G.R. No. 224946, November 9, 2021,

♦ Decision,

Caguioa, [J]

♦ Separate Concurring Opinion,

Perlas-Bernabe, [J]

♦ Concurring Opinion,

Leonen, [J]

♦ Concurring Opinion,

Zalameda, [J]

♦ Concurring Opinion,

M.Lopez, [J]

♦ Concurring Opinion,

Lazaro-Javier, [J]

[ G.R. No. 224946. November 09, 2021 ]

CHRISTIAN PANTONIAL ACHARON, PETITIONER, VS. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, RESPONDENT.

CONCURRING OPINION

LAZARO-JAVIER, J.:

I agree for the most part with the ponencia of the learned Justice Alfredo Benjamin S. Caguioa. I also thank him for graciously accommodating some of my views in this case, especially the relevance of the civil law on support in determining liability for violation of Section 5 (i) of Republic Act No. 9262 (RA 9262). I, nonetheless, advance the following viewpoints with the hope of providing an analytical framework for the judges of the Family Courts and designated Family Courts to work with.

The analytical framework I most respectfully suggest is not an original one. It is basically a reiteration of what first year law students have been taught when analyzing a criminal fact-pattern or case for that matter.

We start every analysis with the basic elements of the subject crime. We organize our thought process according to the established categories of actus reus and where applicable mens rea. Here, both are applicable and will be discussed to arrive at a reasoned disposition.

Why is this framework extremely important? This is because at times the statutory definition of a crime could be confusing. The analysis often begins with the elements of the crime. There is nothing wrong with that if the analysis takes full account of the legal requirement that the elements must correspond to a criminal act, conduct and/or circumstances (the actus reus) and a criminal state of mind (the mens rea). This framework is consistent with the very definition of what a crime is – actus non facit reum, nisi mens sit rea. That is, except for strict liability crimes, evil intent must unite with an unlawful act for a crime to exist.

The extreme importance of this reference to the elements of a crime is illustrated in the considered view of the esteemed Senior Associate Justice Estella M. Perlas-Bernabe that the mental or emotional suffering of the victim is not a result of the criminal act but an element of the intent in the doing of such criminal act. Senior Associate Justice Perlas-Bernabe thus rejected the formulation in Dinamling v. People1 that the third element of the offense of Section 5 (i) of RA 9262 is that the "offender causes on the woman and/or child mental or emotional anguish."

Her point of view is doubtless correct. With due respect, however, her formulation is not the entirety of the elements of Section 5 (i). She is correct that mental or emotional anguish is an integral part of the criminal state of mind (i.e., the mens rea) in the definition of Section 5 (i).

Still, Dinamling is correct too that mental or emotional anguish is also an integral part of the criminal act, conduct and/or circumstances (i.e., the actus reus) penalized by Section 5 (i). If there was no mental or emotional anguish, or if there was but it was not caused by any of the mentioned predicate criminal acts, there is no violation of Section 5 (i). So it is not entirely fruitful to eliminate, as the good Senior Associate Justice recommends, the third element of Section 5 (i) as identified in Dinamling because mental or emotional anguish is both integral parts of the mens rea (as the good Senior Associate Justice correctly observes) and the actus reus (as Dinamling rightly mentions).

Of course, the enumeration of the elements of Section 5 (i) in Dinamling is deficient because it fails to account for the mens rea component of mental or emotional anguish as properly commented by Senior Associate Justice Perlas-Bernabe. Nowhere in Dinamling was it mentioned that there must be that specific criminal intent to cause mental or emotional anguish. While Section 5 (i) is a special law, and generally crimes under a special law are erroneously lumped together as mala prohibita, it does not mean that Section 5 (i) requires no mental element. The reason is simply that the text of this provision calls for a mental element. Indeed, if the definition of a crime is not broken into its elements, and by elements, we mean the actus reus and the mens rea, we would fall into the same deficiencies as the listing of elements in Dinamling illustrates.

Hence, it is extremely important that the analytical framework in determining whether a crime has been committed by an accused and whether the prosecution has proven this crime and its commission by the accused beyond reasonable doubt, we must examine the facts if they fit into the elements of the crime charged, that is, if the facts demonstrate the commission of the actus reus and the presence of the mens rea.

The Elements of a Crime

The crimes defined in Section 5 (e) and Section 5 (i) of RA 9262 are crimes punished by a special law. But these crimes are not malum prohibitum just because they are offenses defined and punished by a special law. These crimes require as an element the presence of mens rea.

I digress a bit to quote the renowned Justice Regalado who abhorred this classification of crimes into mala in se and malum prohibitum, which I passionately shared in one2 of my opinions:

4. Nor should we hold a "judicial prejudice" from the fact that the two forms of illegal possession of firearms in Presidential Decree No. 1866 are mala prohibita. On this score, I believe it is time to disabuse our minds of some superannuated concepts of the difference between mala in se and mala prohibita. I find in these cases a felicitous occasion to point out this misperception thereon since even now there are instances of incorrect assumptions creeping into some of our decisions that if the crime is punished by the Revised Penal Code, it is necessarily a malum in se and, if provided for by a special law, it is a malum prohibitum.

