Manila

THIRD DIVISION

[ G.R. No. 259815 (Formerly UDK 17421), August 05, 2024 ]

MAZY'S CAPITAL, INC., PETITIONER, VS. REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES, REPRESENTED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF NATIONAL DEFENSE, RESPONDENT.

D E C I S I O N

CAGUIOA, J.:

Before the Court is a Petition for Review on Certiorari under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court1 (Petition) filed by petitioner Mazy's Capital, Inc. (Mazy's) against respondent Republic of the Philippines (Republic), represented by the Department of National Defense (DND), assailing the Decision2 dated March 20, 2020 and Resolution3 dated September 30, 2021 issued by the Court of Appeals (CA), Cebu City in CA-G.R. CV No. 05860.4 The CA reversed the dismissal of the Republic's Complaint for cancellation of reconstituted title and remanded the case to Branch 12, Regional Trial Court (RTC), Cebu City (RTC-Br. 12) for further proceedings.

The Facts and Antecedent Proceedings

The controversy involves a 46,143-square meter property known as Lot No. 937 (Lot 937 or subject property) located in Cebu City. Lot 937 was part of the Banilad Friar Lands Estate (Friar Lands) which has been the subject of several disputes that have reached the Court through the years.5 Much like the other Friar Lands cases, the Court is again faced with the issue of who between two contending parties is the rightful owner of the disputed property, the determination of which is best resolved after the Court first exhaustively examines the history of the present case.

Civil Case No. 781:

1938 Expropriation Proceedings

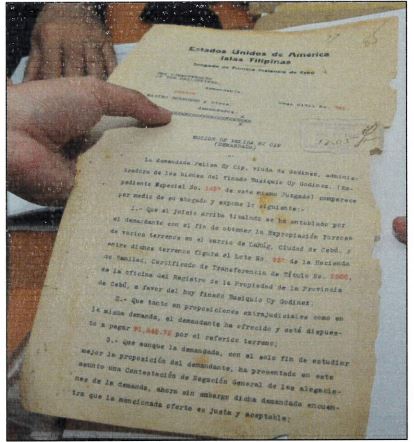

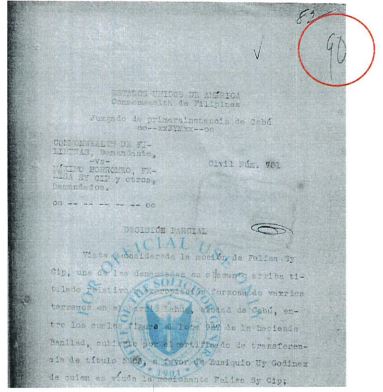

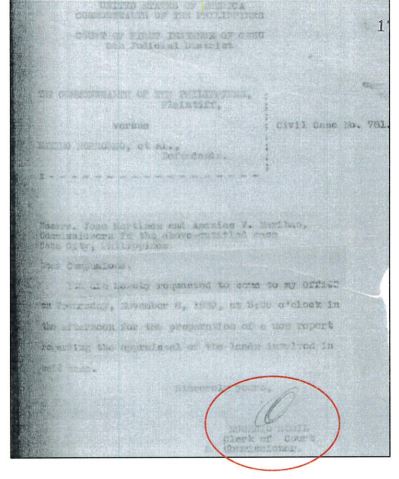

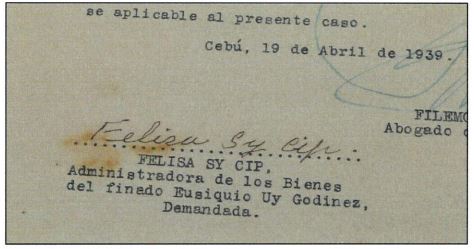

On September 5, 1938, or 86 years ago, the Commonwealth of the Philippines (Commonwealth) filed before the Court of First Instance of Cebu (CFI), an expropriation complaint6 against various landowners of the Friar Lands, which was docketed as Civil Case No. 781 (Expropriation Case). The purpose of the expropriation was to carry out the development program of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) under the National Defense Act.7 Among the parcels of land included in the Expropriation Case was Lot 937 which was registered under Transfer Certificate of Transfer (TCT) No. 53068 in the name of Eutiquio Uy Godinez9 (Eutiquio), married to Felisa Sy Cip10 (Felisa). Lot 937 was provisionally valued at PHP 1,845.72 in the Commonwealth's complaint.11 As administratrix of Eutiquio's estate, Felisa filed her Answer.12 In due course, the Commonwealth deposited the amount of PHP 9,500.00 with the Provincial Treasurer of Cebu as provisional value of all the lots to be expropriated.13 Thereafter, the Commonwealth supposedly took possession of Lot 937.14

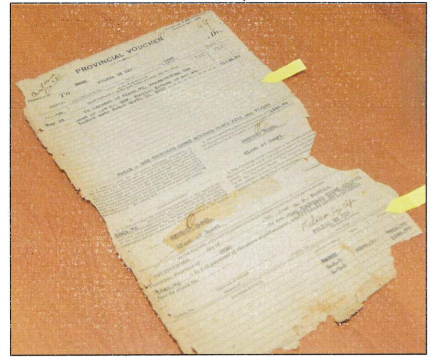

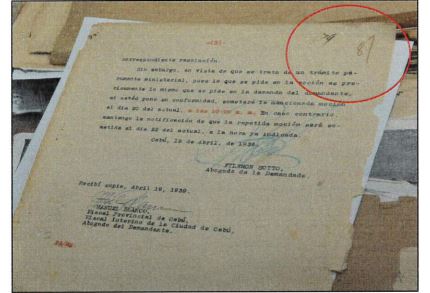

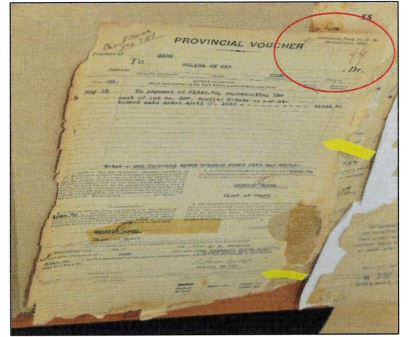

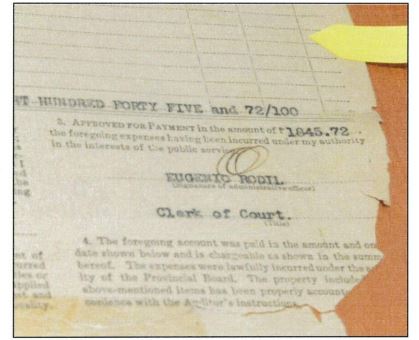

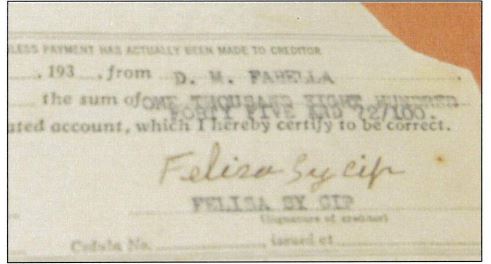

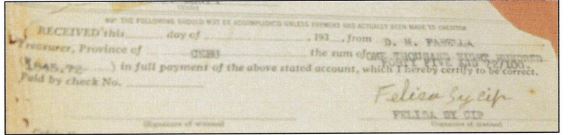

During the pendency of the proceedings, Felisa filed a motion15 stating that she found the value of PHP 1,845.72 acceptable as just compensation for Lot 937 and prayed that the Commonwealth, which was already in possession of Lot 937, be ordered to pay her the said amount.16 The CFI granted Felisa's motion in a Decision Parcial17 dated April 22, 1939 (1939 Partial Decision). Pursuant thereto, the Commonwealth supposedly paid Felisa the amount of PHP 1,845.72, as evidenced by a Provincial Voucher18 dated May 25, 1939.

Eventually, the CFI rendered a Decision19 dated May 14, 1940 (1940 Decision), which set the amount of just compensation for each of the expropriated lots and ordered the government to pay the same. As regards Lot 937, the CFI deemed the same as already resolved based on the 1939 Partial Decision.20

World War II broke out in the Philippines in 1941 which ended only in 1945 after the Battle of Manila when the Philippines was liberated from Japanese occupation.ℒαwρhi৷ The disruption by the war caused several controversies over the legal ownership and possession of the Friar Lands between the Philippine Army and the landowners and possessors thereof. Based on Federated Realty Corporation v. CA,21 all 18 lots subject of the Expropriation Case were later converted into a national airport in 1947 by virtue of a Presidential Proclamation.22

G.L.R.O. Record No. 5988:

1954 Reconstitution of Title Case

On March 12, 1954, a Petition for Judicial Reconstitution of Title23 was filed with the CFI. The petition was filed by Ramona U. Agustines, a supposed attorney-in-fact of Mariano Godinez (Mariano), Eutiquio's son, and alleged that Mariano inherited the property from Eutiquio and was the registered owner of Lot 937 which was covered by a title before the war; and that due to loss of records, the title number could no longer be determined. The petition claimed that Mariano was in possession of the property and that it was not encumbered, pledged, or sold. The case was docketed as G.L.R.O. Record No.(awÞhi( 5988 (Reconstitution Case).

