G.R. No. 230642, September 10, 2019,

♦ Decision,

J. Reyes, Jr., [J]

♦ Separate Concurring Opinion,

Perlas-Bernabe, [J]

♦ Separate Concurring & Dissenting Opinion,

Leonen, [J]

♦ Concurring & Dissenting Opinion,

Jardeleza, [J]

♦ Separate Concurring Opinion,

Caguioa, [J]

♦ Concurring Opinion,

A. Reyes, Jr., [J]

♦ Separate Concurring & Dissenting Opinion,

Gesmundo, [J]

♦ Concurring & Dissenting Opinion,

Lazaro-Javier, [J]

[ G.R. No. 230642, September 10, 2019 ]

OSCAR B. PIMENTEL, ERROL B. COMAFAY, JR., RENE B. GOROSPE, EDWIN R. SANDOVAL, VICTORIA B. LOANZON, ELGIN MICHAEL C. PEREZ, ARNOLD E. CACHO, AL CONRAD B. ESPALDON, ED VINCENT S. ALBANO, LEIGHTON R. SIAZON, ARIANNE C. ARTUGUE, CLARABEL ANNE R. LACSINA, KRISTINE JANE R. LIU, ALYANNA MARL C. BUENVIAJE, IANA PATRICIA DULA T. NICOLAS, IRENE A. TOLENTINO AND AUREA I. GRUYAL, PETITIONERS, VS. LEGAL EDUCATION BOARD, AS REPRESENTED BY ITS CHAIRPERSON, HON. EMERSON B. AQUENDE, AND LEB MEMBER HON. ZENAIDA N. ELEPAÑO, RESPONDENTS;

ATTYS. ANTHONY D. BENGZON, FERDINAND M. NEGRE, MICHAEL Z. UNTALAN; JONATHAN Q. PEREZ, SAMANTHA WESLEY K. ROSALES, ERIKA M. ALFONSO, KRYS VALEN O. MARTINEZ, RYAN CEAZAR P. ROMANO, AND KENNETH C. VARONA, RESPONDENTS-IN-INTERVENTION;

APRIL D. CABALLERO, JEREY C. CASTARDO, MC WELLROE P. BRINGAS, RHUFFY D. FEDERE, CONRAD THEODORE A. MATUTINO AND NUMEROUS OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, ST. THOMAS MORE SCHOOL OF LAW AND BUSINESS, INC., REPRESENTED BY ITS PRESIDENT RODOLFO C. RAPISTA, FOR HIMSELF AND AS FOUNDER, DEAN AND PROFESSOR, OF THE COLLEGE OF LAW, JUDY MARIE RAPISTA-TAN, LYNNART WALFORD A. TAN, IAN M. ENTERINA, NEIL JOHN VILLARICO AS LAW PROFESSORS AND AS CONCERNED CITIZENS, PETITIONERS-INTERVENORS;

[G.R. No. 242954]

FRANCIS JOSE LEAN L. ABAYATA,GRETCHEN M. VASQUEZ, SHEENAH S. ILUSTRISMO, RALPH LOUIE SALAÑO, AIREEN MONICA B. GUZMAN, DELFINO ODIAS, DARYL DELA CRUZ, CLAIRE SUICO, AIVIE S. PESCADERO, NIÑA CHRISTINE DELA PAZ, SHEMARK K. QUENIAHAN, AL JAY T. MEJOS, ROCELLYN L. DAÑO,* MICHAEL ADOLFO, RONALD A. ATIG, LYNNETTE C. LUMAYAG, MARY CHRIS LAGERA, TIMOTHY B. FRANCISCO, SHEILA MARIE C. DANDAN, MADELINE C. DELA PEÑA, DARLIN R. VILLAMOR, LORENZANA L. LLORICO, AND JAN IVAN M. SANTAMARIA, PETITIONERS, VS. HON. SALVADOR MEDIALDEA, EXECUTIVE SECRETARY, AND LEGAL EDUCATION BOARD, HEREIN REPRESENTED BY ITS CHAIRPERSON, EMERSON B. AQUENDE, RESPONDENTS.

CONCURRING and DISSENTING OPINION

LAZARO-JAVIER, J.:

We all have different competencies. Some of us are

intellectually gifted, some of us athletically gifted, some of us

are great listeners. Everyone has a different level of what they

can do.1

Don't take on things you don't believe in and that you yourself

are not good at. Learn to say no. Effective leaders match the

objective needs of their company with the subjective

competencies. As a result, they get an enormous amount of

things done fast.2

PREFATORY

The pursuit of excellence has never been a bad thing. From our ranks, we shower accolades to the best, brightest, most efficient, most innovative - the cut above the rest. Soon, the Court will again be recognizing excellence of execution among our judges and clerks of court, conferring on them the judicial excellence awards. These awards do not come cheap. They are laden with perks and advantages that are sorely denied others. Yet this is not discrimination. The differential treatment is not based on something like the color of one's skin or the circumstances regarding one's birth-the differential treatment arises not from an unchanging and unchangeable characteristics and traits, but from circumstances largely within the awardees' control and efforts. Exclusion necessarily comes with quality.

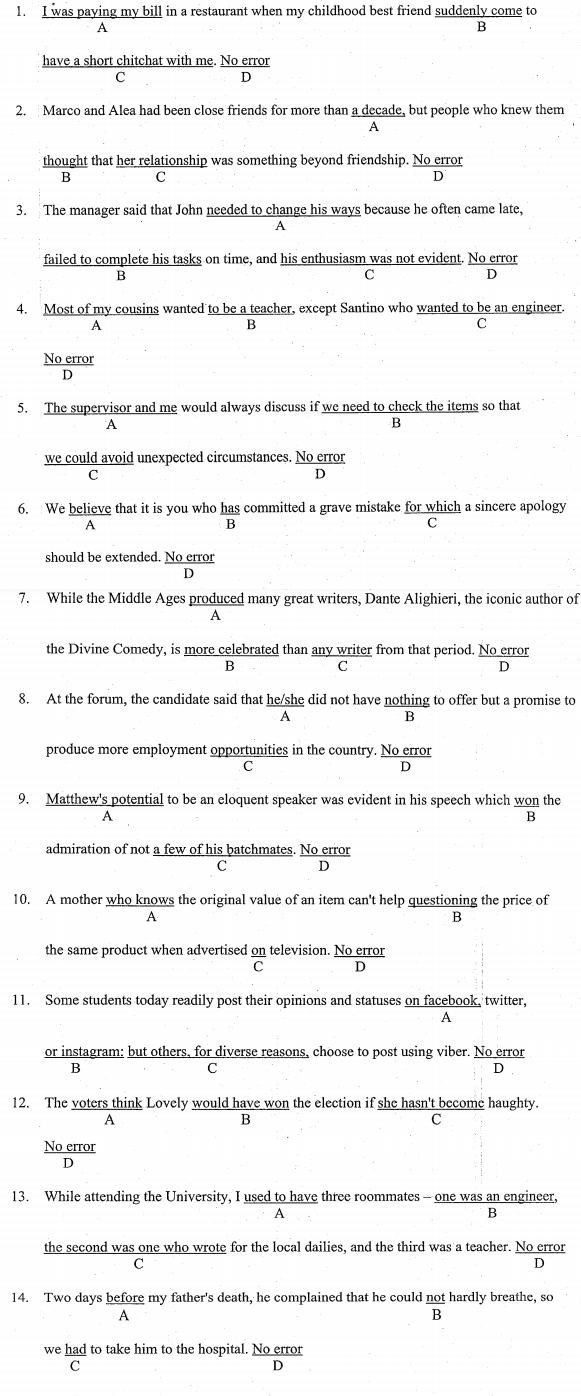

To strive for excellence and to require others to also trail this path in matters of privilege is not usurping that other's role in this regard. This is the case where the requirer of excellence shares the same goal of excellence as the required. More in point to the present cases, who would not want something more from a law student whose answer to the following question is as follows -

Teacher: Q - What are fruits as they relate to our study of Obligations & Contracts?

