stressed, the law recognized the Muslim legal system, including the sources of shari'ah. While only the personal laws have been codified, the Muslim Code also directed that the construction and interpretation of its provisions should consider the primary sources of Muslim law and give persuasive effect to standard treatises and works on Muslim law and jurisprudence.92

Thus, I propose that even if it can be conceded that only the Muslim Code should be considered in the determination of subject matter jurisdiction of Shari'ah District Courts, customary contracts should not be construed based on its literal meaning to exclude the primary sources of shari'ah. Instead, customary contracts can be interpreted to mean as typical contracts entered by Muslims, considering that shari'ah prescribes fundamental laws relating to civil and commercial transactions with others.

In sum, to determine jurisdiction under the Muslim Code, the relevant consideration in contracts between Muslims is whether the parties have agreed to a particular law that will govern their transaction. When the parties did not, as in the case here, the loan contracts fall under Article 143(1)(d), over which the Shari'ah District Court has exclusive and original jurisdiction.

It is difficult to recognize the concurrent jurisdiction of civil courts on these types of contracts for which the Qur'an and Sunnah impose religious and therefore, legal obligations for Muslim parties. Regular courts do not have authority and expertise to interpret the words of the Qur'an and the actions of Prophet Muhammad. As fundamental sources of law, the Qur'an and the Sunnah will certainly be difficult to grasp for regular courts of general jurisdiction. While the Muslim Code conferred concurrent jurisdiction with regular courts, the judges' lack of knowledge and understanding of Islamic laws necessarily affects the exercise of jurisdiction and their dispensation of justice. Far from placing courts of general jurisdiction below the level of shari'ah courts, my view on the latter's exclusive jurisdiction on any dispute requiring the application of Islamic law is founded on the competence, knowledge, and ability of a judge to resolve the specific dispute presented before them.

Finally, I likewise note that there appears to be anomalies on jurisdiction under the Bangsamoro Organic Law.

First, it states, "[w]here a case involves a non-Muslim, Shari’ah law [sic] may apply only if the non-Muslim voluntarily submits to the jurisdiction of the Shari’ah court."93 However, it is the Muslim Code that applies to marriages, their nature, consequences, and incidents between a male Muslim and a non-Muslim solemnized in Muslim rites.94 This appears to mean that if the non-Muslim party to a Muslim marriage does not voluntarily submit to the shari'ah court's jurisdiction, her recourse would be in the regular courts. However, as likewise stressed, a regular court judge lacks competence to rule, for instance, on a civil action "relating to marriage; divorce; betrothal or breach of contract to marry; customary dower or mahr; disposition and distribution of property upon divorce; maintenance and support, and consolatory gifts; and restitution of marital rights"95 which call for an application of shari'ah. Perhaps, judicial construction may likewise be employed in a proper case. A non-Muslim agreeing to marry a Muslim solemnized in Muslim rites may be deemed to have voluntarily submitted to be governed by the Muslim Code and consequently, voluntarily submitted to the jurisdiction of the shari'ah court which has the competence to properly rule on matters relative to their marriage.96

Further, it is strange that while the BOL expressly amends the provisions on jurisdiction of shari'a courts under the Muslim Code,97 the jurisdictions of shari'ah circuit courts98 and shari'ah district courts99 under the Bangsamoro Organic Law appear to limit them to those "in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region" only. The ardent desire of this Court is for a strengthened shari'ah justice system and better access to justice for Muslims. A step is through the Congress' establishment of more shari'ah courts in the rest of the country where a significant number of Muslims reside, which may be outside the BARMM. Limiting the amendment of jurisdiction to shari'ah courts in the BARMM may have been an oversight.

ACCORDINGLY, I vote for the grant of the consolidated petitions, the reversal of the assailed order, the remand of the case to the Shari'ah District Court of Cotabato City, and the decisive pronouncement on the exclusive original jurisdiction of Shari'ah District Courts on all actions arising from contracts between Muslim parties who did not stipulate on which law shall govern their relations.

Footnotes

1 Spelled as "shari'a" in Presidential Decree No. 1083 otherwise known as "Code of Muslim Personal Laws in the Philippines." When not referring to the courts that the law created, it will be spelled as "shari'ah" here.

2 Malaki v. People, G.R. No. 221075, November 15, 2021 [Per J. Leonen, Third Division].

3 CONST., art. II, sec. 22 provides:

The State recognizes and promotes the rights of indigenous cultural communities within the framework of national unity and development.

CONST., art. XIV, sec. 17 provides:

SECTION 17. The State shall recognize, respect, and protect the rights of indigenous cultural communities to preserve and develop their cultures, traditions, and institutions. It shall consider these rights in the formulation of national plans and policies.