In an Order24 dated March 1, 1956, the CFI granted the petition after finding that: (1) Mariano was the registered owner of the lot; and (2) both the owner's duplicate and the original copy of a certificate of title covering Lot 937 kept in the office of the Register of Deeds of Cebu had been lost or destroyed during the war. The CFI thus directed the Registry of Deeds of Cebu to issue a reconstituted title in the name of Mariano. Accordingly, Mariano was issued TCT No. RT-6757.

Civil Case No. CEB-19845:

1997 Reivindicatoria Action

On January 27, 1997, Eugenio Amores and Domingo Antigua, supposed attorneys-in-fact of Mariano, filed with Branch 9, RTC, Cebu City, (RTC-Br. 9) a reivindicatoria complaint25 against the Republic, alleging that Mariano is the absolute and exclusive owner of Lot 937.26 The case was docketed as Civil Case No. CEB-19845 (Reivindicatoria Case). In the complaint, it is alleged that Mariano was always in possession of the property through his overseer until the early 1990s when the Republic, through the Philippine National Police (PNP), took possession of the same based on the expropriation case notwithstanding the non-payment of just compensation. The PNP allegedly entered the property and constructed buildings and other structures on the property.27

In a Decision28 dated April 18, 2002, the RTC-Br. 9 ruled that Mariano was the absolute and exclusive owner of Lot 937,29 as evidenced by TCT No. RT-6757,30 and that he remained as such since the Expropriation Case was never consummated because the Republic failed to prove the payment of just compensation. The fact of non-payment was based on the following findings: (1) the Republic did not present any deed of sale; (2) the Republic has not transferred the title of Lot 937 to its name, even though the Expropriation Case was decided as early as 1940; (3) no annotation of the judgment of expropriation on the title of the property was made; (4) no motion for execution or motion for issuance of writ of possession had been filed by the Republic in the Expropriation Case; (5) the testimony of Mariano's attorneys-in-fact that there was no payment; (6) the provisional deposit presented by the Republic during the proceedings was insufficient to prove payment of just compensation since there is no indication that the amount was disbursed or that it was received by the concerned parties; and (7) the Province of Cebu donated 47 lots with an area of 81 hectares to the Republic which the RTC-Br. 9 considered as one of the reasons why the Republic did not bother to pay the just compensation, to have the judgment in the expropriation proceedings annotated, or to cause the title of Lot 937 to be transferred to its name.31 Likewise, the RTC-Br. 9 determined that the Republic could no longer seek the enforcement of the 1940 Decision in the expropriation case which has become stale for failure of the Republic to seek its enforcement under Rule 39, Section 6,32 of the 1997 Rules of Court.33

Upon appeal by the Republic, the CA affirmed the trial court's decision. The CA agreed with the RTC's finding that the Republic failed to prove its payment of just compensation. The CA noted that the 1940 Decision did not order the expropriation of Lot 937 but only mentioned the property in reference to the earlier issued 1939 Partial Decision of Judge Benito Natividad. However, while the Republic submitted a copy of the 1939 Partial Decision as part of its evidence, the copy provided was in Spanish and no official translation was provided. Thus, the CA did not give any evidentiary weight and credence thereto.34

This CA decision became final and executory when no appeal was filed by the Republic.35 Thereafter, the RTC-Br. 9, upon Mariano's motion, issued writs of execution and demolition in 2010.36

In the meantime, Archangels Residents Mergence Inc. (ARMI), which claimed to represent the residents of Lot 937, filed a motion to quash the writs before the RTC-Br. 9. Upon denial of the motion, ARMI filed a Rule 65 petition with prayer for a writ of preliminary injunction before the CA, docketed as CA-G.R. SP No. 05751. The CA issued a writ of preliminary injunction on July 21, 2011. On February 1, 2012, the CA dismissed ARMI's petition since it was filed out of time.37 The CA also ruled that ARMI merely occupied Lot 937 by authority of the AFP. Thus, the CA ruled that ARMI was merely an agent of the Republic which did not have a separate and independent right over the lot. ARMI elevated the matter before the Court, docketed as G.R. No. 201766, to challenge the CA decision. However, the Court dismissed the petition since the verification was defective and ARMI failed to prove that the CA committed any reversible error. This became final and executory on January 15, 2013.38

In 2018, the RTC-Br. 9, upon Mariano's motion, issued another set of writs of execution and demolition. This was questioned by the Republic via a Rule 65 petition before the CA in CA-G.R. SP No. 13238, arguing that the RTC's decision could no longer be enforced by mere motion as more than five years had lapsed from the entry of judgment. In a Decision39 dated February 11, 2022, the CA dismissed the Republic's petition. According to the CA, the delay in execution could not be attributed to Mariano since it was caused by ARMI's filing of CA-G.R. No. SP No. 05751 before the CA. Thus, the CA found that the RTC-Br. 9 acted within its jurisdiction in granting the motion and issuance of the writs. The Republic filed a motion for reconsideration which the CA denied on June 23, 2023.40

In the meantime, while the Reivindicatoria Case was the subject of review before the CA, the property was sold by Mariano to Mazy's through a Deed of Absolute Sale41 dated February 15, 2018. Mazy's then caused the cancellation of Mariano's title and TCT No. 107-2018002380 was issued in its name.42

In yet another action to question the writs of execution and demolition issued by the RTC-Br. 9, members of the AFP who reside in Lot 937 filed a petition for annulment of judgment before the CA which was docketed as CA-G.R. SP No. 12553. The AFP members sought the nullification of the RTC Decision dated April 18, 2002 in the Reivindicatoria Case arguing that they should have been impleaded therein as actual occupants and possessors of the property and that Mariano concealed the fact that he was no longer the owner of the property since it had been the subject of an Expropriation Case initiated by the Republic. Mazy's, who had substituted Mariano, filed its Answer praying for the dismissal of the petition on the ground of res judicata. The case was dismissed by the CA on the ground that the AFP members' exclusion from the Reivindicatoria Case did not constitute extrinsic fraud because they were neither indispensable nor necessary parties thereto. As members of the AFP, their possession of the property was merely upon permission of the AFP and, thus, they were bound by the RTC-Br. 9's decision against the Republic.43 The AFP members filed a Motion for Reconsideration which the CA denied on December 13, 2023.44

Despite the numerous cases filed seeking to forestall the implementation of the writs, the demolition of the houses standing on Lot 937 pushed through in September 2022 and was fully implemented by December 14, 2022.45 Thus, the houses and structures purportedly owned by the AFP members and their families were demolished, leaving thereon only a building owned by the AFP Visayas Command.46

The Present Case:

Cancellation of Reconstituted Title

Parallel to the execution proceedings in the Reivindicatoria Case, the Republic, through the DND, filed on May 8, 2013 the present Complaint for cancellation of reconstituted title against Mariano and the Register of Deeds Cebu City.47 The case was docketed as Civil Case No. CEB-3971848 and raffled to Branch 12, RTC, Cebu City (RTC-Br. 12) (Cancellation Case).

As summarized by the CA:

In the Republic's complaint, it prayed for the nullification and cancellation of TCT RT-6757 covering Lot 937 in the name of herein appellee Mariano Godinez (Godinez for brevity) based on the following causes of action: (1) that the Republic is the rightful and lawful owner of a parcel of land known as Lot 937 of the Banilad Estate, originally covered by TCT No. 5306, pursuant to the expropriation complaint filed in 1938 and by virtue of an Order dated October 19, 1938 granting the expropriation case; (2) that the Government's possession and ownership of the subject property had been decided with finality by the Court of First Instance (CFI) of Cebu through a Partial Decision dated April 22, 1939; and (3) that notwithstanding the foregoing, Godinez caused the surreptitious reconstitution of title of the subject property. The Republic maintained that Godinez filed the petition for reconstitution of title over the subject property only on March 12, 1954, or 15 years after the expropriation proceedings in 1938 and payment of just compensation in favor of Godinez's father, Eutiquio Godinez. Said payment was made to the administratrix of his estate, his widow and Godinez'[s] mother, Felisa Sy Cip. The Republic also maintained that the land title of the subject property has not been encumbered, pledged or sold to any person, firm or association [ever since].