Student - "The Obligations and contracts is very beneficial to our life. The fruit I relate is Banana. This fruit have a vitamins and it gave the beneficial like became taller."3

Each of us has distinct competencies. Some run quicker than others. A few love to ruminate. There are fifteen (15) Justices in the Court, and in a room full of lawyers and judges, this is as exclusive as it can get. Of the several hundreds who take the Bar, not everyone gets over the hurdle. In any World Cup, there are only a number of aspirants. The top-tier law schools cannot accommodate a slew of the applicants. It is not society's fault that not every Army officer comes from the Philippine Military Academy, or a lawyer can claim blue, maroon, red, yellow, or green as the color of his or her scholastic pedigree. The right of each citizen to select a course of study is subject to fair, reasonable, and equitable admission and academic requirements.

If we are agreed that quality and excellence and their resulting exclusionary effect are valid objectives in any institution of higher learning like law schools, we next ask, who decides whom to accept in such institutions, like law schools? We should also be concerned with things like curriculum, faculty; internal administration, library, laboratory class and other facilities.4 This is because when we speak of quality education we have in mind such matters, among others, as curriculum development, development of learning resources and instructional materials, upgrading of library and laboratory facilities, innovations in educational technology and teaching methodologies, improvement of research quality, and others.5 Who speaks for these requisites?

ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK

To resolve the cases here, it is important to understand the relationship of the intersecting constitutional rights and interests as visually reflected below:

State: shall exercise reasonable supervision and regulation of all educational institutions; protect and promote the right of all citizens to quality education at all levels and shall take appropriate steps to make such education accessible to all.

Institutions of Higher Learning: academic freedom shall be enjoyed in all institutions of higher learning. Citizens: right to select a profession or course of study, subject to fair, reasonable, and equitable admission and academic requirements.

Not one of these rights and interests is superior to any of the others. Each has an impact on any of the others in terms of meaning and application. It is the Court's duty to weigh and balance these rights and interests according to the circumstances of each case.

In the exercise of the State's power to reasonably supervise and regulate all educational institutions, the State is mandated to protect and promote not just any access to education but access to quality education. So the State is expected to initiate, innovate, and implement measures to achieve this objective.

It is established that "the duty of providing quality education entails the duty of screening those who seek education. Necessarily too, the talent that is required in order to merit quality education goes up as one goes higher in the educational ladder of progression. . . . As already seen, however, there is also recognition of the right of the school to impose admission standards. The State itself may also set admission standards."6

Which of the State agencies is responsible for this task? The Court has already recognized that -

. . . . the Constitution indeed mandates the State to provide quality education, the determination of what constitutes quality education is best left with the political departments who have the necessary knowledge, expertise, and resources to determine the same. The deliberations of the Constitutional Commission again are very instructive:

Now, Madam President, we have added the word "quality" before "education" to send appropriate signals to the government that, in the exercise of its supervisory and regulatory powers, it should first set satisfactory minimum requirements in all areas: curriculum, faculty, internal administration, library, laboratory class and other facilities, et cetera, and it should see to it that satisfactory minimum requirements are met by all educational institutions, both public and private. When we speak of quality education we have in mind such matters, among others, as curriculum development, development of learning resources and instructional materials, upgrading of library and laboratory facilities, innovations in educational technology and teaching methodologies, improvement of research quality, and others.

Here and in many other provisions on education, the principal focus of attention and concern is the students. I would like to say that in my view there is a slogan when we speak of quality of education that I feel we should be aware of, which is, "Better than ever is not enough." In other words, even if the quality of education is good now, we should attempt to keep on improving it.7 (emphasis added)

A citizen - not any individual but a citizen - has the right to select a profession or a course of study leading to that chosen profession; however, the citizen is not guaranteed admission to the profession or to the course of study and school of his or her choosing. The right given to every citizen is to select - a profession or course of study. BUT this right does not necessarily give rise to and guarantee a right to pursue, and engage in, the chosen profession of the citizen or a right to be admitted to the course of study and school of the citizen's choosing. The citizen must have to consider the State's duty to regulate and supervise reasonably educational institutions, which would have to include measures to assure the citizen's access to quality education, as well as the express limitation inherent in every citizen's right to select a profession or course of study, i.e. - - - fair, reasonable, and equitable admission and academic requirements.

As the intersecting rights and interests show, the State has a stake in the determination and imposition of the fair, reasonable, and equitable admission and academic requirements through the duty of the political departments of the State to reasonably regulate and supervise educational institutions towards, among others, assuring the citizen of access to quality education.

In addition, the Constitution also recognizes the important role that academic freedom plays in providing quality education. Institutions of higher learning including law schools enjoy academic freedom in the highest legal order possible. Written in jurisprudence are the substance and parameters of this constitutional privilege and duty which entitles its holders to determine for itself on academic grounds who may teach, what may be taught, how it shall be taught, and who may be admitted to study. Subsumed under this entitlement is the capacity of institutions of higher learning to determine and impose fair, reasonable, and equitable admission and academic requirements.

Both the State through its political departments and the institutions of higher learning have roles to play in providing our citizens access to quality education. It is our duty to balance the academic freedom of institutions of higher learning and the State's exercise of reasonable supervision and regulation. Academic freedom is not absolute.

The foregoing rights and interests of the State, the citizen, and the institutions of higher learning interplay in the present cases. These rights and interests very strongly suggest that these cases are not and have never been about a willy-nilly and free-wheeling intellectual inquiry of individuals on the nature of the law or its relevance to everyday life and its application to real life situations, or about those individuals whose only interest in obtaining legal education is to get qualified for some higher civil service postings.

Individuals are not forbidden from learning the law for whatever motives or purposes they may each have. Every individual has the freedom of intellectual and non-intellectual inquiry, a cognate of each one's freedom of thought, expression, and speech that is not in any way restricted by the discussion and ruling which follows.

It is important that we see through the distinction between intellectual inquiry within the narrow confines of educational institutions like law schools and a citizen's political right of free expression. In this light, academic freedom and the State's power of reasonable supervision and regulation of all educational institutions bear upon the context of the narrower academic community.8 This is different from an individual's freedom of expression which encompasses his or her freedom of intellectual inquiry for whatever purposes it may serve him or her.

For clarity and emphasis, what we are dealing with here is different from merely wanting to study law for its own sake or for immediate career advancement which a law degree carries in the civil service. Our endeavour here is a distinct proposition that has a life of its own. In the words of the Court in Garcia v. Faculty Admissions Committee,9 "[i]t is equally difficult to yield conformity to the approach taken that colleges and universities should be looked upon as public utilities devoid of any discretion as to whom to admit or reject. Education, especially higher education, belongs to a different, and certainly, higher category."

Here, the issues are defined by the education of and learning by citizens within the confines of an educational institution whose existence and operation are imbued with public concern, to pursue a course of study subject to reasonable regulation and supervision by both the State and the law school, as to access, quality and admission, and academic requirements, where the citizen if successful gets entitled to qualify for and engage in a profession that we all admit to be noble and suffused with public interest.

I understand that some eager students would have their dreams of becoming law students scuttled. To this situation, I have only to stress the advice reflected in my chosen epigraphs above -

We all have different competencies. Some of us are intellectually gifted, some of us athletically gifted, some of us are great listeners. Everyone has a different level of what they can do.

Don't take on things you don't believe in and that you yourself are not good at. Learn to say no. Effective leaders match the objective needs of their company with the subjective competencies. As a result, they get an enormous amount of things done fast.

In the context of the Philippine Law School Admission Test (PhiLSAT), whose validity as a screening mechanism I stand by as my resolution to this Opinion's second issue. Indeed, nothing can be more liberating than taking the epigraphs to heart and to bear on one's aspirations in life.

Our task is to consider carefully, weigh and balance the rights and interests of these stakeholders. Each is equally important, compelling, and relevant as the next right and interest. Not one is superior to another, though one may qualify the other. When considered, weighed, and balanced properly, these rights and interests will form the tapestry against which we will be able to judge the validity of the assailed statutory provisions and the relevant founding regulation. I now endeavour to do this and more.