It was from hornbook lore that we absorbed the distinctions given by text writers, claiming that: (1) mala in se require criminal intent on the part of the offender; in mala prohibita, the mere commission of the prohibited act, regardless of intent, is sufficient; and (2) mala in se refer to felonies in the Revised Penal Code, while mala prohibita are offenses punished under special laws.

The first distinction is still substantially correct, but the second is not accurate. In fact, even in the Revised Penal Code there are felonies which are actually and essentially mala prohibita. To illustrate, in time of war, and regardless of his intent, a person who shall have correspondence with a hostile country or territory occupied by enemy troops shall be punished therefor. An accountable public officer who voluntarily fails to issue the required receipt for any sum of money officially collected by him, regardless of his intent, is liable for illegal exaction. Unauthorized possession of picklocks or similar tools, regardless of the possessor's intent, is punishable as such illegal possession. These are felonies under the Revised Penal Code but criminal intent is not required therein.

On the other hand, I need not mention anymore that there are now in our statutes so many offenses punished under special laws but wherein criminal intent is required as an element, and which offenses are accordingly mala in se although they are not felonies provided for in the Code.3

Originally, a crime was considered to be the commission of a physical act which was specifically prohibited by law. It was the act itself which was the sole element of the crime. If it was established that the act was committed by an accused, then a finding of guilt would ensue.

As early as the twelfth century, however, in large part through the influence of the canon law, it was established that there must also be a mental element combined with the prohibited act to constitute a crime. That is to say that an accused must have meant or intended to commit the prohibited act. The physical act and the mental element which together constitute a crime came to be known as the actus reus denoting the act, and the mens rea for the mental element.

Violations of Section 5 (e) and Section 5 (i) have the requisite actus reus and mens rea elements. In deciding the merits of a criminal case, the analysis should always start from and refer to these elements and not from anywhere or to anything else.

The following excerpt from Valenzuela v. People, G.R. No. 160188, June 21, 2007, supplies the rationale for this starting point of every criminal case analysis:

The long-standing Latin maxim "actus non facit reum, nisi mens sit rea" supplies an important characteristic of a crime, that "ordinarily, evil intent must unite with an unlawful act for there to be a crime," and accordingly, there can be no crime when the criminal mind is wanting. Accepted in this jurisdiction as material in crimes mala in se, mens rea has been defined before as "a guilty mind, a guilty or wrongful purpose or criminal intent," and "essential for criminal liability." It follows that the statutory definition of our mala in se crimes must be able to supply what the mens rea of the crime is, and indeed the U.S. Supreme Court has comfortably held that "a criminal law that contains no mens rea requirement infringes on constitutionally protected rights." The criminal statute must also provide for the overt acts that constitute the crime. For a crime to exist in our legal law, it is not enough that mens rea be shown; there must also be an actus reus.

It is from the actus reus and the mens rea, as they find expression in the criminal statute, that the felony is produced. As a postulate in the craftsmanship of constitutionally sound laws, it is extremely preferable that the language of the law expressly provide when the felony is produced. Without such provision, disputes would inevitably ensue on the elemental question whether or not a crime was committed, thereby presaging the undesirable and legally dubious set-up under which the judiciary is assigned the legislative role of defining crimes. Fortunately, our Revised Penal Code does not suffer from such infirmity. From the statutory definition of any felony, a decisive passage or term is embedded which attests when the felony is produced by the acts of execution. For example, the statutory definition of murder or homicide expressly uses the phrase "shall kill another," thus making it clear that the felony is produced by the death of the victim, and conversely, it is not produced if the victim survives.

Actus reus is the act (or sometimes an omission or state of affairs) indicated in the definition of the offense charged together with (1) any consequences of that conduct which are indicated by that definition; and (2) any surrounding circumstances so indicated (other than references to the mens rea or element of negligence required on the part of the defendant, or to any defense).4

In addition to a physical element consisting of committing a prohibited act, creating a prohibited state of affairs, or omitting to do that which is required by the law, the actus reus requires the conduct in question to be willed; this is usually referred to as voluntariness. The doing of the prohibited act or conduct must involve a mental element. It is this mental element, that is the act of will, which makes the act or conduct willed or voluntary.

On the other hand, mens rea is the subjective or mental element of an accused's intention to commit a crime, or knowledge that an accused's action or lack of action would cause a crime to be committed, or willful blindness or recklessness that an accused's actus reus would cause a crime to be perpetrated.

But mens rea, properly understood, does not encompass all of the mental elements of a crime. As stated, the actus reus has its own mental element; the act must be the voluntary act of an accused for the actus reus to exist.

Mens rea, on the other hand, refers to the guilty mind, the wrongful intention, of an accused. Its function in criminal law is to prevent the conviction of the morally innocent – those who do not understand or intend the consequences of their acts.