4 See Republic Act No. 6734; Republic Act No. 9054; and Republic Act No. 11054.

5 Ponencia, p. 8.

6 Villagracia v. Fifth Shari'a District Court, 734 Phil. 239, 251 (2014) [Per J. Leonen, Third Division].

7 Erectors, Inc. v. National Labor Relations Commission, 326 Phil. 640, 645 (1996) [Per J. Puno, Second Division].

8 Alarilla v. Sandiganbayan, 393 Phil. 143, 155-156 (2000) [Per J. Gonzaga-Reyes, Third Division].

9 Philippine National Bank v. Tejano, Jr., 619 Phil. 139, 147 (2009) [Per J. Peralta, En Banc].

10 Erectors, Inc. v. NLRC, 326 Phil. 640, 647 (1996) [Per J. Puno, Second Division].

11 Batas Pambansa Blg. 129, sec. 45 states:

SECTION 45. Shari'a Courts. — Shari'a Courts to be constituted as provided for in Presidential Decree No. 1083, otherwise known as the "Code of Muslim Personal Laws of the Philippines," shall be included in the funding appropriations so provided in this Act.

12 Whereas Clauses of Presidential Decree No. 1083.

13 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 4, par. 1.

14 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 6, par. 2.

15 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 7(i).

16 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 137.

17 Preamble of Republic Act No. 6734.

18 Republic Act No. 6734, art. I, sec. 2 states:

SECTION 2. It is the purpose of this Organic Act to establish the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, to provide its basic structure of government within the framework of the Constitution and national sovereignty and the territorial integrity of the Republic of the Philippines, and to ensure the peace and equality before the law of all people in the Autonomous Region.

19 Republic Act No. 6734, art. II, sec. 1, par. 2.

20 Republic Act No. 6734, art. IV, sec. 2.

21 Republic Act No. 6734, art. V, sec. 2(9).

22 Republic Act No. 6734, art. IX, secs. 3-5.

23 Republic Act No. 6734, art. IX, sec. 13 states:

SECTION 13. The Shari'ah District Courts and the Shari'ah Circuit Courts created under existing laws shall continue to function as provided therein. The judges of the Shari'ah courts shall have the same qualifications as the judges of the Regional Trial Courts, the Metropolitan Trial Courts or the Municipal Trial Courts as the case may be. In addition, they must be learned in Islamic law and jurisprudence.

24 Republic Act No. 9054, art. VIII, sec. 2.

25 Republic Act No. 9054, art. VIII, sec. 4.

26 Republic Act No. 9054, art. VIII, sec. 6.

27 Republic Act No. 9054, art. III, sec. 5.

28 Republic Act No. 11054, art. I, sec. 3.

29 Republic Act No. 6734, as amended by Republic Act No. 9054.

30 Republic Act No. 11054, art. IV, sec. 2.

31 Republic Act No. 11054, art. V, sec. 2.

32 Republic Act No. 11054, art. X, sec. 1.

33 Republic Act No. 11054, art. XVIII, sec. 4(d) states:

SECTION 4. Amendatory Clause. — (h) Upon the ratification of this Organic Law, the pertinent provisions of the following laws which are inconsistent with this Organic Law are hereby amended accordingly:

. . . .

(d) Articles 140, 143, 152, 153, 154, 164, 165, 166, 167 and 168 of Presidential Decree No. 1083, otherwise known as the "Code of Muslim Personal Laws of the Philippines[.]"

34 Republic Act No. 11054, art. X, sec. 6.

35 Republic Act No. 11054, art. X, sec. 4 provides:

SECTION 4. Power of the Parliament to Enact Laws Pertaining to Shari'ah. — The Parliament shall have the power to enact laws on personal, family, and property law jurisdiction.

The Parliament has the power to enact laws governing commercial and other civil actions not provided for under Presidential Decree No. 1083, as amended, otherwise known as the "Code of Muslim Personal Laws of the Philippines," and criminal jurisdiction on minor offenses punishable by arresto menor or ta'zir which must be equivalent to arresto menor or fines commensurate to the offense.

36 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 2.

37 Ponencia, p. 11.

38 Id. at 8.

39 Ponencia, p. 11.

40 Globe-Mackay Cable and Radio Corp. v. National Labor Relations Commission, 283 Phil. 649, 660 (1992) [Per J. Romero, En Banc].

41 Tańada v. Yulo, 61 Phil. 515, 518 (1935) [Per J. Malcolm, En Banc].

42 Hidalgo v. Hidalgo, 144 Phil. 312, 323 (1970) [Per J. Teehankee, En Banc].

43 Pobre v. Mendieta, 296 Phil. 634, 644 (1993) [Per J. Grińo-Aquino, En Banc].

44 Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Seagate Technology, 491 Phil. 317, 343 (2005) [Per J. Panganiban, Third Division].

45 Roa v. Insular Collector of Customs, 23 Phil. 315, 339 (1912) [Per J. Trent, First Division].

46 Matabuena v. Cervantes, 148 Phil. 295, 300 (1971) [Per J. Fernando, En Banc].

47 RUBEN E. AGPALO, STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION 232 (6th edition, 2009).

48 Republic Act No. 11054, art. X, sec. 3.

49 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 2, 4, par. 1, and 6.