Maintaining its objection to the reconstituted TCT in favor of Godinez, the Republic averred that Godinez misrepresented that the subject property was in his possession and that the same has no lien and had not been expropriated by the Republic, thereby deliberately omitting/misrepresenting the fact that the same was previously condemned through . . . expropriation proceedings and was already placed in the possession of the Republic through a writ of possession long issued by the expropriation court in its favor. With the compliance of the Order dated October 19, 1938 by the expropriation court in the said expropriation case, the government is deemed the lawful possessor and owner of the subject property from then on after it had paid the amount of just compensation pursuant to the Partial Decision dated April 22, 1939.

The Republic contended that there was no mention of the Republic's possession of the subject property pursuant to the expropriation proceedings in 1938 in Godinez's petition for reconstitution. Due to such misrepresentation, the Republic, particularly the Department of National Defense (DND), as true and lawful owner and possessor of the subject property, was not notified thereof and accordingly deprived of its right to be heard or even to file an opposition to said petition for reconstitution.49

In support of its assertion that it had already paid the amount of just compensation for Lot 937 during the expropriation proceedings, the Republic attached a Provincial Voucher50 which purportedly shows that Felisa acknowledged having received the amount of PHP 1,845.72 from the Republic in connection with the Expropriation Case.

Invoking the finality of the CA Decision in the Reivindicatoria Case, Mariano filed a Motion to Dismiss on grounds of violation of the rule against forum shopping, res judicata, estoppel, conclusiveness of judgment, lack of jurisdiction or lack of cause of action, prescription, and laches.51

On March 31, 2015, the RTC-Br. 12 granted Mariano's Motion to Dismiss and dismissed the case with prejudice.52 It ruled, among other things, that any affirmative relief that it may grant would affect the validity of the expropriation and the ownership of Lot 937, which issues could no longer be reviewed.53

Aggrieved, the Republic appealed to the CA raising the lone issue of whether the case is barred by res judicata.54

In its appeal,

the Republic asserts that a wrongly reconstituted certificate of title, secured through fraud and misrepresentation in court proceedings cannot be the source of legitimate rights and benefits as [c]ourts cannot, and should not, reconstitute a spurious certificate of title and allow the continuous illegal proliferation and perpetuation thereof.

Pointing out fraud and misrepresentation in the case for reconstitution of title, the Republic harps on the alleged failure of Godinez to mention in his petition how the Republic came into possession of the subject property and the mode by which it was acquired through expropriation proceedings in 1938. Due to Godinez's misrepresentation, the Republic, particularly the Department of National Defense (DND), as true and lawful owner and possessor of the subject property, was not notified of the action taken against it and accordingly deprived of its right to be heard and to file an opposition to said petition for reconstitution.

The Republic prays that the appeal be given due course, and this case be remanded to the RTC for appropriate proceedings.55

It was when the Republic's appeal was pending with the CA that the sale of Lot 937 between Mariano and Mazy's transpired. By virtue thereof, Mazy's was joined in the appeal as a co-defendant-appellee.

On June 10, 2019, the Republic filed an Urgent Omnibus Motion for the Issuance of a Status Quo Ante Order which the CA denied for being moot.56

On March 20, 2020, the CA rendered the assailed Decision, which granted the Republic's appeal and remanded the case to the RTC-Br. 12. The CA held that equity and substantial justice demand that the Republic be given an opportunity to be heard, especially since the issue involves the validity and integrity of a Torrens certificate of title.57 Following Malixi v. Baltazar,58 the CA ruled that the doctrine of finality and immutability of judgments may be relaxed if "its strict application would, in effect, circumvent and undermine the stability of the Torrens System of land registration," as in this case.59

Moreover, according to the CA, Section 11 of Republic Act No. 673260 provides that "[a] reconstituted title obtained by means of fraud, deceit or other machination is void ab initio as against the party obtaining the same and all persons having knowledge thereof."61 Here, the Republic alleges that when the Petition for Reconstitution was filed, there was already an existing Decision dated November 18, 1938 expropriating the subject property together with other lots which were all inside the boundaries of Camp Lahug (now Camp Lapu-Lapu).62 These properties were expropriated by the AFP "to carry out the development program of the Philippine Army as provided in the National Defense Act."63 The subject property is supposedly contiguous to other properties where military facilities, structures, and installations reserved for military use can be found.64 The Republic also asserts that in 1939, it complied with the court's order directing it to pay Mariano's predecessor-in-interest just compensation for the subject property,65 as evidenced by a Provincial Voucher.66 Further, Felisa's motion for payment and the court's order granting it explicitly state that the subject property "is now in [the] possession of plaintiff, Philippine Commonwealth," thereby belying Mariano's claim that he was in possession of the property.67 The CA ruled that these allegations deserve further examination in a full-blown trial on the merits.68

Further, the CA ruled that Republic Act No. 2669 (or the Reconstitution Law) impliedly allows the non-application of res judicata in reconstitution cases. Section 19 of Republic Act No. 26 allows the cancellation of a reconstituted title notwithstanding the rule on res judicata.70 The CA also found that there is no identity in the causes of action between the Reivindicatoria Case and the present Cancellation Case.71 The main issue in the present Cancellation Case is the validity of the reconstituted title, which was not an issue in the Reivindicatoria Case which dealt with the question of ownership.72 Moreover, according to the CA, it appears that the trial court in the Reconstitution Case apparently did not really scrutinize whether the documents presented by Mariano were competent sources of reconstitution under Section 2(f) of Republic Act No. 26.73 A trial on the merits will allow the Republic and Mariano ample opportunity to present evidence in support of the nullity or validity of the reconstituted title.74

Finally, the CA ruled that Mariano's invocation of estoppel and prescription against the Republic has no merit.75 The State cannot be bound by the negligence of its agents.76 The Republic's action has not prescribed pursuant to Article 1410 of the Civil Code which provides that an "action or defense for the declaration of the inexistence of a contract does not prescribe".77

Mazy's filed a motion for reconsideration which the CA denied in its Resolution78 dated September 30, 2021.

Hence, the present Petition.

Mazy's argues that the Cancellation Case is merely a re-litigation of issues already settled in the Reivindicatoria Case where Mariano was adjudged with finality to be the absolute owner of Lot 937. Thus, the present case is barred by res judicata. The Republic was also given a full opportunity to present evidence during the Reivindicatoria Case but failed to do so. Mazy's insists that the CA erroneously applied Section 19 of Republic Act No. 26 which provides that if the lost or destroyed title is subsequently found or recovered and the same is not in the name of the same person in whose favor the reconstituted title has been issued, the register of deeds should bring the matter to the court which shall order the cancellation of the reconstituted title. Considering that the reconstituted title was not issued in the name of another person, but remained in the name of the person who lost the title (i.e., the family of Mariano), Section 19 cannot be applied to the present case. Mazy's also raises that the Republic willfully submitted a false certificate of non-forum shopping by erroneously stating therein that the Reivindicatoria Case is an action for recovery of possession despite knowing that the latter pertained to Mariano's recovery of ownership of Lot 937. In addition, Mazy's assails the CA's finding that the Republic's action cannot be barred by prescription and estoppel.

In its Comment,79 the Republic, through the OSG, claims that Mazy's mistakenly believes that it validly purchased Lot 937 from Mariano whose only proof of ownership is an erroneously reconstituted title when in fact the subject property—a military camp outside the commerce of man—belongs to the Republic by virtue of expropriation proceedings conducted in 1938. Countering the arguments of Mazy's, the Republic raises that the 1939 Partial Decision in the Expropriation Case takes precedence and should prevail over the Decision dated April 18, 2002 in the Reivindicatoria Case, which is a void judgment. The Republic likewise insists that it is not seeking to recover ownership or possession of Lot 937 because it is already the true and lawful owner and possessor thereof since 1939. The Republic is merely seeking the nullification of the reconstitution proceedings and the issuance of TCT No. RT-6757 to Mariano considering that he fraudulently secured the title to the subject property despite the expropriation thereof and payment of just compensation to his mother Felisa. Contrary to the assertion of Mazy's, the Republic never wavered in objecting to Mariano's reconstituted title. The Republic, through the DND, was not notified of the reconstitution proceedings and was not a party to the case. Moreover, proof of payment of just compensation for Lot 937 has been found and is a supervening event which renders the supposed finality of the Reivindicatoria Case inequitable. Thus, res judicata cannot be applied to the present case and even if it does, the rule allows for certain exceptions. The CA also correctly applied Section 19 of Republic Act No. 26 because TCT No. 5306 was registered in the name of Eutiquio Godinez and not the "family of Mariano Godinez" as Mazy's asserts. Thus, the issuance of a reconstituted title which is attended by fraud is void ab initio and may be attacked at any time considering that it is not barred by the statute of limitations.