Mens rea is a contemporaneous mental element comprising an intention to carry out the prohibited physical act or omission to act; that is to say a particular state of mind such as the intent to cause, or some foresight of, the results of the act or the state of affairs.

Thus, typically, mens rea is concerned with the mental element accompanying the consequences of the prohibited actus reus.

The prosecution always bears the burden of proving the actus reus, the mental element of voluntariness of the actus reus, and the mens rea mental element. Therefore, in certain situations, a person who committed a prohibited physical act still could not be found guilty. A number of examples come to mind.

For instance, if a person in a state of automatism as a result of a blow on the head committed a prohibited act that this person was not consciously aware of committing, the latter could not be found guilty. The mental element involved in committing a willed voluntary act and the mental element of intending to commit the act were absent. Thus neither the requisite actus reus or mens rea for the offense was present.

The result would be the same in the case of an accused who had an unexpected reaction to medication which rendered this person totally unaware of the latter's actions. Similarly, if an accused, during an epileptic seizure, with no knowledge of what this person was doing, shot and killed a victim, this accused could not be found guilty of killing since both the ability to act voluntarily and the mental element of the intention to kill were absent.

In all these instances, though the accused committed the actus reus, the latter simply could not have formed the requisite mental elements of voluntariness in the performance of the prohibited act or omission and intention to commit the prohibited act.

The statutory definition generally furnishes the elements of each crime and the elements in turn unravel the particular requisite acts of execution and accompanying criminal intent.5

The Elements of Section 5 (i) in relation to Section 3 (a) (C)

i. Actus Reus of Violation of Section 5 (i)

The starting point is the statutory definition in Section 5(i) of RA 9262:

SECTION 5. Acts of Violence Against Women and Their Children. — The crime of violence against women and their children is committed through any of the following acts....

(i) Causing mental or emotional anguish, public ridicule or humiliation to the woman or her child, including, but not limited to, repeated verbal and emotional abuse, and denial of financial support or custody of minor children or denial of access to the woman's child/children.

In relation to Section 5 (i) is Section 3 (a) (C) of RA 9262:

SECTION 3. Definition of Terms. — As used in this Act,

(a) "Violence against women and their children" refers to any act or a series of acts committed by any person against a woman who is his wife, former wife, or against a woman with whom the person has or had a sexual or dating relationship, or with whom he has a common child, or against her child whether legitimate or illegitimate, within or without the family abode, which result in or is likely to result in physical, sexual, psychological harm or suffering, or economic abuse including threats of such acts, battery, assault, coercion, harassment or arbitrary deprivation of liberty. It includes, but is not limited to, the following acts...

C. "Psychological violence" refers to acts or omissions causing or likely to cause mental or emotional suffering of the victim such as but not limited to intimidation, harassment, stalking, damage to property, public ridicule or humiliation, repeated verbal abuse and marital infidelity. It includes causing or allowing the victim to witness the physical, sexual or psychological abuse of a member of the family to which the victim belongs, or to witness pornography in any form or to witness abusive injury to pets or to unlawful or unwanted deprivation of the right to custody and/or visitation of common children.

From this definition, the actus reus of this offense consists of the –

(i) relationship between an accused and offended parties, that is, a woman with whom the person has or had a sexual or dating relationship, or with whom he has a common child, or against her child whether legitimate or illegitimate, within or without the family abode.

(ii) denial of financial support to those entitled to receive financial support and to whom an accused is obliged to give financial support.

a. The act is the deliberate withholding of the provision of financial support.

b. The consequence of the act is the absence or inadequacy of financial support as defined by law for those entitled to be supported by the accused, since the complainant cannot compensate for the support denied to the complainant and/or their children by the accused.

(iii) Legal entitlement to support and legal obligation (i.e., concurrence of capacity and need) to provide support.

(iv) Mental or emotional anguish or likelihood or probability of mental or emotional anguish on the part of those entitled to receive financial support and to whom an accused is obliged to give financial support.

(v) causation or likely causation of the mental or emotional anguish by the accused's denial of financial support.

Let me expound on each of these components of the actus reus.

(i) relationship between an accused and offended parties, that is, a woman with whom the person has or had a sexual or dating relationship, or with whom he has a common child, or against her child whether legitimate or illegitimate, within or without the family abode.

This is an objective element.

The presence of this element is not determined from a subjective (an accused's or a complainant's) perspective but from these objective or real world circumstances: (a) having a common child; (b) having engaged in a single sexual act which may or may not result in the bearing of a common child (sexual relations); or (c) having lived together without the benefit of marriage as if spouses or having been involved romantically over time and on a continuing basis during the course of their relationship, but excluding casual acquaintance or ordinary socialization between two individuals in a business or social context (dating relationship).

For purposes of establishing the actus reus, no other mental element than voluntariness has to be proved.