THOUGHTFUL RUMINATIONS

First. I have been confronted with the idea that as regards education in institutions of higher learning, the State's supervisory and regulatory power is only an auxiliary power in relation to educational institutions, be it basic, secondary, or higher education. It has been said that this must be necessarily so because the right and duty to educate, being part and parcel of youth-rearing, does not inure to the State at the first instance. Rather, it belongs essentially and naturally to the parents who surrender it by delegation to the educational institutions.

I beg to differ. It is well-taken if this idea were referring only to preschool or elementary school students. But the cases here are not about the education of young and impressionable children. They are about the education which molds an individual into a legal professional, the one whom another would meet to seek help about his or her life, liberty, or property. Nor are the cases here about nurturing generally socially acceptable values.

They are about piecing together building blocks to develop focused core values essential to professions, including the legal profession. With respect to the latter, regardless of how a potential student of law has been reared by his or her or its natural or surrogate parents, he or she must learn focused core values that the confluence of private and public communities relevant to the legal profession has judged to be important. In fact, some of these focused core values may be different from the basic values which the potential student of law may have been taught at home.

For example:

| Home Values |

Lawyer's Values |

| 1. Be Honest |

1. Duty of Confidentiality |

| 2. Defend Only The Good Ones |

2. Right to Counsel and Duty of Loyalty to Client |

| 3. Love and Defend Your Family |

3. Avoid Conflict of Interest in the Performance of Lawyer's Duties |

To stress, the duty of providing quality education entails the duty of screening those who seek education. Necessarily too, the talent that is required in order to merit quality education goes up as one goes higher in the educational ladder of progression . . . ."10

The State's supervisory and regulatory power in relation to prescribing the minimum admission requirements has been said to be a component of police power, which as explained in Tablarin v. Gutierrez,11 "is the pervasive and non-waivable power and authority of the sovereign to secure and promote all the important interests and needs - in a word, the public order - of the general community." Hence, the State's supervisory and regulatory power over institutions of higher learning cannot be characterized as a mere auxiliary power in the ordinary sense of being just a spare, substitute, or supplementary power.

Second. There are three (3) issues to be resolved here:

1. Which State agent - the Supreme Court or the Legal Education Board or both - is responsible for exercising reasonable regulation and supervision of all educational institutions? In this regard, is the reasonable regulation and supervision of legal education within the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court? If it is, what is the exact jurisdiction of the Supreme Court over the reasonable regulation and supervision of legal education? May this jurisdiction be assigned or delegated to or shared with the Legal Education Board created under RA 7662?

2. Do Subsection 7(e) of RA 766212 and Legal Education Board Memorandum Order No. 7, series of 2016, (LEBMO No. 7) fall within the constitutionally-permissible supervision and regulation?

3. Are Subsections 7(g) and (h) of RA 766213 ultra vires for encroaching into the constitutional powers of the Supreme Court.

Let me address these issues sequentially.

1. Which State agent - the Supreme Court or Congress and the Legal Education Board or both - is responsible for exercising reasonable regulation and supervision of all educational institutions? In this regard, is the reasonable regulation and supervision of legal education within the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court? If it is, what is the exact jurisdiction of the Supreme Court over the reasonable regulation and supervision of legal education? May this jurisdiction be assigned or delegated to or shared with Congress and the Legal Education Board created under RA 7662?

I accept the Decision's ruling that Congress and the Legal Education Board have primary and direct jurisdiction to exercise reasonable supervision and regulation of legal education and the law schools providing them. The Supreme Court has no primary and direct jurisdiction over legal education and law schools.

The Supreme Court, however, is not entirely irrelevant when it comes to legal education. Although the primary and direct responsibility rests with Congress and the Legal Education Board to reasonably supervise and regulate legal education and law schools, the Supreme Court can and will intervene when a justiciable controversy hounds the discharge of the Legal Education Board's duties. The Supreme Court will also have to intervene when its power to administer admission to the Bar is infringed. Admission to law school is far different from admission to the Bar. As the Decision has aptly discussed, historically, textually, practicably, and legally, there has been no demonstrable assignment of the function to supervise and regulate legal education to the Supreme Court.

Textual. The confusion regarding the Supreme Court's supervisory and regulatory role stems from Subsection 5(5) of Article VIII of the Constitution which enunciates the power of the Supreme Court to promulgate rules concerning the admission to the practice of law.

Admission to the practice of law, however, is not the same as law school admission, which is part and parcel of legal education regulation and supervision. The former presupposes the completion of a law degree and the submission of an application for the Bar examinations, among others. In terms of proximity to membership in the Bar, admission to the practice of law is already far deep into the process, the outcome of legal education plus compliance with so many more criteria.14 On the other hand, law admission signals only the start of the long and arduous process of legal education. It is therefore speculative and somehow presumptuous to consider an applicant for law admission as already a candidate for admission to the practice of law.

Clearly, Subsection 5(5) of Article VIII cannot be the source of power of the Supreme Court to exercise reasonable supervision and regulation of legal education and law schools as a primary and direct jurisdiction.

Historical. The Supreme Court has not played a primary and direct role in regulating and supervising legal education and law schools. Legal education and law schools have been consistently placed for supervision and regulation under the jurisdiction of the legislature, and in turn, the country's education departments.

For instance, it was the University of the Philippines College of Law which pioneered the legal education curriculum in the Philippines. On the basis of statutory authority, the Bureau of Private Schools acted as supervisor of law schools and national coordinator of law deans. Thereafter, the Bureau of Higher Education regulated law schools. Still further later, DECS Order No. 27-1989, series of 1989 outlined the policies and standards for legal education, qualifications, and functions of a law dean, and qualifications, compensation and conditions of employment of law faculty, formulated a law curriculum, and imposed law admission standards.

Impracticable. The Supreme Court has no office and staff dedicated to the task of supervising and regulating legal education and law schools. It also has no expertise as educators of these tertiary students. It has no budget item for this purpose.

Legal. Section 12 of Article VIII of the Constitution15 prohibits members of the Supreme Court from being designated to any agency (which includes functions) performing quasi-judicial or administrative functions. The spirit of this prohibition precludes the Court from exercising reasonable supervision and regulation of legal education and law schools. The reason is that this task involves administrative functions - "those which involve the regulation and control over the conduct and affairs of individuals for their own welfare and the promulgation of rules and regulations to better carry out the policy of the legislature or such as are devolved upon the administrative agency by the organic law of its existence."16

Manila Electric Co. v. Pasay Transportation Co.17 has emphasized that the Supreme Court should only exercise judicial power and should not assume any duty which does not pertain to the administering of judicial functions. In that case, a petition was filed requesting the members of the Supreme Court, sitting as a board of arbitrators, to fix the terms and the compensation to be paid to Manila Electric Company for the use of right of way. The Court held that it would be improper and illegal for the members of the Supreme Court, sitting as a board of arbitrators, whose decision shall be final, to act on the petition of Manila Electric Company. The Court explained:

We run counter to this dilemma. Either the members of the Supreme Court, sitting as a board of arbitrators, exercise judicial functions, or as members of the Supreme Court, sitting as a board of arbitrators, exercise administrative or quasi judicial functions. The first case would appear not to fall within the jurisdiction granted the Supreme Court. Even conceding that it does, it would presuppose the right to bring the matter in dispute before the courts, for any other construction would tend to oust the courts of jurisdiction and render the award a nullity. But if this be the proper construction, we would then have the anomaly of a decision by the members of the Supreme Court, sitting as a board of arbitrators, taken therefrom to the courts and eventually coming before the Supreme Court, where the Supreme Court would review the decision of its members acting as arbitrators. Or in the second case, if the functions performed by the members of the Supreme Court, sitting as a board of arbitrators, be considered as administrative or quasi judicial in nature, that would result in the performance of duties which the members of the Supreme Court could not lawfully take it upon themselves to perform. The present petition also furnishes an apt illustration of another anomaly, for we find the Supreme Court as a court asked to determine if the members of the court may be constituted a board of arbitrators, which is not a court at all.