Given the complexity of the facts and issues presented and the intertwining of different cases involving the subject property, the Court found it proper to call the case for Oral Arguments. A Preliminary Conference was held on January 25, 2023 where the counsels for the parties were directed to coordinate with each other and submit to the Court a Stipulation of Facts, their respective Position Papers, and a map depicting Lot 937 and detailing, as of the filing of the Petition: (a) the lot area; (b) the portions occupied; (c) the identity of the occupants thereof; (d) the right by which they occupy the portions of the subject property; and (e) the structures found therein.80

On February 17, 2023, in compliance with the Court's directive, the parties submitted a Joint Stipulation of Facts81 as well as their respective Position Papers.82

The Court held Oral Arguments on February 22, 2023. In the course of the proceedings, the OSG stated that it had located the original Provincial Voucher in the records of the Expropriation Case, which was then inside the archives of the RTC of Cebu City.83 During the hearing, the Court resolved to conduct an ocular inspection of Lot 937 and of the case records of both the Expropriation Case and the Reconstitution Case. Both parties likewise agreed to the conduct of the ocular inspection.

Immediately after the February 22, 2023 Oral Arguments, the Court directed the Executive Judge of the RTC, Cebu City to locate and take custody of the records in both the Expropriation Case and the Reconstitution Case, and to keep the same secure.84 On February 28, 2023, the Executive Judge reported to the Court that he had already taken custody of the said records, as instructed, and has employed all security measures necessary to preserve their integrity and completeness, especially the Provincial Voucher.85

On March 16, 2023, Mazy's filed a Manifestation and Motion86 objecting to the conduct of the ocular inspection and insisting that the present petition be resolved on the basis of the legal issues raised since factual issues are not the proper subject of a Rule 45 petition. In the alternative, Mazy's prayed that the present petition be dismissed, and the case be remanded to the RTC for further proceedings. In opposing the conduct of the ocular inspection, Mazy's argued that: (1) the decisions in the Reconstitution and Reivindicatoria Cases were judgments rendered by courts of proper jurisdiction and cannot be invalidated; (2) Mazy's is an innocent purchaser for value and had the right to rely on the clean title of Mariano as well as the final and executory judgment in the Reivindicatoria Case; (3) the genuineness and due execution of the Provincial Voucher cannot be determined by a simple ocular inspection. According to Mazy's, the Provincial Voucher cannot be considered a public document under Section 19, Rule 132 of the Rules of Evidence and has not been authenticated in accordance with Section 20, Rule 19 of the same Rules. It likewise cannot be considered as an ancient document under Section 21, Rule 132 since it was not produced from a custody in which it would naturally be found if genuine. Custody here supposedly pertained to only two proper custodians: (1) the Provincial Treasurer of Cebu; or (2) Felisa or her heirs. Mazy's argued that, in fact, the Office of the Provincial Treasurer issued a Certification87 that the purported Provincial Voucher is not found in its records. Meanwhile, Catalina Sun Diamante, Felisa's granddaughter, executed a Judicial Affidavit88 attesting that the purported signature of Felisa appearing on the Voucher is a forgery as Felisa never signed her name as "Felisa Sy Cip", did not know how to read and write, and only spoke Chinese.

Despite Mazy's protestations, the Court conducted the ocular inspection of Lot 937 and the records of the Expropriation Case and the Reconstitution Case on March 23, 2023 where both parties were present and accounted for. The Court was able to personally examine the records of the Expropriation Case and the Provincial Voucher found therein. Likewise, the Court was able to inspect Lot 937 with the assistance of both parties, observing that the structures previously built thereon have already been demolished except for a building owned by the AFP Visayas Command, a portion of which apparently encroached on Lot 937. After the ocular inspection, the Court reiterated its directive to the parties to submit their Position Paper on Non-Stipulated Facts and their respective Legal Memorandum.

On April 19, 2023, the Office of the Executive Judge transmitted to the Court the entire original records, with certified true copies, of the Expropriation Case and the Reconstitution Case.89 These records were immediately secured by the Court.90

On July 19, 2023, Mazy's filed its Position Paper [Re: Matters Not Stipulated by the Parties]91 and its Memorandum92 dated July 19, 2023. Thereafter, a Supplemental Position Paper93 was filed on September 4, 2023. In fine, Mazy's argues that:

1. The Republic is barred from relitigating the same issues in this case because of the rule on stare decisis. The cases of Valdehueza v. Republic,94 Republic v. Lim,95 Federated Realty Corporation v. CA,96 and San Roque Realty and Development Corporation v. Republic97 have already established the Republic's failure to complete the expropriation of lots in the Banilad Friar Land Estates;98

2. The present case is barred by res judicata and forum shopping;99

3. The Republic is barred by estoppel by laches from pursuing the present case;100

4. Mazy's is an innocent purchaser for value;101

5. The present petition must be resolved purely on legal grounds. The Court is not a trier of facts;102 and

6. The Court cannot consider the Provincial Voucher as evidence.103 It is not newly discovered evidence.104 It was not formally offered in evidence.105 It is a private document that should have been authenticated in accordance with the Rules on Evidence.106

Thus, Mazy's prays: (1) that the Petition be resolved on the basis of the legal issues raised in the pleadings; (2) that judgment be rendered reversing and setting aside the CA's Decision dated March 20, 2020 and Resolution dated September 30, 2021 and that the RTC-Br. 12's Order dated March 31, 2015 be reinstated.107

Meanwhile, the OSG filed its Position Paper (On Non-Stipulated Facts)108 and its Legal Memorandum109 dated July 20, 2023. It also filed a Supplemental Stipulation of Facts110 on September 22, 2023. In summary, the OSG raised the following arguments:

1. The Court should settle all issues involving Lot 937;111

2. The Provincial Voucher is authentic;112

3. Lot 937 is a property of public dominion which is outside the commerce of man;113

4. The Reconstitution and Reivindicatoria Cases were filed by persons with no authority from Mariano;114

5. The reconstitution decision is void for lack of jurisdiction, in view of non-compliance with the requirements of Republic Act No. 26.115 Further, the reconstitution petition did not allege and prove the fact of loss of the title sought to be reconstituted;116

6. The Reivindicatoria Case is void. The Expropriation Case takes precedence over the Reivindicatoria and Reconstitution Cases.117 After the payment of just compensation, ownership of Lot 937 transferred to the Republic. Mariano and Mazy's cannot have a title greater than Eutiquio;118

7. Mazy's is not an innocent purchaser for value.119 The innocent purchaser for value defense cannot be invoked when lands of the public domain are involved since they are inalienable and outside the commerce of man.120 Estoppel does not operate against the State.121 The national security and defense of the State outweigh the alleged rights of Mazy's.122

The OSG ultimately prays that the Court deny Mazy's Petition, declare as void the Reconstitution and Reivindicatoria Cases, cancel TCT No. 107-2018002380 issued in the name of Mazy's, invalidate the sale of Lot 937 to Mazy's, and declare the Republic as the absolute owner of Lot 937.123

Issue

At first glance, it would appear that the main issue to be resolved in this case is merely whether the Reconstitution Case should be nullified for noncompliance with Republic Act No. 26.

However, it must be remembered that a court's jurisdiction over the issues of a case, or its power to determine matters disputed by the parties, is generally determined by the allegations in the parties' pleadings and submissions.124 In this case, a close reading of the parties' submissions reveals that the controversy ultimately stems from the primordial issue of whether the Republic had paid the amount of just compensation in the Expropriation Case. On the one hand, the Republic's present Complaint essentially alleges that it made such payment, as evidenced by a Provincial Voucher, a copy of which it attached to its Complaint. Mariano's failure to disclose this fact in the Reconstitution Case supposedly amounts to fraud which warrants the nullification of the reconstitution proceedings, Mariano's TCT No. RT-6757, and all its derivative titles, if any.125 On the other hand, Mazy's maintains that no such payment was made and that the Provincial Voucher is spurious. According to Mazy's, the Republic's failure to prove that it paid just compensation has been finally settled in the Reivindicatoria Case and can no longer be relitigated in the present case.

Clearly, therefore, this case centers on resolving the issue of whether the Republic had in fact paid the amount of just compensation for Lot 937. The intricate and complex web of interrelated and interdependent issues that arose from the passage of time and the Reconstitution Case, the Reivindicatoria Case, and the present Cancellation Case, all ultimately find its origin in the Expropriation Case. And, at the heart of the Expropriation Case is the determination of whether or not payment of just compensation had been made. Thus, the Court finds it indispensable to review the disposition of the Expropriation Case, given that its records are in the Court's custody, and determine its impact on the decisions rendered in the Reconstitution Case and the Reivindicatoria Case.