To clarify, it is not required that an accused or a complainant intended or was purposely involved, or knew that they were, in any of these types of relationship. It is enough that the prosecution established that they voluntarily had a child, engaged in a single sexual act, lived together as if spouses, or bonded themselves romantically continuously over a period of time.

(ii) denial of financial support to those entitled to receive financial support and to whom an accused is obliged to give financial support.

This actus reus has two components: (a) an act and (b) a consequence.

The act, as correctly defined by Justice Caguioa, is the deliberate withholding of the provision of financial support.

The consequence thereof is the absence or inadequacy of financial support as defined by law (i.e., Article 194, Family Code: "Support comprises everything indispensable for sustenance, dwelling, clothing, medical attendance, education and transportation, in keeping with the financial capacity of the family") for those entitled to be supported by the accused, since the complainant cannot compensate for the support denied to the complainant and/or their children by the accused.

The test in establishing this actus reus is objective.

The presence of this element is not determined from a subjective (an accused's or a complainant's) perspective but from objective or real world circumstances.

The relevant objective circumstances to establish this actus reus include:

- subject-matter of the needed sustenance, dwelling, clothing, medical attendance, education and transportation;

- amounts required to pay for the foregoing support items;

- the claimed support items vis-à-vis the financial capacity of the family prior to the withholding of the provision of financial support;

- demand to an accused to pay financial support;

- capacity of an accused to give support;

- non-provision or partial provision of financial support; and

- absent or inadequate financial support on the part of the obligees of the support since the woman is unable to compensate for the denied support by the accused.

Notably, there is a legal obligation to provide support only if there is a concurrence between the capacity to give support and the need to be supported. If there is no such legal obligation, there can be no actus reus of deliberately withholding financial support because there is really nothing to withhold. Also, if there is no legal obligation to give support, the act of denying financial support cannot be a criminal act since there is no legal mandate to do so.

There are two legitimate issues on this actus reus:

(a) whether the act component of the actus reus of denial of financial support refers to the denial of full or partial financial support.

Hence, if an accused, during the period alleged in the Information, provided some support for a portion or the entirety of this period, would he still be liable for violation of Section 5 (i)?

My short answer to this issue is that the quantum of support denied by an accused is not material. This is because the language of the statute does not make such distinction.

Further, the purpose of the law is to redress a complainant's mental or emotional anguish and deter others from causing it. The proposed distinction should not be allowed because a denial of either a full or partial support could still potentially result in such prejudice.

(b) whether the actus reus of denial of financial support has really a consequence component, that is, the act of denial of support should result in the absence or inadequacy of financial support to those entitled to be supported, that is, the financial support to the woman and/or the children would be absent or at least insufficient as a result of the accused's denial of support.

Or, whether it is enough that an accused denied support regardless of the consequence or impact of the denial of support.

As already mentioned above, this actus reus has both an act and consequence components. The act of denial of support must have the consequence of depriving the woman and/or their children in whole or in part of the needed support as the woman is unable to compensate for the accused's denied support.

Therefore, if the woman is able to provide the needed support for herself and/or their children, and the accused's denial of support has no prejudicial impact upon the obligees' support, then there is no violation of Section 5 (i) of RA 9262, even if the woman is mentally or emotionally anguished by the accused's apparent finagling of the woman in terms of not sharing in the support obligations.

The rationale for the consequence component of this actus reus is the policy behind RA 9262.

Section 2 states that the statute is designed to value the dignity of women and children, to guarantee full respect for their human rights, to recognize the need to protect women and children from violence and threats to their personal safety and security.

If the woman is able to provide adequate financial support to herself and/or the children sans the accused's financial support, the policy behind RA 9262 is not at all implicated.

This is because, if the woman and the children are financially secure despite the accused's denial of financial support, there is no impairment of their dignity or violation of their human rights or their personal security. The woman's remedy in this instance is not under RA 9262 but under the civil laws on support as well as her access to and liquidation and dissolution of their property relations if any.

Another rationale is that the legal obligation to give financial support entails the concurrence of the capacity to provide financial support and the need to be supported. If there is no legal obligation to give financial support, the act of denying financial support cannot be a criminal act because there is no legal compulsion to extend financial support.

This actus reus of denial of support has two mental elements – the voluntary mental element of the actus reus and the mens rea mental element.

The mens rea element will be discussed below.

As regards the voluntariness of the act, this means the prosecution has to establish that the accused was not forced to deny financial support due to lack of resources, other legal obligations and other circumstances beyond the accused's control or discretion preventing the accused from providing financial support.

(iii) Legal entitlement to support and legal obligation (i.e., concurrence of capacity and need) to provide support

This actus reus is an objective element. This is determined by the civil laws on support. Neither an accused nor a complainant can determine for themselves who is entitled to support and who is obliged to give support. The civil laws provide the answer. Accordingly, the legal obligation to provide support requires the concurrence of an accused's capacity to provide support and an obligee's need for support.