The Supreme Court of the Philippine Islands represents one of the three divisions of power in our government. It is judicial power and judicial power only which is exercised by the Supreme Court. Just as the Supreme Court, as the guardian of constitutional rights, should not sanction usurpations by any other department of the government, so should it as strictly confine its own sphere of influence to the powers expressly or by implication conferred on it by the Organic Act. The Supreme Court and its members should not and cannot be required to exercise any power or to perform any trust or to assume any duty not pertaining to or connected with the administering of judicial functions. (emphasis added)

Imposing regulatory and supervisory functions upon the members of the Court constitutes judicial overreach by usurping and performing executive functions. In resolving the first issue, we are duty bound not to overstep the Court's boundaries by taking over the functions of an administrative agency. We should abstain from exercising any function which is not strictly judicial in character and is not clearly conferred on the Court by the Constitution.18 To stress, "the Supreme Court of the Philippines and its members should not and cannot be required to exercise any power or to perform any trust or to assume any duty not pertaining to or connected with the administration of judicial functions."19

2. Do Subsection 7(e) of RA 7662 and Legal Education Board Memorandum Order No. 7, series of 2016 (LEBMO No. 7) fall within the constitutionally permissible supervision and regulation?

I submit that both Subsection 7(e) of RA7662 and LEBMO No. 7, series of 2016, as a minimum standard for admission to a law school, fall within the constitutionally-permissible reasonable supervision and regulation by the State over all educational institutions.

Subsection 7(e) of RA 7662 states "[f]or the purpose of achieving the objectives of this Act, the Board shall have the following powers and functions . . . (e) to prescribe minimum standards for law admission and minimum qualifications and compensation of faculty members . . . ."

On the other hand, LEBMO No. 7 imposes as an admission requirement to a law school passing (defined as obtaining a 55% cut-off score20) the "one-day aptitude test that can measure the academic potential of the examinee to pursue the study of law [by testing] communications and language proficiency, critical thinking skills, and verbal and quantitative reasoning."21 This one-day test is the Philippine Law School Admission Test (PhiLSAT).

PhiLSAT is offered at least once a year,22 recently, twice a year, and an applicant can take PhiLSAT as many times as one would want if unsuccessful in the attempt.23 A law school may prescribe admission requirements, but these must be in addition to passing the PhiLSAT.24

There is no doubt that Subsection 7(e) of RA7662 and LEBMO No. 7 are measures to regulate and supervise law schools. The issue: are these measures reasonable?

I appreciate the Decision's ruling that the State can. conduct the PhiLSAT. But I do not agree with its ruling that passing the PhiLSAT cannot be a minimum requirement for admission to a law school. This is a ruling that takes with its left hand, what it gives with the right. After stating that PhiLSAT is within the State's reasonable supervisory and regulatory power to design and provide or conduct as a minimum standard for admission to a law school, the Decision then disempowers the State of such power and authority, when it gave discretion to the law schools to ignore PhiLSAT completely.

The Decision accepts that PhiLSAT is a minimum standard for law school admission and is therefore valid under the State's power to regulate and supervise education in a reasonable manner. Since PhiLSAT is valid, though it may infringe a portion of a law school's academic freedom, then it cannot be set aside. It is a contradiction in terms to say that PhiLSAT is a valid regulation but that it can be ignored.

Reasonableness is the standard endorsed by the Constitution. Reasonableness requires deference. It is the stark opposite of the search for the correct measure of regulation and supervision, which means there can only be one proper means of regulating and supervising educational institutions. Where the power, however, refers to the exercise of reasonable regulation or supervision, a reviewing court cannot substitute its own appreciation of the appropriate solution; rather it must determine if the outcome falls within a range of possible, acceptable outcomes which are defensible in respect of the facts and law.25

Where the standard is reasonableness, there could be more than one solution, so long as each of them is reasonable. If the process and the solution fit comfortably with the principles of justification (i.e., existence of a rational basis for the action), transparency, and intelligibility (i.e., the adequacy of the explanation of that rational basis), it is not open to a reviewing court to substitute its own view of the preferable solution.

Conversely, where a regulation or supervision is determined to be unreasonable, it means that while there could have been many appropriate measures to regulate or supervise, the particular regulation or supervision which was adopted is not reasonable.

The existence of justification or whether there exists a rational basis to support the regulation, lies at the core of the definition of reasonableness. The test of justification is a test of proportionality.26 Accordingly:

First, the objective of the regulation must be pressing and substantial, in order to justify a limit on a right. This is a threshold requirement, which is analyzed without yet considering the scope of the infringement made by the regulation, the means employed, or the effects of the measure. The integrity of the justification analysis requires that the objective of the regulation be properly stated. The relevant objective is the very objective of the infringing measure, not the objective of the broader provision upon which the regulation hinges.

Second, the means by which the objective is furthered must be proportionate. The proportionality inquiry comprises three (3) components: (i) rational connection to the objective, (ii) minimal impairment of the right, and (iii) proportionality between the effects of the measure (a balancing of its salutary and deleterious effects) and the stated objective of the regulation. The proportionality inquiry is both normative and contextual, and requires that a court balances the interests of society with the interests of individuals and groups.

The question at the first step of the proportionality inquiry is whether the measure that has been adopted is rationally connected to this objective. This can be proved by evidence of the harm that the regulation is meant to address. In cases where such a causal connection is not scientifically measurable, the rational connection can be made out on the basis of reason or logic.

The second component of the proportionality test requires evidence that the regulation at issue impairs the right as little as reasonably possible. This can be shown by what the regulation seeks to achieve, what the effects of the regulation could be (i.e., if they are overinclusive or underinclusive) or how the regulation is tailored to respond to a specific problem.

At the final stage of the proportionality analysis, it must be asked whether there is proportionality between the overall effects of the infringing regulation and the objective. This involves weighing the salutary effects of the objectives and the deleterious effects of the regulation. Are the benefits of the impugned regulation illusory and speculative? Or are these benefits real? Is it clear how the objectives are enhanced by the regulation? Are the deleterious effects on affected rights holders serious? What are these deleterious effects? What is the harm inflicted on these rights holders?

Let me deal first with Subsection 7(e) of RA 7662.

Existence of Justification. Subsection 7(e) of RA 7662 states:

(e) to prescribe minimum standards for law admission and minimum qualifications and compensation of faculty members . . . .

The State objectives in the enactment of Subsection 7(e) of RA 7662 are found in Sections 2 and 3 of the same statute:

Section 2. Declaration of Policies. - It is hereby declared the policy of the State to uplift the standards of legal education in order to prepare law students for advocacy, counselling, problem-solving, and decision-making, to infuse in them the ethics of the legal profession; to impress on them the importance, nobility and dignity of the legal profession as an equal and indispensable partner of the Bench in the administration of justice and to develop social competence. Towards this end, the State shall undertake appropriate reforms in the legal education system, require proper selection of law students, maintain quality among law schools, and require legal apprenticeship and continuing legal education.

Section 3. General and Specific Objective of Legal Education. - (a) Legal education in the Philippines is geared to attain the following objectives:

(1) to prepare students for the practice of law;

(2) to increase awareness among members of the legal profession of the needs of the poor, deprived and oppressed sectors of society;

(3) to train persons for leadership;

(4) to contribute towards the promotion and advancement of justice and the improvement of its administration, the legal system and legal institutions in the light of the historical and contemporary development of law in the Philippines and in other countries.

(b) Legal education shall aim to accomplish the following specific objectives:

(1) to impart among law students a broad knowledge of law and its various fields and of legal institutions;

(2) to enhance their legal research abilities to enable them to analyze, articulate and apply the law effectively, as well as to allow them to have a holistic approach to legal problems and issues;

(3) to prepare law students for advocacy, counselling, problem-solving and decision-making, and to develop their ability to deal with recognized legal problems of the present and the future;

(4) to develop competence in any field of law as is necessary for gainful employment or sufficient as a foundation for future training beyond the basic professional degree, and to develop in them the desire and capacity for continuing study and self-improvement;

(5) to inculcate in them the ethics and responsibilities of the legal profession; and

(6) to produce lawyers who conscientiously pursue the lofty goals of their profession and to fully adhere to its ethical norms. (emphasis added)

The objectives of Subsection 7(e) of RA 7662 are pressing and substantial. This is because they arise from, or at least relate to, the objective of achieving quality of education (including of course legal education), which the Constitution has seen proper to elevate as a normative obligation.