If the Court finds that the Republic had made such payment, then such operated to transfer ownership of Lot 937 to the Republic at that time. If so, then the Court must determine the current rights of both Mazy's and the Republic in view of the supervening events that had transpired since the time of such payment. As to the other issues raised by the parties (e.g., the authenticity and admissibility of the Provincial Voucher, res judicata, the validity of the decisions in the Reconstitution Case and the Reivindicatoria Case, Mazy's status as an innocent purchaser for value)—all these revolve around this central question.

Ruling

I. Preliminary Procedural Matters

Before the Court resolves the central issue pointed out earlier, there are several procedural matters which the Court must wade through.

A. RTC's Jurisdiction

Mazy's questions the RTC-Br. 12's jurisdiction, arguing that the Republic's Complaint is actually an action for annulment of judgment under Rule 47 as it seeks to nullify the judgment or order of the CFI that rendered a decision in the Reividicatoria Case. Mazy's asserts that the RTC-Br. 12 has no jurisdiction as it cannot interfere with, much less annul, the orders or judgments of a co-equal court, owing to the doctrine of judicial stability or non-interference.126

The Court is not convinced and will lay to rest any doubts on the RTCBr. 12's jurisdiction in this case.

It is basic that jurisdiction over the subject matter of a case is conferred by law and determined by the allegations in the complaint which comprise the ultimate facts constituting the plaintiffs cause of action.127 The nature of an action and which court has jurisdiction over it are determined based on the allegations and relief sought in the complaint.128

In Denila v. Republic,129 the Court clarified that subject matter jurisdiction is only one of the several aspects of a court's jurisdiction. In order to exercise its powers validly and with binding effect, the court must also have jurisdiction over the issues, which the Court explained in this wise:

Jurisdiction is the basic foundation of judicial proceedings. It is simply defined as the power and authority — conferred by the Constitution or statute — of a court to hear and decide a case. Without jurisdiction, a judgment rendered by a court is null and void and may be attacked anytime. Indeed, a void judgment is no judgment at all — it can neither be the source of any right nor the creator of any obligation; all acts performed pursuant to it and all claims emanating from it have no legal effect.

In adjudication, the concept of jurisdiction has several aspects, namely: (a) jurisdiction over the subject matter; (b) jurisdiction over the parties; (c) jurisdiction over the issues of the case; and (d) in cases involving property, jurisdiction over the res or the thing which is the subject of the litigation. Additionally, a court must also acquire jurisdiction over the remedy in order for it to exercise its powers validly and with binding effect.

... Third, jurisdiction over the issues pertains to a tribunal's power and authority to decide over matters which are either disputed by the parties or simply under consideration. This aspect of jurisdiction is closely tied to jurisdiction over the remedy and over the subject matter which, in turn, is generally determined in the allegations of the initiatory pleading (complaint or petition) and not the result of proof. However, unlike jurisdiction over the subject-matter, jurisdiction over the issues may be conferred by either express or implied consent of the parties.130 (Emphasis in the original; citations omitted)

From Mazy's arguments, it appears that it is questioning the RTC-Br. 12's exercise of jurisdiction over both the subject matter and the issues raised in this case.

At the time of the filing of the complaint, Batas Pambansa Blg. 129,131 as amended, granted the RTC with exclusive original jurisdiction—

"(1) In all civil actions in which the subject of the litigation is incapable of pecuniary estimation;

"(2) In all civil actions which involve the title to, or possession of, real property, or any interest therein, where the assessed value of the property involved exceeds [PHP 300,000.00 or for civil actions in Metro Manila, where such value exceeds [PHP 400,000.00 except actions for forcible entry into and unlawful detainer of lands or buildings, original jurisdiction over which is conferred upon the Metropolitan Trial Courts, Municipal Trial Courts, and Municipal Circuit Trial Courts[.]132 (Emphasis supplied)

Before examining the Republic's Complaint, the Court first lays down the applicable legal principles.

In First Sarmiento Property Holdings, Inc. v. Philippine Bank of Communications,133 the Court en banc ruled that the nature of an action is determined by the principal relief sought in the complaint. The Court distinguished the "nature of the principal action or remedy" from its consequences. Thus, an action involving the recovery of a sum of money may not necessarily be capable of pecuniary estimation if it is merely a consequence of a primary relief, such as an action for support or for foreclosure of mortgage, which cannot be estimated in terms of money and are therefore actions that are incapable of pecuniary estimation.134 Moreover, "if the primary cause of action is based on a claim of ownership or a claim of legal right to control, possess, dispose, or enjoy such property, the action is a real action involving title to real property."135

Now looking at the Republic's Complaint, it is evident that the Republic essentially alleges that: (1) it is the "rightful and lawful owner" of Lot 937, having already expropriated the same and paid the corresponding amount of just compensation in 1939; (2) Mariano did not disclose this fact, among other things, to the CFI in the Reconstitution Case; and (3) such failure amounts to fraud which warrants the nullification of Mariano's TCT No. RT-6757, and all its derivative titles, if any.136 Notably, the Republic did not pray that title to the property be reconveyed to it. It simply prayed for a judgment:

1. To declare as null and void and to order the cancellation of TCT No. RT-6757 covering Lot 937 in the name of defendant Mariano Godinez, as well as its derivative titles, if any;

2. To order defendant Mariano Godinez or any person in possession of the owner's copy of said TCT No. RT-6757 to surrender the same to the Registrar of Deeds of Cebu City;

3. For the Register of Deeds of Cebu City to cause the cancellation of TCT No. RT-6757 as well as of all its derivative titles, if there are any; and

4. To order defendant Mariano Godinez to pay the costs of suit as well as all the damages suffered by the plaintiff.

Other reliefs just and equitable under the premises are likewise prayed for.137

Based on the foregoing allegations, the Court is convinced that the Complaint is one that involves title to real property, not one that is incapable of pecuniary estimation. The principal relief sought is the cancellation of Mariano's title and any of its derivative titles on the ground of fraud supposedly perpetrated in the Reconstitution Case. This theory is premised on the Republic's assertion of ownership over Lot 937.

The next question that comes to fore is whether the assessed value of the subject property falls within the RTC's jurisdiction.

The general rule in real actions is that the complaint must allege the property's assessed value to determine which between the RTCs and the firstlevel courts have jurisdiction over the same.138 Strict compliance with this rule, however, may be relaxed if the assessed value of the property, though not alleged in the complaint, can be identified from the documents annexed to the complaint.139

Here, while the assessed value of Lot 937 was not alleged in the Republic's Complaint, the same can be found in the Reivindicatoria Complaint attached as Annex "P" thereof,140 which states that the assessed value of the property is PHP 3,460,730.00.141 This value places the action within the RTC's jurisdiction.

As to Mazy's argument on judicial stability and non-interference, this also has no merit.

A similar issue was raised in the case of Spouses Aboitiz v. Spouses Po,142 which stemmed from a complaint filed with the RTC to recover land and to nullify the corresponding Original Certificate of Title issued pursuant to a final decision of another RTC acting as land registration court. The RTC ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and nullified the title of the defendants. One of the issues raised before the Court was whether the RTC had jurisdiction to nullify the final and executory decision of the land registration court, considering that only the CA has the jurisdiction to annul judgments of the RTCs. The Court ruled that based on the plaintiffs' complaint, their action was not an action to annul the judgment of the land registration court, but one for reconveyance and annulment of title. Therefore, the RTC had jurisdiction over the case. In so ruling, the Court distinguished these three actions, viz.:

The Spouses Aboitiz argue that Branch 55, Regional Trial Court did not have jurisdiction to nullify the final and executory Decision of Branch 28, Regional Trial Court in LRC Case No. N-208. They claim that ... it is the Court of Appeals that has jurisdiction to annul judgments of the Regional Trial Court.

However, the instant action is not for the annulment of judgment of a Regional Trial Court. It is a complaint for reconveyance, cancellation of title, and damages.

A complaint for reconveyance is an action which admits the registration of title of another party but claims that such registration was erroneous or wrongful. It seeks the transfer of the title to the rightful and legal owner, or to the party who has a superior right over it, without prejudice to innocent purchasers in good faith. It seeks the transfer of a title issued in a valid proceeding. The relief prayed for may be granted on the basis of intrinsic fraud—fraud committed on the true owner instead of fraud committed on the procedure amounting to lack of jurisdiction.

An action for annulment of title questions the validity of the title because of lack of due process of law. There is an allegation of nullity in the procedure and thus the invalidity of the title that is issued.