(iv) Mental or emotional anguish or likelihood or probability of mental or emotional anguish itself, on the part of those entitled to receive financial support and to whom an accused is obliged to give financial support.

This actus reus has both subjective and objective components.

Mental or emotional anguish is subjective if the woman and/or her children with the accused has/have attested to its existence, that is, they testify that they are in fact suffering from mental or emotional anguish.

As held in Dinamling v. People, 761 Phil. 356 (2015), this is element is proven by the testimonies of the complainant woman and/or children since the mental or emotional anguish is personal to them.

If the complainants testify to this effect, they have established halfway this actus reus. The other half is determined by the credibility of this claim that must then be examined on the totality of the evidence in the case.

Mental or emotional anguish is objective if the claim is limited to the likelihood or probability of mental or emotional anguish of the woman and/or her children with the accused. To be liable for violation of Section 5 (i), among other requisites, the mental or emotional anguish need not exist as a fact but there must at least be the likelihood or probability of its occurrence according to the perspective of reasonable persons in the situation of the woman and/or her children.

Note that this actus reus of the likelihood or probability of mental or emotional anguish is found textually in Section 3 (a) (C) of RA 9262 and not in the text of Section 5 (i). Nonetheless, since Section 5 (i) must be read in relation to Section 3 (a) (C), this particular component of the actus reus is deemed written into the statutory definition of the crime under Section 5 (i).

(v) causation or likely causation of the mental or emotional anguish by the accused's denial of financial support.

This actus reus has both subjective and objective components.

The causation of mental or emotional anguish by the accused's denial of financial support is subjective if the woman and/or her children with the accused has/have attested to the existence of this causation, that is, they testify that they are in fact suffering from mental or emotional anguish as a result of the accused's denial of financial support.

If the complainants testify to this effect, they have established halfway this actus reus. The other half is determined by the credibility of this claim that must then be examined on the totality of the evidence in the case.

This causation of the mental or emotional anguish is objective if the claim is limited to the likelihood or probability of the causation of mental or emotional anguish by the accused's denial of financial support.

Causation need not exist as a fact but there must at least be the likelihood or probability of this causation according to the perspective of reasonable persons in the situation of the woman and/or her children.

The causal relationship required by the law is that the mental or emotional anguish need not only be factual or consummated by the accused's denial of support but also be likely or probable to happen as a result of the denial of financial support.

This actus reus of the likelihood or probability of the causation of mental or emotional anguish is found textually in Section 3 (a) (C) of RA 9262 and not in the text of Section 5 (i). Nonetheless, since Section 5 (i) must be read in relation to Section 3 (a) (C), this specific actus reus is deemed written into the statutory definition of the crime under Section 5 (i).

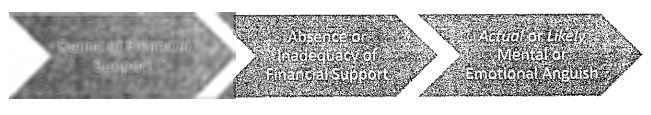

Notably, the actus reus of denial of financial support has both act and consequence components. The emotional or mental anguish must be caused by the ultimate consequence of the denial of financial support, which is the absence or inadequacy of support that cannot be compensated by the woman's own resources. This connection among these components of the actus reus may be illustrated as follows:

Conversely, if the mental or emotional anguish is not due to or likely to be due to the absence or inadequacy of support, since the woman is able to provide ample support or since the woman is bothered by something else, then Section 5 (i) is not the proper remedy for the woman and/or their children.

There is a mental element to this actus reus but this is found in the mens rea element of Section 5 (i) – the accused's intention and purpose to inflict such mental or emotional anguish upon the woman and/or their children or the willful blindness or recklessness of the accused's conduct in not recognizing that the act of denying financial support would probably or likely cause such mental or emotional anguish on their part.

ii. Mens rea of Violation of Section 5 (i)

While RA 9262 defines an offense punishable by a special law, violation of Section 5 (i) in relation to Section 3 (a) (C) nonetheless requires a mens rea element.

The mens rea has three components:

(i) the specific intent of an accused to deny financial support to the obligees of support, which requires as stated the mental element of voluntary performance of this act and the intention, purpose and knowledge to do so.

(ii) the specific intent of an accused to cause the absence or inadequacy of financial support on the part of the obligees of support, which requires not only the mental element of voluntary performance of the act of denying financial support but also the intention, purpose and knowledge to accomplish such consequence of the act of denying support; the absence or inadequacy of financial support on the part of the obligees of support must be a fact – they must in fact be in need of the accused's financial support,

(iii) the specific intent to cause or to likely cause the obligees' mental or emotional anguish due to the accused's denial of financial support and its consequence of absence or inadequacy of financial support.

Note that the third specific intent requirement of to cause likely is found textually in Section 3 (a) (C) of RA 9262 and not in the text of Section 5 (i). But since Section 5 (i) must be read in relation to Section 3 (a) (C), this specific intent is deemed written into the statutory definition of the crime under Section 5 (i).