The foregoing objectives justify a limitation on a citizen's right to select a profession and course of study because they fall under the express limit to this right, "subject to fair, reasonable, and equitable admission and academic requirements. " As well, the oversearching power of the State to exercise reasonable supervision and regulation of all educational institutions justifies this qualification. The objectives also justify a limitation on the academic freedom of every law school as an institution of higher learning because quality legal education is a constitutional obligation of the State to protect and promote.

In real terms, why would we not want law students who have the basic abilities to communicate clearly and concisely, analyze fact situations and the legal rules that apply to them, and understand the texts assigned to them for reading and discussion? Why should we be content with just legal education when the Constitution no less and our practical wisdom demand that we conjoin education with quality?

As the assailed measures prescribe mere minimum standards for law admission and minimum qualifications and compensation of faculty members, Subsection 7(e) of RA7662 and LEBMO No. 7 are proportionate to the foregoing objectives.

Minimum law admission and minimum faculty competence and compensation requirements are rationally connected to quality legal education and to each of the objectives mentioned in sections 2 and 3 above quoted. This rational connection is intuitive, logical, and common-sensical. Prescribing these minimum standards can lead to and accomplish the objectives of Subsection 7(e) as they favorably affect the quality of students that a law school admits as well as the quality of law faculty who in turn mentors the students whose aptitude for law studies has been tested. In the words of Professor Bernas, paraphrasing the Constitutional Commission:

. . . . the duty of providing quality education entails the duty of screening those who seek education. Necessarily too, the talent that is required in order to merit quality education goes up as one goes higher in the educational ladder of progression . . . . However, as already seen, there is also recognition of the right of school to impose admission standards. The state itself may also set admission standards.27

Subsection 7(e) impairs the right of a citizen to select a profession and a course of study and the academic freedom of every law school only as little as reasonably possible. For Subsection 7(e) prescribes only minimum standards of law admission and faculty competence and compensation.

This provision is not overinclusive or underinclusive as the minimum standards do not impact on aspects of a citizen's right to select a profession or course of study or the academic freedom of a law school other than the admission of students into a law degree program of a law school.

Subsection 7(e) is tailor-fit to the objective of fostering law student success in law school and ensuring competent law faculty to teach these students.

It is reasonable to assume that every self-respecting law school would see Subsection 7(e)'s requirements of minimum standards for law admission and faculty compensation and competence as necessary ingredients of quality legal education, and that these minimum requisites would coincide with each law school's good practices in administering legal education.

At the final stage of the proportionality analysis, there is proportionality between the overall salutary effects of the objectives of Subsection 7(e) and the deleterious impact of prescribing minimum standards for admission of students in law schools and minimum qualifications and compensation for the law faculty.

The benefits obtained from achieving the objectives are obvious. No one can argue against students who are academically competent and have a personality ready for the rigors of legal education. It will spare both the law student and the law school of the waste of time, expense, and trauma of not being able to fit in and succeed. Minimum standards for law admission and law faculty competence and compensation are base-line predictors of success in law school and quality of the legal education it offers. Professor Bernas and the Constitutional Commission, as quoted above, shared this observation.28

On the other hand, the deleterious effect of the imposition of such minimum standards is speculative

In the first place, petitioners offered no evidence of the oppressive or discriminatory nature and other evils that could be attributed to the prescription of such minimum standards. In fact, the converse is true - easily more than half of the applicants passed the first versions of PhiLSAT.

| YEAR, MONTH |

PASSING RATE |

| 2017, April |

0.8143 |

| 2017, September |

0.5776 |

| 2018, April |

0.6139 |

| 2018, September |

0.5678 |

| 2019, April |

Unreleased29 |

Accepting that quality legal education is a pressing and substantial objective, the screening of law students and the provision of minimum levels of competency and compensation standards for law faculty are logical necessary steps towards achieving this objective.

Existence of Transparency and Intelligibility. It cannot be denied that Subsection 7(e) of RA 7662 was adopted by Congress after deliberations. These deliberations articulate the reasons behind the enactment of Subsection 7(e). The policy declaration and the list of objectives mentioned in RA 7662 also adequately explain the basis for Subsection 7(e).

Action as being within a range of possible, acceptable, and defensible outcomes. The Congress enacted Subsection 7 (e) as one of several measures to achieve the constitutional objective of quality education, which includes quality legal education. Prescribing minimum enforceable standards upon the admission of law students and the compensation and qualifications of law faculty is one of these courses of action. Actually, it is difficult to imagine how the narrative of quality legal education could not lead to the imposition of standards referred to in Subsection 7(e). This intuitive justification for these measures was not lost on the Constitutional Commission who believed that the duty to provide and promote quality education demanded the screening of students for base-line competencies:

[T]he duty of providing quality education entails the duty of screening those who seek education. Necessarily too, the talent that is required in order to merit quality education goes up as one goes higher in the educational ladder of progression . . . . However, as already seen, there is also recognition of the right of school to impose admission standards. The state itself may also set admission standards.30

I now apply the proportionality test to determine the reasonableness of LEBMO No. 7.

LEBMO No. 7, series of 2016, governs not only the mechanics but also the regulatory and supervisory aspects of PhiLSAT.

Like Subsection 7(e) of RA 7662, the general objective of PhiLSAT is to improve the quality of legal education. LEBMO No. 7's particular objective is to measure the academic potential of an examinee to pursue the study of law.

The means to these objectives is PhiLSAT's one-day testing of communications and language proficiency, critical thinking skills, and verbal and quantitative reasoning.

To enforce compliance, admission to a law degree program and a law school requires or is dependent upon obtaining the cut-off score of 55°/o correct answers in PhiLSAT.

As stated, PhiLSAT is offered at least once a year,31 recently, twice a year, and an applicant can take PhiLSAT as many times as one would want if unsuccessful in any of the attempts.32

There is also a penalty for non-compliance by a law school, that is, if it admits students flunking the PhiLSAT.33

Law schools may impose other admission requirements such as but not limited to a score higher than 55% from an examinee.

I have already established above that protecting and promoting quality legal education (including legal education) as an objective is pressing and substantial.

Part and parcel of the objective of quality legal education is the objective of being able to screen students for the purpose of ascertaining their academic competencies and personal readiness to pursue legal education. As quoted above:

[T]he duty of providing quality education entails the duty of screening those who seek education. Necessarily too, the talent that is required in order to merit quality education goes up as one goes higher in the educational ladder of progression . . . . However, as already seen, there is also recognition of the right of school to impose admission standards. The state itself may also set admission standards.34

PhiLSAT as devised is proportionate to PhiLSAT's objectives. The following proportionality inquiry proves this conclusion.

PhiLSAT is rationally connected to quality legal education and the measurement of one's academic potential to pursue the study of law. To repeat, "the duty of providing quality education entails the duty of screening those who seek education. Necessarily too, the talent that is required in order to merit quality education goes up as one goes higher in the educational ladder of progression . . . . However, as already seen, there is also recognition of the right of school to impose admission standards. The state itself may also set admission standards."35

PhiLSAT helps determine if an examinee has the basic skills to be able to complete successfully the law school coursework.ℒαwρhi৷

It is true that PhiLSAT limits both the right of a citizen to select a profession and a course of study and the academic freedom of every institution of higher learning. But it does so only as little as reasonably possible.

In the first place, the right of a citizen to select a profession and a course of study has an internal limitation. The Constitution expressly limits this right subject to fair, reasonable, and equitable admission and academic requirements. This right therefore is not absolute, and PhiLSAT as an admission requirement falls within the limitation to this right.