. . . .

While the Court of Appeals has jurisdiction to annul judgments of the Regional Trial Courts, the case at bar is not for the annulment of a judgment of a Regional Trial Court. It is for reconveyance and the annulment of title.

The difference between these two (2) actions was discussed in Toledo v. Court of Appeals:

An action for annulment of judgment is a remedy in equity so exceptional in nature that it may be availed of only when other remedies are wanting, and only if the judgment, final order or final resolution sought to be annulled was rendered by a court lacking jurisdiction or through extrinsic fraud. An action for reconveyance, on the other hand, is a legal and equitable remedy granted to the rightful owner of land which has been wrongfully or erroneously registered in the name of another for the purpose of compelling the latter to transfer or reconvey the land to him. The Court of Appeals has exclusive original jurisdiction over actions for annulment of judgments of Regional Trial Courts whereas actions for reconveyance of real property may be filed before the Regional Trial Courts or the Municipal Trial Courts, depending on the assessed value of the property involved.

....

Petitioners allege that: first, they are the owners of the land by virtue of a sale between their and respondents' predecessors-in-interest; and second, that respondents Ramoses and ARC Marketing illegally dispossessed them by having the same property registered in respondents' names. Thus, far from establishing a case for annulment of judgment, the foregoing allegations clearly show a case for reconveyance.

As stated, a complaint for reconveyance is a remedy where the plaintiff argues for an order for the defendant to transfer its title issued in a proceeding not otherwise invalid. The relief prayed for may be granted on the basis of intrinsic rather than extrinsic fraud; that is, fraud committed on the real owner rather than fraud committed on the procedure amounting to lack of jurisdiction.

An action for annulment of title, on the other hand, questions the validity of the grant of title on grounds which amount to lack of due process of law. The remedy is premised in the nullity of the procedure and thus the invalidity of the title that is issued. Title that is invalidated as a result of a successful action for annulment against the decision of a Regional Trial Court acting as a land registration court may still however be granted on the merits in another proceeding not infected by lack of jurisdiction or extrinsic fraud if its legal basis on the merits is properly alleged and proven.

Considering the Spouses Aboitiz's fraudulent registration without the Spouses Po's knowledge and the latter's assertion of their ownership of the land, their right to recover the property and to cancel the Spouses Aboitiz's title, the action is for reconveyance and annulment of title and not for annulment of judgment.143 (Emphasis supplied; citations omitted)

In Heirs of Procopio Borras v. Heirs of Eustaquio Borras,144 a certain Eustaquio Borras filed a petition for reconstitution of title before the CFI, alleging that the title to a certain lot owned by his grandfather had been lost. The CFI granted the petition. However, it not only reconstituted the lost title, but it also directed that the same be cancelled and a new one be issued in favor of Eustaquio. When Eustaquio's other co-heirs found out what he did, they ultimately filed a petition for annulment of judgment under Rule 47 with the CA to assail the CFI's order. One of the issues that reached the Court was whether an annulment of judgment was the proper remedy of the co-heirs. The Court ruled in the negative, holding that the proper remedy was an action for reconveyance. The Court held that the CFI's order to transfer the title to Eustaquio was rendered in the exercise of its jurisdiction, and any error therein, even if it amounts to grave abuse of discretion, cannot be the subject of a petition under Rule 47. Thus:

Annulment of judgment may either be based on the ground that a judgment is void for want of jurisdiction or that the judgment was obtained by extrinsic fraud. It is a remedy in equity so exceptional in nature that it may be availed of only when other remedies are wanting.

Lack of jurisdiction as a ground for annulment of judgment refers to either lack of jurisdiction over the person of the defending party or over the subject matter of the claim. In a petition for annulment of judgment based on lack of jurisdiction, petitioner must show not merely an abuse of jurisdictional discretion but an absolute lack of jurisdiction. Lack of jurisdiction means absence of or no jurisdiction, that is, the court should not have taken cognizance of the petition because the law does not vest it with jurisdiction over the subject matter. Jurisdiction over the nature of the action or subject matter is conferred by law.

The petitioner cannot rely on jurisdictional defect due to grave abuse of discretion, but on absolute lack of jurisdiction. The concept of lack of jurisdiction as a ground to annul a judgment does not embrace grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction.

In this case, there is no question that the then CFI had jurisdiction over the petition for reconstitution at inception. Petitioners argue that the order of the CFI in cancelling OCT No. [NA] 2097 and directing the issuance of a new TCT in favor of Eustaquio was in excess and was beyond the scope of a reconstitution case. The purpose of a reconstitution action is merely to reproduce a certificate of title, after proper proceedings, in the same form it was when it was lost or destroyed. Hence, in such action, a trial court cannot order the cancellation of the original title nor direct the issuance of a new TCT in favor of another.

. . . .

Clearly, the reconstitution of a certificate of title denotes restoration in the original form and condition of a lost or destroyed instrument attesting the title of a person to a piece of land. The purpose of the reconstitution of title is to have, after observing the procedures prescribed by law, the title reproduced in exactly the same way it has been when the loss or destruction occurred. A reconstitution of title does not pass upon the ownership of land covered by the lost or destroyed title but merely determines whether a reissuance of such title is proper.

Here, while there is no question that the CFI acted in excess of its jurisdiction when it went beyond ordering the reconstitution of OCT No. [NA] 2097 by ordering its cancellation, and directing the issuance of a new TCT in favor of Eustaquio, nevertheless, such order of the CFI was done in the exercise of its jurisdiction and not the lack thereof.

Jurisdiction is not the same as the exercise of jurisdiction. As distinguished from the exercise of jurisdiction, jurisdiction is the authority to decide a cause, and not the decision rendered therein. Where there is jurisdiction over the person and the subject matter, the decision on all other questions arising in the case is but an exercise of the jurisdiction. And the errors which the court may commit in the exercise of jurisdiction are merely errors of judgment which are the proper subject of an appeal.

The lack of jurisdiction envisioned in Rule 47 is the total absence of jurisdiction over the person of a party or over the subject matter. When the court has validly acquired its jurisdiction, annulment through lack of jurisdiction is not available when the court's subsequent grave abuse of discretion operated to oust it of its jurisdiction.

. . . .

The proper recourse for petitioners should have been to file an action for reconveyance. This is a legal and equitable remedy granted to the rightful owner of land which has been wrongfully or erroneously registered in the name of another for the purpose of compelling the latter to transfer or reconvey the land to him. In an action for reconveyance, the decree of registration is respected as incontrovertible. What is sought instead is the transfer of the property, which has been wrongfully or erroneously registered in another person's name, to its rightful and legal owner, or to one with a better right.145 (Citations omitted)

In Estate of Deceased Spouses Jose Francia and Maura Rivera v. Tan,146 the Court affirmed the nullification of a reconstituted title which was ordered by the RTC in an action for quieting of title and reconveyance.

From the foregoing authorities, it is clear that a void reconstituted title issued pursuant to the order of the CFI or RTC may be assailed before another RTC through an action for reconveyance, annulment of title, or quieting of title, and not necessarily through a petition under Rule 47. What is controlling is the nature of the action as determined by the allegations in the complaint.

In this case, the Republic's Complaint prays for the cancellation and nullification of Mariano's reconstituted title based on fraud committed by Mariano during the reconstitution proceedings. It does not seek to nullify the decision in the Reconstitution Case based on lack of jurisdiction or extrinsic fraud. Since the Republic's complaint involves title to real property and is not in the nature of an action for annulment of judgment, the RTC-Br. 12 has jurisdiction over the subject matter of the complaint.

B. Res Judicata

Another threshold question that confronts the Court is whether the Court may resolve the question of whether the Republic had in fact paid the amount of just compensation for Lot 937, in the face of the decision in the Reivindicatoria Case which has already attained finality. Mazy's invokes res judicata, given the finality of the decision in the Reivindicatoria Case, m arguing that this issue can no longer be determined in this case.147

The Court is not persuaded.

Ordinarily, the finality of the decision in the Reivindicatoria Case should already trigger the doctrine of immutability of judgments and the principle of res judicata by prior judgment. In which case, the Republic would be barred from relitigating the question of ownership over Lot 937. More particularly, the Republic would not be allowed to renew its claim of ownership by now presenting the Provincial Voucher as proof of payment of just compensation, especially when it appears that it had a fair opportunity to do so during the trial in the Reivindicatoria Case.

However, the doctrine of immutability of judgments and the principle of res judicata are not absolute. In many cases, the Court has relaxed them to prevent a miscarriage of substantial justice.148 More importantly, it is settled that these principles do not apply in favor of a void judgment.149

The Court expounds.