This mental element consists of the accused's intention and purpose to cause or inflict such mental or emotional anguish upon the woman and/or their children by denying them financial support. This is the mental element required where mental or emotional anguish is actually suffered by them.

Alternatively, the mental element may also be the accused's willful blindness or recklessness in pursuing the act of denying financial support and not recognizing that this act would probably or likely cause such mental or emotional anguish on the woman and/or their children.

Application of the Elements of Section 5 (i) in relation to Section 3 (a) (C)

i. Facts of the Case

Accused-petitioner was charged with violation of Section 5 (i) of RA 9262 in an Information alleging thus:

That sometime in (sic) January 25, 2012, up to the present, in Valenzuela City and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the above-named accused, did then and there willfully, unlawfully and feloniously cause mental or emotional anguish, public ridicule or humiliation to his wife AAA, by denying financial support to the said complainant.

He pleaded not guilty to the charge and trial ensued. According to the trial court, after he left for Brunei to work as an overseas worker, he maintained another romantic non-marital relationship while not being emotionally separated from his spouse. The latter is the sole complainant in this criminal case as she and accused had no children. In Brunei, he lived together with the woman. He also failed to pay the amount he and his spouse had borrowed to settle his placement fee. As recounted by the trial court:

However, the accused did not send money on a regular basis. All in all, he was able to send money in the total amount of P71,500.00 only, leaving the balance in the amount of P13,500.00. For which reason, she felt so embarrassed with [their creditor] because she could not pay the balance. She even pleaded to [their creditor] not to lodge a complaint to the barangay. [Their creditor] communicated to the employer of the accused in Brunei about their debt to her.

....

On cross, she stated that when the accused left in December 2011, she [was] jobless. Presently, she is gainfully employed. She lost communication with the accused since January 2012. According to the employer and friends of the accused, the latter is living with his paramour in Brunei. She filed this case because she was extremely hurt and she experience emotional agony by the neglect and utter insensitivity that the accused made her endure and suffer.

Accused-petitioner explained that he really wanted to send and bring money back from Brunei. Unfortunately, while he was in Brunei, his rented place was razed by fire and he met a vehicular accident which required him to spend a significant sum of money. He and his spouse had an on and off communication from October 2011 until April 2013. He admitted though that complainant demanded that he pay the entire amount of the debt.

He further recalled:

He used to send money to the private complainant. But it was the latter who told him not to send money anymore. He also claimed that he was able to send the total amount of P71,000.00 to the private complainant in payment of their loan. He agreed that the same is not enough to fully pay their loan in the total amount of P85,000.00.

ii. Application of the Analytical Test to the Facts of the Case

I agree with the ponencia that accused-petitioner is entitled to an acquittal.

The prosecution failed to prove at all the requisite actus reus and necessarily mens rea of Section 5 (i).

The following components of the actus reus are not disputed:

(i) relationship between an accused and offended parties, that is, a woman with whom the person has or had a sexual or dating relationship, or with whom he has a common child, or against her child whether legitimate or illegitimate, within or without the family abode.

(ii) Legal entitlement to support and legal obligation (i.e., concurrence of capacity and need) to provide support

(iii) Mental or emotional anguish or likelihood or probability of mental or emotional anguish on the part of those entitled to receive financial support and to whom an accused is obliged to give financial support.

At issue are these components of actus reus:

(i) denial of financial support to those entitled to receive financial support and to whom an accused is obliged to give financial support.

a.The act is the deliberate withholding of the provision of financial support.

b.The consequence of the act is the absence or inadequacy of financial support as defined by law for those entitled to be supported by the accused, since the complainant cannot compensate for the support denied to the complainant and/or their children by the accused.

(ii) The consequence or likely consequence of mental or emotional anguish as a result of the accused's denial of financial support

There was no deliberate withholding of financial support because –

(a) the unfortunate events in accused-petitioner's life in Brunei prevented him from saving money that he could have remitted to the Philippines; with no money to remit, there was nothing he was withholding much less deliberately withholding; and

(b) there was no demand from his spouse to provide support; if there was no demand to give support, it cannot be said that he was deliberately withholding or in short denying financial support.

His spouse also did not suffer absent or inadequate support. She was gainfully employed as she had admitted. She also did not demand support at all. All she wanted was for him to pay his debt to their godmother.

Thus, the consequence of the act component – absent or inadequate support is also missing.

While complainant suffered emotional or mental anguish, this was not the result of any denial of financial support (which did not happen anyway) or the absence or inadequacy of financial support (which did not occur too).

Rather, the emotional or mental anguish was due to the alleged other relationship of accused-petitioner. This cause of the mental or emotional anguish, however, was not the mode of psychological violence alleged in the Information. It should not and could not have been, therefore, the proof-focus of the prosecution evidence against him. This allegation, though harrowing to complainant, is not the cause of the accusation, hence, it is irrelevant and inadmissible in this case.