In fact, as it measures only the basic competencies necessary to survive the coursework in a law school, PhiLSAT enhances a law school applicant's sense of dignity and self-worth as it prevents potential unmet expectations and wastage of time, resources and efforts.

If an applicant does not obtain a score of at least 55% in this test involving the most basic of skills required in a law school, despite the unlimited chances to write PhiLSAT, then the applicant's aptitude must lie somewhere else.

Secondly, it is inconceivable to think of a university program without any admission criteria whatsoever. A self-respecting law school - a law school that abhors being referred to as a diploma mill - subscribes to some means to measure the academic and personal readiness of its students, and as a badge of honor and pride, to distinguish its students from the rest. And, if a law school can impose standards, the State can also do in accordance with its powers and duties under the Constitution.

The impact of PhiLSAT on the right of law schools as an institution of higher learning to select their respective students must be reconciled with the State's power to protect and promote quality education and to exercise reasonable supervision and regulation of all educational institutions.

Verily, the impact of PhiLSAT on academic freedom is for sure, minimal.

The analysis takes us first to Nos. 1 and 2 of LEBMO No. 7, which state the "Policy and Rationale" of the "administration of a nationwide uniform law school admission test for applicants to the basic law courses in all law schools in the country." Thus:

1. Policy and Rationale. - To improve the quality of legal education, all those seeking admission to the basic law courses leading to either a Bachelor of Laws or Juris Doctor degree shall be required to take the Philippine Law School Admission Test (PhiLSAT), a nationwide uniform admission test to be administered under the control and supervision of the [Legal Education Board].

2. Test Design. - The PhiLSAT shall be designed as a one-day aptitude test that can measure the academic potential of the examinee to pursue the study of law. It shall test communications and language proficiency, critical thinking skills, and verbal and quantitative reasoning. (emphasis added)

No. 1 of LEBMO No. 7 states the animating purpose, to improve the quality of legal education, for requiring the taking of the PhiLSAT by applicants for admission to a law school.

No. 2 of LEBMO No. 7 provides the mechanism for achieving No. 1.

Nos. 7 and 9 of LEBMO No. 7 further clarify how PhiLSAT would be used to measure the academic potential of an applicant to a law school:

7. Passing Score - The cut off or passing score for the PhilSAT shall be FIFTY-FIVE PERCENT (55%) correct answers, or such percentile score as may be prescribed by the LEB.

8. Test Results - Every examinee who passed the PhilSAT shall be issued by the testing administrator a CERTIFICATE OF LEGIBILITY (COE), which shall contains the examinees test score/rating and general average to the bachelor's degree completed. Examinees who fail to meet the cut-off or passing score shall by issued a Certificate of Grade containing his/her test score/rating. The COE shall be valid for two (2) years and shall be submitted to the admitting law school by the applicant.

9. Admission Requirement - All college graduates or graduating students applying for admission to the basic law course shall be required to pass the PhilSAT as a requirement for admission to any law School in the Philippines. Upon the affectivity of this memorandum order, no applicant shall be admitted for enrollment as a first year student in the basic law courses leading to a degree of either Bachelor of Laws or Juris Doctor unless he/she has passed the PhilSAT taken within 2 years before the start of studies for the basic law course and presents a valid COE as proof thereof. (emphasis added)

This stage of the analysis requires us to refer to Nos. 10 and 11 of LEBMO No. 7:

10. Exemption. - Honor graduates granted professional civil service professional eligibility pursuant to Presidential Decree No. 907 who are enrolling within two (2) years from their college graduation are exempted from taking and passing the PhiLSAT from for purposes of admission to the basic law course.

11. Institutional Admission Requirements. - The PhiLSAT shall be without prejudice to the right of a law school in the exercise of its academic freedom to prescribe or impose additional requirements for admission, such as but not limited to:

a. A score in the PhiLSAT higher than the cut-off or passing score set by the LEB;

b. Additional or supplemental admission tests to measure the competencies and/or personality of the applicant; and

c. Personal interview of the applicant (emphasis added)

No. 11 of LEBMO No. 7 itself expressly recognizes the right of law schools to impose screening measures in addition to the taking or writing of PhiLSAT, such as but not limited to a PhiLSAT score of higher than 55%, additional admission tests, and personal interview of the applicant.

The law school may also opt to rely solely on the result of the PhiLSAT in accepting students.

The additional requirements that a law school may impose would have to be of the same kind as a PhiLSAT score of higher than 55%, additional admission tests, or a personal interview of the applicant - the defining characteristic of the specie in the enumeration is the ability to measure the competencies and/or personality of the applicant relevant to and indicative of an applicant's success in law school - an applicant's communications or language proficiency, critical thinking skills, and verbal and quantitative reasoning, and personality fit for success in law school. So any screening module that makes such measurements could be imposed as an additional measure.

On the other hand, No. 10 of LEBMO No. 7 provides for an exemption from both writing and passing PhiLSAT. This, however, does not exempt an applicant from the other admission requirements of a law school if one has been imposed.

Thus, the scheme under LEBMO No. 7 can be summarized as follows:

1. Objective: to measure the academic potential of an applicant to a law school to pursue a law degree in terms of baseline competencies in communications or language proficiency, critical thinking skills, and verbal and quantitative reasoning.

2. Means: (a) writing the one-day aptitude test on communications or language proficiency, critical thinking skills, and verbal and quantitative reasoning, and passing this test with a score of 55% of correct answers; (b) non-admission of applicants who score less than 55% in PhiLSAT and imposition of administrative fine against law schools admitting law students who did not write or pass PhiLSAT; and (c) law school admission requirements in addition to writing and passing PhiLSAT, if any.

3. Exemption: as stated in No. 10 of LEBMO No. 7.

PhiLSAT as an admission requirement is reasonable because it is minimally impairing of academic freedom.

The scope of the area measured by PhiLSAT is limited to academic potential - communications or language proficiency, critical thinking skills, and verbal and quantitative reasoning - and does not extend to an applicant's personality or emotional quotient.

PhiLSAT competencies are the most basic of skills needed to survive as and gain something from being, a law student. There is nothing fancy, whimsical or arbitrary about these competencies. PhiLSAT does not intrude into a law school's decision to prescribe other admission requirements covering other sets of skills.

Further, PhiLSAT's passing score is minimal - 55%. If an applicant cannot even obtain a score of at least 55% in this test involving the most basic of skills required in a law school, then the applicant's aptitude must lie somewhere else.

A snapshot or sample of PhiLSAT questions bears this out:

TEST A. COMMUNICATION AND LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY

| Section 1. Identifying Sentence Errors

Directions: Read each sentence carefully but quickly, paying attention to the underlined word or phrase. Each sentence contains either a single error or no error at all. If the sentence contains an error, select the underlined word or phrase that must be changed to make the sentence correct. If the sentence is correct, select option D.

In choosing your answers, follow the requirements of standard written English.

|

| Section 2. Sentence Completion

Directions: Choose the word or phrase that, when inserted in the sentence, best fits the meaning of the sentence as a whole.

|

23 Cecilia's mother _________________ from Switzerland 30 years ago, and she found a haven in the Philippines.

(A) emigrated

(B) immigrated

(C) has emigrated

(D) has immigrated

24 After seeing the movie, Andrea took her eyeglasses off and put them _________________ her lap.

(A) to

(B) on

(C) in

(D) at

25 Contemporary Manila, with its images of urbanization and poverty, is _________________ from Old Manila, once romantically described as the Queen City of the Pacific.

(A) a far cry

(B) a grain of salt

(C) the last straw

(D) the wrong tree

26 _________________ the presenter had rehearsed the, part she thought the most difficult, the pa1ticipants did not appreciate her effort and went home unhappy.

(A) Since

(B) Because

(C) If only

(D) Even though

27 Yosef presented to the team _________________ than what the company purchased three years ago.

(A) a powerfuller device

(B) the powerfuller device

(C) a more powerful device

(D) the more powerful device

28 She was answering her assignment on historical background of a short story _________________ she discovered she was in the wrong page.