The doctrine of immutability of judgment means that "a decision that has acquired finality becomes immutable and unalterable, and may no longer be modified in any respect, even if the modification is meant to correct erroneous conclusions of fact and law."150 Thus, said final decision can no longer be attacked or modified, directly or indirectly, even by this Court.151 Nonetheless, the rule is procedural and may be relaxed to serve substantial justice.152 This is because procedural rules were designed to facilitate and promote substantial justice, not frustrate it.153 The Court's ruling in Barnes v. Padilla154 is instructive:

Phrased elsewise, a final and executory judgment can no longer be attacked by any of the parties or be modified, directly or indirectly, even by the highest court of the land.

However, this Court has relaxed this rule in order to serve substantial justice considering (a) matters of life, liberty, honor or property, (b) the existence of special or compelling circumstances, (c) the merits of the case, (d) a cause not entirely attributable to the fault or negligence of the party favored by the suspension of the rules, (e) a lack of any showing that the review sought is merely frivolous and dilatory, and (f) the other party will not be unjustly prejudiced thereby.

Invariably, rules of procedure should be viewed as mere tools designed to facilitate the attainment of justice. Their strict and rigid application, which would result in technicalities that tend to frustrate rather than promote substantial justice, must always be eschewed. Even the Rules of Court reflects this principle. The power to suspend or even disregard rules can be so pervasive and compelling as to alter even that which this Court itself had already declared to be final.

In De Guzman vs. Sandiganbayan, this Court, speaking through the late Justice Ricardo J. Francisco, had occasion to state:

The Rules of Court was conceived and promulgated to set forth guidelines in the dispensation of justice but not to bind and chain the hand that dispenses it, for otherwise, courts will be mere slaves to or robots of technical rules, shorn of judicial discretion. That is precisely why courts in rendering justice have always been, as they ought to be guided by the norm that when on the balance, technicalities take a backseat against substantive rights, and not the other way around. Truly then, technicalities, in the appropriate language of Justice Makalintal, "should give way to the realities of the situation."155 (Emphasis supplied; citations omitted)

On the other hand, the principle of res judicata—which means "a matter adjudged; a thing judicially acted upon or decided; a thing or matter settled by judgment"156—provides that "an existing final judgment or decree rendered on the merits, without fraud or collusion, by a court of competent jurisdiction, upon any matter within its jurisdiction, is conclusive of the rights of the parties or their privies, in all other actions or suits in the same or any other judicial tribunal of concurrent jurisdiction on the points and matters in issue in the first suit."157 Res judicata embraces two concepts: bar by prior judgment and conclusiveness of judgment.158

Res judicata under the first concept or as a bar against the prosecution of a second action exists when there is identity of parties, subject matter, and cause of action in the first and second actions.159 Under the concept of res judicata as "conclusiveness of judgment," when there is identity of parties in the first and second cases, but no identity of causes of action, "the first judgment is conclusive only as to those matters actually and directly controverted and determined and not as to matters merely involved therein.... Stated differently, any right, fact, or matter in issue directly adjudicated or necessarily involved in the determination of an action before a competent court in which judgment is rendered on the merits is conclusively settled by the judgment therein and cannot again be litigated between the parties and their privies whether or not the claim, demand, purpose, or subject matter of the two actions is the same."160

But again, since it is also a procedural rule, res judicata may be relaxed for the broader interests of substantial justice. In Aledro-Ruña v. Lead Export and Agro-Development Corp.161 (Aledro-Ruña), the Court acknowledged that:

The broader interest of justice as well as the circumstances of the case justifies the relaxation of the rule on res judicata. The Court is not precluded from re-examining its own ruling and rectifying errors of judgment if blind and stubborn adherence to res judicata would involve the sacrifice of justice to technicality. This is not the first time that the principle of res judicata has been set aside in favor of substantial justice, which is after all the avowed purpose of all law and jurisprudence. Therefore, petitioner is not barred from filing a subsequent case of similar nature.162 (Emphasis supplied; citation omitted)

Aside from Aledro-Ruña, the Court has previously relaxed the res judicata rule for the sake of substantial justice in other cases: De Leon v. Balinag,163 Heirs of the late Lourdes Dionisio-Galian v. Dionisio,164 and Agrarian Reform Beneficiaries Association (ARBA) v. Fil-Estate Properties, Inc.165

The present case involves a 4.6-hectare parcel of land which is claimed by the Republic by virtue of the expropriation proceedings which had long been concluded. The dispute over Lot 937 has spanned for decades and has resulted in several cases. In the meantime, numerous residents of Lot 937 have been displaced in the execution of the decision in the Reivindicatoria Case. After many years, the document which is part of extant judicial records that would irrefutably prove that the Republic had paid the full amount of just compensation for Lot 937 has surfaced. To be sure, if there was a final and executory finding in the Expropriation Case with respect to full payment of the just compensation for Lot 937 and its receipt by the owner thereof, then such finding would itself constitute res judicata as to the ownership issue in the Reivindicatoria Case and the issue of the capacity of Mariano to institute the Reconstitution Case. Given these special circumstances, the broader interest of substantial justice will be better served with the relaxation of the procedural rules. The truth cannot be suppressed and must prevail, and the Court is duty-bound to put to rest all uncertainty on the ownership of Lot 937. In this light, the Court finds it unnecessary to discuss the other procedural issues of forum shopping and stare decisis raised by Mazy's.

Before proceeding to the next point, the Court notes that the Republic has thus far failed to sufficiently explain why it was not able to present the Provincial Voucher during the proceedings in the Reivindicatoria Case. The Republic explained that it failed to present the Provincial Voucher because of "unavailability of records"166 and because "[it] could not be found."167 According to the Republic, it was only sometime in 2012 that the OSG was informed by the DND that the Provincial Voucher had been found through the efforts of the occupants of Lot 937.168

However, as pointed out by Mazy's,169 the Republic was able to present in evidence in the Reivindicatoria Case several documents that were part of the records of the Expropriation Case.170 These include the Complaint dated August 15, 1938, the Order dated October 19, 1938, and the Partial Decision dated April 22, 1939.171 This means that, if the Provincial Voucher is indeed authentic and part of the Expropriation Case records, then the Republic had access to it and could have presented it during the trial in the Reivindicatoria Case had it exercised reasonable diligence. Therefore, the Provincial Voucher could not be considered as newly discovered evidence.172

The points raised by Mazy's are well-taken. The Court does not condone the observable negligence of the Republic in failing to present the Provincial Voucher in the Reivindicatoria Case despite apparently having access to the Expropriation Case records. However, in view of the Court's relaxation of the doctrine of immutability of judgments and the principle of res judicata, there would be no point in delving into whether the Provincial Voucher constitutes newly discovered evidence and whether the Republic's negligence or error in failing to present the same in the Reivindicatoria Case is binding upon it.

On hindsight, the RTC-Br. 9 (which decided the Reivindicatoria Case) or both of the parties therein could have easily had the records of the Expropriation Case subpoenaed, given that the latter pertained to a CFI branch in Cebu City and the records should have been in the archives since the Republic was able to present portions thereof. Had the entire records of the Expropriation Case been presented or made available in the Reivindicatoria Case, the Provincial Voucher would have surfaced and the claim of non payment of just compensation debunked. But the presentation of the elusive Provincial Voucher did not come to pass at that time. As will be detailed below, this Provincial Voucher has surfaced in the present proceedings. Surely, this will also have an effect on the decision in the Reivindicatoria Case, specifically on the very issue of ownership.

C. Judicial Notice

Another matter which the Court is confronted with is whether it can take judicial notice of the case records of both the Expropriation Case and the Reconstitution Case. The answer is a simple yes. Indeed, what value is there for the Court to have ordered the Executive Judge of the RTC, Cebu City to locate and take custody of the records of both the Expropriation Case and the Reconstitution Case, to keep the same secure, and to transmit them, with certified true copies, to the Court if the Court cannot take judicial notice of these records.