Since the actus reus of the crime charged was not proved at all, any discussion on its mens rea element is totally unnecessary. The reason is that there is no prohibited act, state of affairs, and consequence to which the relevant mens rea could attach.

iii. Criminalization of Non-Provision of Support and the Variance Doctrine

RA 9262 does not criminalize the mere omission to pay support or solely the non-provision of support. The matter of support as an item of the actus reus appears only in Section 5 (i) in relation to Section 3 (a) (C) and Section 5 (e) (2). In both these provisions, lack of support or provision of inadequate support is criminal only if the other components of the statutorily defined actus reus and mens rea are present.

Neither does RA 9262 criminalize the mere denial of financial support.

In particular, I agree with Justice Caguioa that Melgar v. People, G.R. No. 223477, February 14, 2018, imprecisely held that Section 5 (i) necessarily includes Section 5 (e) (2) and that this actus reus can be the sole basis for a conviction under Section 5 (e) (2).

Justice Caguioa also correctly recommended abandoning this case law and Reyes v. People, G.R. No. 232678, July 3, 2019, which affirmed Melgar.

Section 5 (e) (2) is not necessarily included in Section 5 (i) because the element of the former is not only denial of financial support.

But for the element of depriving or threatening to deprive the woman or her children of financial support legally due her or her family, or deliberately providing the woman's children insufficient financial support, which is a common element with Section 5 (i), the statutory definition of Section 5 (e) (2) requires different actus reus and mens rea.

Without exhaustively canvassing the elements of Section 5 (e) (2), the actus reus includes the overarching prohibited consequence of controlling or restricting, attempting to control or restrict, or threatening to control or restrict, the woman's or her child's movement or conduct. This is not an element of Section 5 (i) and is a distinctive element of the crime loosely termed economic abuse.

Further, the mens rea of Section 5 (e) (2) includes the specific intent to bring about or cause – the intentional, purposeful and knowing bringing about or causing of – the overarching prohibited consequence. This specific intent is not present in Section 5 (i) and is a distinctive element of Section 5 (e) (2).

The cause of accusation for Section 5 (e) (2) crime is different from the cause of accusation under Section 5 (i). Each of these elements must be alleged in the Information and proven beyond a reasonable doubt to obtain a conviction.

Allegations for Section 5 (i) do not encompass allegations under Section 5 (e) (2) because the former are different from the latter.

The variance principle was therefore inaccurately applied in Melgar and Reyes. The good Senior Associate Justice graciously conceded this point in her Reflections and, for this and other reasons, I admire and respect superbly her wisdom, graciousness, and humility.

iv. Opinion of Senior Associate Justice Perlas-Bernabe

I agree with the good Senior Associate Justice that Section 3 (a) has a bearing upon the meaning of the particular criminal provision in RA 9262, Section 5. I myself refer to Section 3 (a) to identify the act and consequence and the mental elements of Section 5. The Supreme Court has in fact done so countless times prior.

I respectfully suggest, however, that Section 3 (a) is not just about the effects of the acts mentioned in Section 5 upon the woman and/or her children.6

Section 3 (a) is far more comprehensive than what the good Senior Associate Justice proffers. Please consider the following:

Section 5 (i) punishes the infliction of mental or emotional anguish by means of the acts some of which are mentioned in Section 5 (i) while others are stated in Section 3 (a) (C).

An example is marital infidelity which appears in the latter but not in Section 5 (i). Denial of financial support is mentioned in Section 5 (i) but not in Section 3 (a) (C).

Section 5 (i) requires the mens rea of the specific intent to cause mental or emotional anguish. It is a specific intent because the mere voluntary performance or omission of denial of financial support does not automatically result in the actus reus of mental or emotional anguish. The latter effect must be specifically willed or intended.

But Section 3 (a) (C) adds another dimension of actus reus and mens rea – likely to cause mental or emotional anguish.

Denial of financial support that is likely to cause emotional or mental anguish is an actus reus that is different and apart from denial of financial support that causes mental or emotional anguish. This actus reus has a different mental component as mens rea. Likely to cause calls for the mental states of willful blindness or recklessness and not intent, purpose or knowledge.

I also humbly opine that the mental element in mens rea is not the intent to commit psychological violence or economic abuse.7 I think, as the good Senior Associate Justice does, that this is an imprecise way of identifying the mens rea of Section 5 (i) in relation to Section 3 (a) (C).

The mental element in mens rea must be correlated to the specific actus reus component to which the mental element attaches.

The terms psychological violence and economic abuse, for instance, are a bundle of components of the actus reus and the mens rea, some of which intersect between these types of violence, some are shared between them, and some are distinctive. So we have to be more specific and precise when identifying the actus reus and mens rea involved.

Thus, I agree with the view of Senior Associate Justice Perlas-Bernabe that

Therefore, since it has been established that the types of violence are neither exclusive to a Section 5 act nor are the means/punishable offense, it is but proper to situate intent on the actual purposes mentioned in Section 5 of RA 9262. These purposes are in the nature of specific intent, which must underlie the commission of the act sought to be punished.