(A) after

(B) but

(C) and

(D) when

29 After a tight and exhausting schedule yesterday, Ramon _________________ in bed since early this morning.

(A) lay

(B) lying

(C) has lain

(D) had lied

30 The passengers are informed that they have the next four hours _________________ leisure, and can go wherever they wish.

(A) at

(B) by

(C) on

(D) as

31 Because the problem is rather insoluble, even those who initially wanted to take it up have now dropped it like a _________________.

(A) penny for your thoughts

(B) piece of cake

(C) spilt milk

(D) hot potato

32 We are expected to _________________ our outputs on or before Thursday next week.

(A) turn to

(B) turn off

(C) turn in

(D) turn into

33 She was (the) _________________ among the researchers in this institution, despite her formidable credentials.

(A) humbler

(B) humblest

(C) more humble

(D) most humble

LEBMO No. 7 also respects the academic freedom of law schools to impose additional admission measures as they see fit. It is only this minimal requirement of writing and passing PhiLSAT at the very reasonable score of 55% on multiple choice questions that reflects an applicant's capacity for reading, writing, computing and analyzing individual questions and fact scenarios, which the State demands of every law school to factor in as an admission requirement.

More, a law school may admit as students those who have not written and passed PhiLSAT but have obtained professional civil service eligibility within two years from the date of their graduation in college.

In addition, a law school desirous of proving the propriety of another exemption from taking and passing PhiLSAT can very well petition the Legal Education Board for this purpose.

To repeat, While LEBMO No. 7 impacts on a law school's academic freedom, the impairment is minimal and based on rational considerations.

As regards individual applicants to law school, the demand and effect of PhiLSAT upon them thoughtfully account for their dignity as individuals. This is because PhiLSAT relieves an applicant of the potential pain and agony of unmet expectations and wastage of time, resources and efforts. Unsuccessful PhiLSAT examinees may have their aptitude in something else.

In any event, the scheme under LEBMO No. 7 is also very accommodating of applicants who fail the test. PhiLSAT is now offered twice a year, and an applicant can write it as many times as he or she is willing to take.

To stress anew, PhiLSAT as envisioned in LEBMO No. 7 minimally impairs the limited right of a citizen to select a profession or a course of study and a law school's academic freedom, is consistent with the State's power of reasonable regulation and supervision of all educational institutions, and is therefore reasonable.

I conclude, therefore, that there is proportionality between the overall salutary effects of the objectives of PhiLSAT and the deleterious effect of passing PhiLSAT as an admission requirement.

As in the case for Subsection 7(e), the benefits obtained from achieving the objectives are obvious - no one can argue against students who have been measured to have the necessary skills in communications and language, critical thinking, and verbal and quantitative reasoning. On the other hand, the deleterious effect of the imposition of PhiLSAT to stress anew is speculative. There is in fact no evidence of the evils that could be attributed to this minimal admission requirement. It has not been shown that PhiLSAT questions are arbitrary, the test results are oppressive to the examinees (in fact, as shown above, easily more than half of the applicants have passed the first versions of PhiLSAT), or the scope of PhiLSAT has occupied the entire field of admission standards and has left nothing for law schools to prescribe. These allegations have not been proven to be true.

Existence of Transparency and Intelligibility. PhiLSAT has had a long history of validation and re-validation that both the Decision and the Memorandum of the Office of the Solicitor General have been able to recount succinctly. The bases for which PhiLSAT was conceived and required for applicants to law school have thus been made transparent and intelligible. One can therefore concede that PhiLSAT was not the result of an arbitrary and capricious exercise of wisdom by its authors.

Action as being within a range of possible, acceptable and defensible outcomes. It is open to the Legal Education Board to impose PhiLSAT as one of several measures to achieve the constitutional objective of quality education. In fact, a mandatory law school admission test was one of the reform agenda to improve the quality of the instruction given by law schools as recommended by the Court's Special Study group on Bar Examination Reforms, and later, by the Committee on Legal Education and Bar Matters and the Court's Bar Matter No. 1161.

To reiterate, both Subsection 7(e) of RA 7662 and LEBMO Order No. 7 on PhiLSAT are reasonable forms of State regulation and supervision of law schools.

I also reflect on some of the Decision's ratio.

I refer to the presumption that the legislature intended to enact a valid, sensible and just law and one which operates no further than may be necessary to effectuate the specific purpose of the law. In a word, Subsection 7(e) and LEBMO No. 7 are presumed to be reasonable.

As reasonableness is a fact-heavy determination, absent evidence of unreasonableness from petitioners, it would be speculative to jump to the conclusion that PhiLSAT is in fact unreasonable. Petitioners need to prove facts to disprove the presumption.36

I agree that the subject of PhiLSAT is to improve the quality of legal education, which falls squarely within the scope of police power.

But I do not agree that PhiLSAT is irrelevant to such purpose and that it is further arbitrary and oppressive. In the first place, I do not share the view that there is an apparent discord between the purpose of improving legal education and prescribing a qualifying and restrictive examination because the design of the PhiLSAT itself appears to be disconnected with the aptitude for law that it seeks to measure. The discussions above should prove that PhiLSAT is not only relevant to the objectives set out by the Constitution and RA 7662 but is also proportionate as a means to these objectives.

Notably, petitioners presented no evidence on these factual issues. Hence, it cannot be said that the ratio in the Decision is based on facts and circumstances. There is not even a discussion in the Decision on the structure and contents of the PhiLSAT tests that have been administered thus far. To be sure, the absence of an evidentiary record makes the Decision's conclusions at best speculative.

An evidentiary record is important because the Decision itself recognizes the presumption that the legislature intended to enact a valid, sensible and just law and one which operates no further than may be necessary to effectuate the specific purpose of the law. Yet, although petitioners adduced no contrary evidence, the Decision goes on to conclude that the presumption of validity has been rebutted.

If there is any evidence on record here, it is to the effect that LEBMO No. 7's PhiLSAT actually measures a potential law student's aptitude for law. As the Decision itself acknowledges, the PhiLSAT is essentially an aptitude test measuring the examinee's communications and language proficiency, critical thinking, verbal and quantitative reasoning, and that i was designed to measure the academic potential of the examinee to pursue the study of law.

There is no denying that the ability to read a large volume of material in English and write, think and argue in English are important indicators of one's ability to complete a law degree. While PhiLSAT is not an exact predictor of success in law school, it is its undeniable role in measuring a student's strong potentials for success that must be taken into account.

Further, as the Decision itself notes, the Court, through Resolution dated September 4, 2001, approved the recommendations of our own Committee on Legal Education and Bar Matters, including "d) to prescribe minimum standards for admission to law schools including a system of law aptitude examination[.]" The Court could not have recommended a measure that would have been an unreasonable imposition on potential students of law or on academic freedom.

Some law schools are already imposing strict admission standards. That is true. But this fact does not automatically render PhiLSAT irrelevant or unreasonable.

PhiLSAT would not have come into being had there been no legitimate concerns about improving the state of our legal education. The top law schools are precisely top law schools because of strict admission standards they have in place.

These law schools, however, are not the only law schools in the Philippines. They do not have the monopoly of law students in the country. In fact, they are only a minority. There are so many more law schools and law students out there, whose state of competencies LEBMO No. 7 seeks to capture.

It is also a contradiction in terms that we land the best admission standards and practices of some law schools, yet reject the passing of PhiLSAT as a requirement for law school admission. Their standards and practices indubitably prove a reasonable connection between the regulation of admissions to legal education and in ensuring that those allowed to study law and eventually allowed to practice law are competent, knowledgeable or morally upright.

But these law schools are not the reason why we are debating about how to improve legal education standards. If every law school has exercised responsibly their role in ensuring that admission standards and practices are up to par with quality legal education, we would not be talking about requiring PhiLSAT anymore.

The indubitable social and legislative facts prove that . a screening mechanism like PhiLSAT is necessary. If we are again going; the way of making such screening mechanism an optional device for law school admission, as the Decision does, then the Court is not just overhauling the undeniable social and legislative facts upon which Subsection 7(e) of RA 7662 was based, the Decision is also turning its back to the problems that have long beset our legal education.