50 BENSAUDI I. ARABANI, SR., COMMENTARIES ON THE CODE OF MUSLIM PERSONAL RELATIONS OF THE PHILIPPINES WITH JURISPRUDENCE AND SPECIAL PROCEDURE 79 (2011).

51 Id. at 81-82.

52 Id. at 55-60.

53 JAINAL D. RASUL, COMPARATIVE LAWS: THE FAMILY CODE OF THE PHILIPPINES AND THE MUSLIM CODE (1994).

54 BENSAUDI I. ARABANI, SR., COMMENTARIES ON THE CODE OF MUSLIM PERSONAL RELATIONS OF THE PHILIPPINES WITH JURISPRUDENCE AND SPECIAL PROCEDURE 86-103 (2011).

55 Id. at 33-50.

56 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 6.

57 BENSAUDI I. ARABANI, SR., COMMENTARIES ON THE CODE OF MUSLIM PERSONAL RELATIONS OF THE PHILIPPINES WITH JURISPRUDENCE AND SPECIAL PROCEDURE 110-111 (2011).

58 Id. at 117-126.

59 Id. at 158-173.

60 Id. at 174-176.

61 Commentary, p. 204.

62 Tahir Mahmood, Custom as a Source of Law in Islam. 7 JOURNAL OF THE INDIAN LAW INSTITUTE, 102, available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/43949882 (accessed May 29, 2023).

63 Gideon Libson, On the Development of Custom as a Source of Law in Islamic Law: Al-Ruju u Ila al-urfi Ahadu al-Qawa idi al-Khamsi Allati Yatabanna alayha al-Fiqhu, 4 ISLAMIC LAW AND SOCIETY 133, 141-142 (1997), available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/3399492 (accessed June 2, 2023).

64 Id. at 152-154.

65 BENSAUDI I. ARABANI, SR., COMMENTARIES ON THE CODE OF MUSLIM PERSONAL RELATIONS OF THE PHILIPPINES WITH JURISPRUDENCE AND SPECIAL PROCEDURE 264 (2011).

66 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 5.

67 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 2.

68 BLACK'S LAW DICTIONARY 1164 (8th edition, 2004).

69 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 13, par. 3., in relation to art. 15(d).

70 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 37(c).

71 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 43.

72 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 163.

73 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 173(a).

74 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 175.

75 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 5.

76 734 Phil 239 (2014) [Per J. Leonen, Third Division].

77 Id. at 255.

78 Rollo (G.R. No. 211089), p. 24.

79 Id.

80 WILLARD B. RIANO, CIVIL PROCEDURE (THE BAR LECTURES SERIES) 186-187 (Volume I, 2011).

81 Ruiz v. Court of Appeals, 363 Phil. 263, 270 [Per J. Purisima, Third Division].

82 Ponencia, p. 11.

83 Id. at 11-12.

84 Id. at 12.

85 Ziaul Haque. The Nature Of Riba Al-Nasi'a And Riba Al-Fadl. 21 ISLAMIC STUDIES 19, 19-20 (1982)., available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/20847217 (accessed May 29, 2023).

86 Id.

87 See J. Leonen, Dissenting Opinion in Re: Letter of Valenciano, Holding of Religious Rituals at the Hall of Justice Bldg. in Q.C., 806 Phil. 822 (2017) [Per J. Mendoza, En Banc].

88 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 2(a).

89 SEYYED HOSSEIN NASR, THE STUDY QURAN: A NEW TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARY 240.

90 Muhammad Samiullah. Prohibition Of Riba (Interest) & Insurance In The Light Of Islam. 21 ISLAMIC STUDIES 53, 53-54 (1982), available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/20847200 (accessed May 29, 2023).

91 Ponencia, p. 14.

92 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 4.

93 Republic Act No. 11054, art. X, sec. 1. See also Republic Act No. 11054, art. X, secs. 5, 6, and 7.

94 Presidential Decree No. 1083, art. 13, par. 1.

95 Republic Act No. 11054, art. X, sec. 5(b).

96 See also Villagracia v. Fifth Shari'a District Court, 734 Phil. 239, 255-256 (2014) [Per J. Leonen, Third Division], which provides:

"[T]here are instances when provisions in the Muslim Code apply to non-Muslims. Under Article 13 of the Muslim Code, provisions of the Code on marriage and divorce apply to the female party in a marriage solemnized according to Muslim law, even if the female is non-Muslim. Under Article 93, paragraph (c) of the Muslim Code, a person of a different religion is disqualified from inheriting from a Muslim decedent. However, by operation of law and regardless of Muslim law to the contrary, the decedent's parent or spouse who is a non-Muslim 'shall be entitled to one-third of what he or she would have received without such disqualification.' In these instances, non-Muslims may participate in Shari'a court proceedings." (Citations omitted.)

97 Republic Act No. 11054, art. XVIII, sec. 4(d).

98 Republic Act No. 11054, art. X, sec. 5.

99 Republic Act No. 11054, art. X, sec. 6.

The Lawphil Project - Arellano Law Foundation