Rule 129, Section 1 of the Revised Rules on Evidence173 provides that mandatory judicial notice shall be taken of the official acts of the judicial department of the Philippines:

Section 1. Judicial notice, when mandatory. – A court shall take judicial notice, without the introduction of evidence, of the existence and territorial extent of states, their political history, forms of government and symbols of nationality, the law of nations, the admiralty and maritime courts of the world and their seals, the political constitution and history of the Philippines, official acts of the legislative, executive and judicial departments of the National Government of the Philippines, the laws of nature, the measure of time, and the geographical divisions.(awÞhi( (1a) (Emphasis supplied)

In Republic v. Court of Appeals,174 the Court cited this provision in ruling that courts may take judicial notice of the record of another case in another court involving one of the parties. In that case, cadastral proceedings were pending in court and a certain Josefa Gacot (Josefa) claimed an unidentified portion of the subject lot. During the proceedings, the Land Registration Authority called the attention of the cadastral court to a decision of a CFI which declared a portion of the lot to be the property of the Republic. However, the CFI decision, though presented in evidence, was not formally offered by the Republic. Thus, the cadastral court ruled in favor of Josefa. The CA affirmed the cadastral court's order, ruling that it could not take judicial notice of the CFI decision. On appeal, the Court overruled the CA and held that it should have taken judicial notice of the CFI decision. The Court thus remanded the case to the cadastral court to identify the portions being claimed by the parties and resolve their conflicting claims. Thus:

An appeal was taken by the Republic from the decision of the trial court. In its now assailed decision of 22 February 1995, the Court of Appeals affirmed in toto the judgment of the trial court. The appellate court ratiocinated:

. . . .

"It is the rule that 'The court shall consider no evidence which has not been formally offered.' (Rule 132, Sec. 34) It is true that the Order of 20 October 1950 has been appended to the records of this case (seep. 19, Rec.). But it is misleading on the part of the Solicitor General to state that 'Records of the rehearing show that on October 20, 1950, an order was, indeed, issued by Judge Lorenzo C. Garlitos ...' For, during the rehearing, as reflected in the appealed decision, the government did not present any evidence nor any memorandum despite having been ordered by the court a quo.

"Neither can We take judicial notice of the Order of Judge Garlitos. As a general rule, courts are not authorized to take judicial knowledge of the contents of the record of other cases, in the adjudication of cases pending before them, even though the trial judge in fact knows or remembers the contents thereof, or even when said other cases have been heard or are pending in the same court and notwithstanding the fact that both cases may have been heard or are really pending before the same judge. (Municipal Council vs. Colegio de San Jose, et al., G.R. No. L-45460; 31 C.J.S. 623-624; cited in p. 25 Evidence, Second Ed.; R.J. Francisco) Indeed, the Government missed its opportunity to have the claim of Josefa Gacot, the herein appellee, declared as a nullity, considering that no evidence was presented by it in opposition thereto."

....

Let it initially be said that, indeed, the Court realizes the points observed by the appellate court over which there should be no quarrel. Firstly, that the rules of procedure and jurisprudence, do not sanction the grant of evidentiary value, in ordinary trials, of evidence which is not formally offered, and secondly, that adjective law is not to be taken lightly for, without it, the enforcement of substantive law may not remain assured. The Court must add, nevertheless, that technical rules of procedure are not ends in themselves but primarily devised and designed to help in the proper and expedient dispensation of justice. In appropriate cases, therefore, the rules may have to be so construed liberally as to meet and advance the cause of substantial justice.

Furthermore, Section 1, Rule 129, of the Rules of Court provides:

"Section 1. Judicial notice, when mandatory. — A court shall take judicial notice, without the introduction of evidence, of the existence and territorial extent of states, their political history, forms of government and symbols of nationality, the law of nations, the admiralty and maritime courts of the world and their seals, the political constitution and history of the Philippines, the official acts of the legislative, executive and judicial departments of the Philippines, the laws of nature, the measure of time, and the geographical divisions."

Mr. Justice Edgardo L. Paras opined:

"A court will take judicial notice of its own acts and records in the same case, of facts established in prior proceedings in the same case, of the authenticity of its own records of another case between the same parties, of the files of related cases in the same court, and of public records on file in the same court. In addition[,] judicial notice will be taken of the record, pleadings or judgment of a case in another court between the same parties or involving one of the same parties, as well as of the record of another case between different parties in the same court. Judicial notice will also be taken of court personnel."175 (Emphasis supplied; citations omitted)

The Court also applied this principle in Clarion Printing House, Inc. v. National Labor Relations Commission.176 There, the company dismissed several of its employees citing financial losses which led it to file a petition for rehabilitation and/or liquidation or dissolution in court (Rehabilitation Case). One of the said employees assailed the validity of her dismissal. The National Labor Relations Commission ruled that the dismissal was illegal, holding that the company failed to prove the fact that it suffered financial losses. Thus, one of the issues raised before the Court in the labor case was whether the company was able to substantiate its financial losses so as to justify the dismissal of the employee. In resolving this issue, the Court took judicial notice of the records of the Rehabilitation Case which by then had already been decided with finality by the CA. The records revealed that: (1) the company filed its petition for rehabilitation before it dismissed the employee; and (2) the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) subsequently ordered the company's dissolution and liquidation. Thus:

This Court in fact takes judicial notice of the Decision of the Court of Appeals dated June 11, 2000 in CA-G.R. SP No. 55208, "Nikon Industrial Corp., Nikolite Industrial Corp., et al. [including CLARION], otherwise known as the EYCO Group of Companies v. Philippine National Bank, Solidbank Corporation, et al., collectively known and referred as the 'Consortium of Creditor Banks,'" which was elevated to this Court via Petition for Certiorari and docketed as G.R. No. 145977, but which petition this Court dismissed by Resolution dated May 3, 2005:

Considering the joint manifestation and motion to dismiss of petitioners and respondents dated February 24, 2003, stating that the parties have reached a final and comprehensive settlement of all the claims and counterclaims subject matter of the case and accordingly, agreed to the dismissal of the petition for certiorari, the Court Resolved to DISMISS the petition for certiorari (Italics supplied).

The parties in G.R. No. 145977 having sought, and this Court having granted, the dismissal of the appeal of the therein petitioners including CLARION, the CA decision which affirmed in toto the September 14, 1999 Order of the SEC, the dispositive portion of which SEC Order reads:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the appeal is as it is hereby, granted and the Order dated 18 December 1998 is set aside. The Petition to be Declared in State of Suspension of payments is hereby disapproved and the SAC Plan terminated. Consequently, all committee, conservator/receivers created pursuant to said Order are dissolved and discharged and all acts and orders issued therein are vacated.

The Commission, likewise, orders the liquidation and dissolution of the appellee corporations. The case is hereby remanded to the hearing panel below for that purpose.

. . . .

has now become final and executory. Ergo, the SEC's disapproval of the EYCO Group of Companies' "Petition for the Declaration of Suspension of Payment ..." and the order for the liquidation and dissolution of these companies including CLARION, must be deemed to have been unassailed.

That judicial notice can be taken of the above-said case of Nikon Industrial Corp., et al. v. PNB et al., there should be no doubt.

As provided in Section 1, Rule 129 of the Rules of Court:

Section 1. Judicial notice, when mandatory. — A court shall take judicial notice, without the introduction of evidence, of the existence and territorial extent of states, their political history, forms of government and symbols of nationality, the law of nations, the admiralty and maritime courts of the world and their seals, the political constitution and history of the Philippines, the official acts of the legislative, executive and judicial departments of the Philippines, the laws of nature, the measure of time, and the geographical divisions.

which Mr. Justice Edgardo L. Paras interpreted as follows:

A court will take judicial notice of its own acts and records in the same case, of facts established in prior proceedings in the same case, of the authenticity of its own records of another case between the same parties, of the files of related cases in the same court, and of public records on file in the same court. In addition[,] judicial notice will be taken of the record, pleadings or judgment of a case in another court between the same parties or involving one of the same parties, as well as of the record of another case between different parties in the same court. Judicial notice will also be taken of court personnel.

In fine, CLARION's claim that at the time it terminated Miclat it was experiencing business reverses gains more light from the SEC's disapproval of the EYCO Group of Companies' petition to be declared in state of suspension of payment, filed before Miclat's termination, and of the SEC's consequent order for the group of companies' dissolution and liquidation.177 (Emphasis supplied; citations omitted)

A notable author has also opined that the courts may take judicial notice "of proceedings in other causes because of their close connection with the matter in controversy; because 'there may be cases so closely interwoven, or so clearly interdependent, as to invoke' a rule of judicial notice in one suit [of] the proceedings in another suit."178

Pursuant to the foregoing authorities, the Court deems it proper to take judicial notice of the records of both the Expropriation Case and the Reconstitution Case.

II. Nullity of Reconstitution Case Decision and Effects

Having settled the foregoing preliminaries, the Court now proceeds to resolve the obvious issue in the Cancellation Case, which is the supposed final and binding effect of the decisions in the Reconstitution Case and the Reivindicatoria Case on the Republic.

After taking judicial notice of the records of the Reconstitution Case and upon close scrutiny thereof, the Court rules that the decision in the Reconstitution Case is void. Consequently, all proceedings founded thereon are void,179 including the decision in the Reivindicatoria Case. Being void, res judicata and immutability of judgment cannot operate in favor of both the Reconstitution and Reivindicatoria Cases.