Common sense dictates that the absence of filters would clog sooner than later the pipeline of knowledge. PhiLSAT acts as that filter which removes students whose capacity, values, forbearance and aptitude may not be for the study of law. This is true for aspiring law students (there must be a State-imposed method to determine an entry level student's aptitude, capacity, forbearance and values for law study) as it is true for those who want to be appointed to the Bench (where the battery of tests administered by the JBC presumably makes not only for a fair selection process but also for a pool of competent aspirants).

I do not agree that the imposition of the PhiLSAT cut off score was made without the benefit of a prior scientific study, thereby making it arbitrary. To my mind, this is a reversal of the onus of who proves what. Since the Decision admits the existence of the presumption that the legislature intended to enact a valid, sensible and just law and one which operates no further than may be necessary to effectuate the specific purpose of the law, it is up to the petitioners to establish that Congress - both the House and the Senate - and the Legal Education Board acted arbitrarily. Petitioners did not adduce evidence to this effect.

On the contrary, the other Branches of Government have tests validating PhiLSAT. It is not for these Branches of Government to explain the relevance and validity of these studies if, on their face, these studies appear to be relevant. The actions of these Branches of Government are entitled to deference not only because of the presumption above-mentioned but also due to their status as agents of sovereignty. Again, the burden is on petitioners to prove by evidence their claim that PhiLSAT is arbitrary for having been imposed without prior scientific study, or that petitioners' own studies disprove the presumption.

I also do not think that it is arbitrary and harsh to impose penalties upon law schools that do not make PhiLSAT a requirement for law school admission.

Again, petitioners have not adduced evidence that unduly oppressiveness will be the case. In any event, there is nothing oppressive about penalizing an entity that does not comply with regulations. This setup of regulatory and even criminal penalties has been done so often to deter violations and enforce obedience. This is especially true where the regulation involved is intended towards a socially positive and uplifting goal, but compliance is not assured.

In addition, whether to attach a penalty to a measure is a policy and not a legal decision. The decision to impose a penalty speaks to the utility and wisdom or desirability of the manner by which breach of the regulation is deterred, and compliance, maximized.

There is, too, further nothing abusive about the scoring methodology in LEBMO No. 7. It is common among law schools that examinations are graded based on a minimum percentage of correct answers and not on a percentile score. The Supreme Court's Bar examinations are scored on the basis of correct and wrong answers, and passers are those who reach the minimum required scores.

The ruling in Tablarin37 is relevant. This case law focused on the validity of the National Medical Admissions Test (NMAT) as a valid and reasonable police power measure as an admission standard into medical schools. Tablarin held that NMAT is an educational regulatory tool related to one of the legitimate objectives of police power - public order, specifically, securing of the health and physical safety and wellbeing of the population. Tablarin also recognized that though NMAT is at the most initial and lowest rung of the requisites to attain this police power objective, NMAT is nonetheless an essential part of the police power objective. Tablarin confirmed that NMAT serves as a gate-keeping measure to weed out misfits in the sense of those whose aptitude and inclinations are not for the field of medicine. The fact that NMAT was described by the Court as a factor in becoming better doctors (or medical practitioners) does not detract from the ruling in Tablarin that NMAT is first and foremost a legitimate screening device for those wishing to be admitted to medical schools.

Hence, NMAT serves the same function as that of PhiLSAT. Because PhiLSAT is the NMAT equivalent in essential respects, the ruling in Tablarin justifying NMAT as a legitimate police power exercise should also apply to the cases-at-bar about PhiLSAT.

PhiLSAT serves an equivalent function as the LSAT. LSAT is a standardised test designed to identify individuals who are likely to succeed in first year law school. Unlike in PhiLSAT which is a State-sponsored measure, all law schools in North America require applicants to take LSAT. LSAT is administered by a non-profit corporation located in the United States.

LSAT, like PhiLSAT, is a screening device for entry into the great learning of the law. The theory behind both LSAT and PhiLSAT is that law schools seek students who have substantial promise for success in law school, and as a result, a strong likelihood of succeeding in the practice of law as shown by their preliminary aptitude for law.

To be sure, we cannot distance or segregate law school experience from the practice of law because the former should ideally segue to the latter. Law schools do not exist exclusively just to teach law students; law schools are also there to transform their students into lawyers. It is unrealistic to say otherwise.

If law schools were to simply exist to teach without regard to whether their students become lawyers, law school education would lose both its clientele and its relevance in the real world - this is the common sensical and obvious context of the educative process. Despite the division of authority as between legal education and practice of law and the obvious difference between them, in reality, one bridges to the other as one cannot be dissociated from the other.

The difference between LSAT and PhiLSAT is not conceptual but operational - that is, how much weight is to be given by institutions of higher learning - the law schools - to the scores obtained by an examinee. They also differ in the scoring system - LSAT is percentile-based while PhiLSAT as now envisioned is raw score-based.

Most law schools in common law countries have several streams about how an applicant is to be admitted as a law student. The most common if not the only stream is through high LSAT scores and grade point averages. So it is a common goal for those asp1nng to enter law schools in those countries to take LSAT and aim for high LSAT percentiles and GPAs.

Among these law schools, there may be other streams of admission those who have achieved extensive relevant experiences abroad or in-country and those who would bring interesting diversity to the law school student population. But the number of these students vis-a-vis the entire population of law students in a law school is miniscule. The students admitted through these other streams constitute a very small minority of the entire population of law students.

The majority are still required to show competence through LSAT scores. The lower scores an applicant has, the lower the chance the applicant can get to enroll in a law school - IF THEY HAVE ANY CHANCE AT ALL.

In any event, LSAT is not anchored on a State sponsored measure. Why the countries under LSAT regimes do not require State supervision and regulation could be attributed to their perception that their law societies (the equivalent of our Integrated Bar) and law schools are mature enough to self regulate.

If we had no concerns about law schools which have no proportionate standards to the nobility of legal education, then perhaps we can adopt as liberal a policy as the countries utilizing LSAT and having different admission streams. But obviously, our experiences are not the same as their experiences; our situation is not similar to their situations.

In any case, PhiLSAT tries to mirror the admission practices where LSAT is the screening device. If LSAT can be waived in exceptional circumstances, this exceptional stream where LSAT is waived is akin, in the case of PhiLSAT, to recall from above, to the exemption under No. 10 of LEBMO No. 7 for honor graduates.

PhiLSAT as embodied in LEBMO No. 7 is not objectionable for being unreasonable. Having been imposed by a law that carries the presumption of validity and reasonableness that has not been disproven by contrary evidence from petitioners' end, PhiLSAT cannot be ignored or set aside as this has been imposed by the State through an administrative regulation-LEBMO No. 7 - which finds its basis in RA 7662.

I agree with the Decision that the reasonable supervision and regulation clause is not a stand-alone provision but must be read in conjunction with the other constitutional provisions which include, in particular, the clause on academic freedom. I agree as well that institutions of higher learning has a wide sphere of autonomy certainly extending to the choice of students.

Yet, this sphere of autonomy is not absolute or limitless. Autonomy cannot result in arbitrary or discriminatory admission policies. If autonomy were to have such a result, restrictive police power can curb such actuality or tendency. Autonomy too cannot disregard the constitutional power of the State to exercise reasonable regulation and supervision of all educational institutions. Thus, I agree with the Decision that affirmative police power can be legitimately exercised in the regulation and supervision of institutions of higher learning. The Decision aptly ruled that institutions of higher learning enjoy ample discretion to decide for itself who to admit, being part of their academic freedom, but the State, in the exercise of its reasonable supervision and regulation over education, can impose minimum regulations. This is what RA 7662 and LEBMO No. 7 have done.

The issue is not whether the State can intervene in the admission requirements of law schools or any other institution of higher learning - the rule of law has already said the State can. The issue is whether the degree and breadth of the intervention that the State can legally do is reasonable supervision and regulation.