Still, I do not think it was error for Justice Caguioa to categorize the provisions of Section 5 into the types of violence identified and defined or illustrated in Section 3 (a). I agree with the following approach of Justice Caguioa to which Senior Justice Perlas-Bernabe disagreed –

A simple reading of Section 5 reveals that it is meant to classify the acts of violence against women already identified and defined under Section 3. Sections 5 (a) to 5 (d) seek to protect women and their children from physical violence, 5 (f), 5 (h) and 5 (i) from psychological violence, and 5 (g) from physical and sexual violence. Meanwhile, Section 5 (e), as previously discussed, protects the woman from acts of violence that are committed for the purpose of attempting to control her conduct or actions, or make her lose her agency. To the mind of the Court, Section 5 (e) enumerates the act of "economic abuse" defined under Section 3.

This approach commends itself to a more organized and simplified understanding of the elements of the Section 5 offenses in relation to the types of offenses classified in Section 3 (a) (C). While there might be some divergence between the types of offense categorized in Section 3 (a) and the definition of the offenses in Section 5, there is a general correspondence in the coupling or pairing made by Justice Caguioa. The approach may not be perfect but it is a shorthand reference to what is relevant in Section 3 (a) vis-à-vis Section 5. But of course Senior Associate Justice Perlas-Bernabe is correct in advising caution in using these pairings when they are not on-all-fours with the specifics of an actual case.

I appreciate her opinion that here, the specific intent requirement is as follows:

Instead of stating that the prosecution must show that the accused intended to commit psychological violence, it is submitted that the more accurate phrasing is that the prosecution must prove that the accused, by depriving AAA, his wife, of financial support, intended to cause her mental or emotional anguish, public ridicule or humiliation, which thereby resulted into psychological violence.

She also mentions that –

Overall, I respectfully submit that it is necessary to frame the specific intent not relative to the form of violence alleged to have resulted, but rather to the actual purposes mentioned in the acts stated in Section 5 itself.

I believe that her formulation is in synch with my discussion above on the specific intent mens rea, to wit:

(iv) the specific intent of an accused to deny financial support to the obligees of support, which requires as stated the mental element of voluntary performance of this act and the intention, purpose and knowledge to do so.

(v) the specific intent of an accused to cause the absence or inadequacy of financial support on the part of the obligees of support, which requires not only the mental element of voluntary performance of the act of denying financial support but also the intention, purpose and knowledge to accomplish such consequence of the act of denying support; the absence or inadequacy of financial support on the part of the obligees of support must be a fact – they must in fact be in need of the accused's financial support,

(vi) the specific intent to cause or to likely cause the obligees' mental or emotional anguish due to the accused's denial of financial support and its consequence of absence or inadequacy of financial support.

To be sure, the key to analyzing criminal statutes and cases is –

(1) to examine the elements of the crime by using the categories of actus reus and mens rea, and then,

(2) to determine the actual components of these elements from the statutory definition of the crime itself and the purpose for the enactment of the criminal provision.

This analysis could be a painstaking one but it should able to account for the policies behind the criminal statute.

Conclusion

ALL TOLD, I concur in the result and vote to grant the petition and acquit accused-petitioner of violation of Section 5 (i) of RA 9262 or of any other crime necessarily included therein if any.

Footnotes

1 761 Phil. 356, 374 (2015).

2 Sama v. People, G.R. No. 224469, January 5, 2021.

3 Concurring Opinion, People v. Quejada, 328 Phil. 505 (1996).

4 Criminal Law (Volume 25 (2020), paras 1-552; Volume 26 (2020), paras 553-1014) Commentary at https://www.lexisnexis.co.uk/legal/commentary/halsburys-laws-of-england/criminal-law/the-actus-reus.

5 Valenzuela v. People, supra.

6 The learned Senior Associate Justice opined during the deliberation that "[a]ccordingly, the Court would do well to clarify the perception in some earlier cases wherein the types of violence under Section 3 (a) of RA 9262 as means/punishable offenses. At the risk of belaboring the point, these types of violence are only descriptive of the effects on the woman and her child which result from the specific acts committed by the accused listed in Section 5 of RA 9262. Simply put, the acts enumerated in Section 5 are the means/punishable offenses, while the types of violence in Section 3 (a) -physical, sexual, and psychological violence and economic abuse - are the ends/resulting effects.

7 The good Senior Associate Justice mentioned that "[t]he above-discussed conceptual nuances are relevant since it affects the determination on where to situate criminal intent. In my opinion, considering that (1) the punishable acts are those provided under Section 5 of RA 9262; and (2) that the types of violence under Section 3 (a) are the resultant effects on the part of the woman or her child, it is thus inaccurate to say that the prosecution must show, by proof beyond reasonable doubt, that "the accused had the intent to inflict [for example] psychological violence to the woman x x x".

The Lawphil Project - Arellano Law Foundation