G.R. No. 227363, March 12, 2019,

♦ Decision,

Peralta, [J]

♦ Separate Opinion,

Perlas Bernabe, [J]

♦ Separate Concurring Opinion,

Leonen, [J]

♦ Concurring and Dissenting Opinion,

Caguioa, [J]

[ G.R. No. 227363. March 12, 2019 ]

PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, PLAINTIFF-APPELLEE, VS. SALVADOR TULAGAN, ACCUSED-APPELLANT.

CONCURRING AND DISSENTING OPINION

CAGUIOA, J.:

I concur partly in the result, but express my disagreement with some pronouncements in the ponencia.

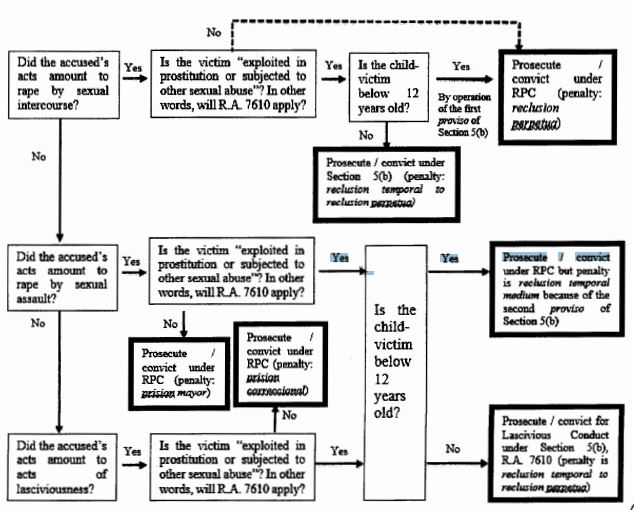

My view of the relevant laws and their respective applications is straightforward and simple: apply Section 5(b) of Republic Act No. (R.A.) 7610 upon the concurrence of both allegation and proof that the victim is "exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse," and in its absence — or in all other cases — apply the provisions of the Revised Penal Code (RPC), as amended by R.A. 8353. To illustrate the simplicity of my position, which I argue is the correct interpretation of the foregoing laws, I took the liberty of presenting it using the flowchart below:

The ponencia attempts at length to reconcile, for the guidance of the Bench and the Bar, the provisions on Acts of Lasciviousness, Rape and Sexual Assault under the RPC, as amended by R.A. 8353, and the provisions on Sexual Intercourse and Lascivious Conduct under Section 5(b) of R.A. 7610. In the ponencia, the following matrix1 is put forth regarding the designation or nomenclature of the crimes and the corresponding imposable penalties, depending on the age and circumstances of the victim:

| Crime Committed: |

Victim is under 12 years old or demented |

Victim is 12 years old or older but below 18, or is 18 years old but under special circumstances2 |

Victim is 18 years old and above |

| Acts of Lasciviousness committed against children exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse |

Acts of Lasciviousness under Article 336 of the RPC in relation to Section 5(b) of R.A. No. 7610: reclusion temporal in its medium period |

Lascivious conduct under Section 5(b) of R.A. No. 7610: reclusion temporal in its medium period to reclusion perpetua |

Not applicable |

| Sexual Assault committed against children exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse |

Sexual Assault under Article 266-A(2) of the RPC in relation to Section 5(b) of R.A. No. 7610: reclusion temporal in its medium period |

Lascivious Conduct under Section 5(b) of R.A. No. 7610: reclusion temporal in its medium period to reclusion perpetua |

Not applicable |

| Sexual Intercourse committed against children exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse |

Rape under Article 266-A(1) of the RPC: reclusion perpetua, except when the victim is below 7 years old in which case death penalty shall be imposed |

Sexual Abuse under Section 5(b) of R.A. No. 7610: reclusion temporal in its medium period to reclusion perpetua |

Not applicable |

| Rape by carnal knowledge |

Rape under Article 266-A(1) in relation to Art. 266-B of the RPC: reclusion perpetua, except when the victim is below 7 years old in which case death penalty shall be imposed |

Rape under Article 266-A(1) in relation to Art. 266-B of the RPC: reclusion perpetua |

Rape under Article 266-A(1) of the RPC: reclusion perpetua |

| Rape by Sexual Assault |

Sexual Assault under Article 266-A(2) of the RPC in relation to Section 5(b) of R.A. No. 7610: reclusion temporal in its medium period |

Lascivious Conduct under Section 5(b) of R.A. No. 7610: reclusion temporal in its medium period to reclusion perpetua |

Sexual Assault under Article 266-A(2) of the RPC: prision mayor |

The above table is recommended by the ponencia in recognition of the fact that the current state of jurisprudence on the matter is confusing.

I salute this laudable objective of the ponencia.

However, I submit that the said objective could be better achieved by re-examining the landmark cases on the matter, namely the cases of Dimakuta v. People3 (Dimakuta), Quimvel v. People4 (Quimvel), and People v. Caoili5 (Caoili) and recognizing that these were based on misplaced premises.

For one, the rulings in the aforementioned cases were based on the mistaken notion that it is necessary to apply R.A. 7610 to all cases where a child is subjected to sexual abuse because of the higher penalties therein; that is, there was always a need to look at the highest penalty provided by the different laws, and apply the law with the highest penalty because this would then be in line with the State policy "to provide special protection to children from all forms of abuse, neglect, cruelty, exploitation and discrimination, and other conditions prejudicial to their development."6 This way of thinking was first implemented in Dimakuta where the Court held:

Article 226-A, paragraph 2 of the RPC, punishes inserting of the penis into another person's mouth or anal orifice, or any instrument or object, into the genital or anal orifice of another person if the victim did not consent either it was done through force, threat or intimidation; or when the victim is deprived of reason or is otherwise unconscious; or by means of fraudulent machination or grave abuse of authority as sexual assault as a form of rape. However, in instances where the lascivious conduct is covered by the definition under R.A. No. 7610, where the penalty is reclusion temporal medium, and the act is likewise covered by sexual assault under Article 266-A, paragraph 2 of the RPC, which is punishable by prision mayor, the offender should be liable for violation of Section 5(b), Article III of R.A. No. 7610, where the law provides for the higher penalty of reclusion temporal medium, if the offended party is a child victim. But if the victim is at least eighteen (18) years of age, the offender should be liable under Art. 266-A, par. 2 of the RPC and not R.A. No. 7610, unless the victim is at least eighteen (18) years and she is unable to fully take care of herself or protect herself from abuse, neglect, cruelty, exploitation or discrimination because of a physical or mental disability or condition, in which case, the offender may still be held liable for sexual abuse under R.A. No. 7610.

There could be no other conclusion, a child is presumed by law to be incapable of giving rational consent to any lascivious act, taking into account the constitutionally enshrined State policy to promote the physical, moral, spiritual, intellectual and social well-being of the youth, as well as, in harmony with the foremost consideration of the child's best interests in all actions concerning him or her. This is equally consistent with the declared policy of the State to provide special protection to children from all forms of abuse, neglect, cruelty, exploitation and discrimination, and other conditions prejudicial to their development; provide sanctions for their commission and carry out a program for prevention and deterrence of and crisis intervention in situations of child abuse, exploitation, and discrimination. Besides, if it was the intention of the framers of the law to make child offenders liable only of Article 266-A of the RPC, which provides for a lower penalty than R.A. No. 7610, the law could have expressly made such statements.7 (Additional emphasis and underscoring supplied)

This premise, which I believe should be revisited, was based on another premise, which I also believe to be erroneous and should likewise be revisited: that R.A. 7610 was enacted to cover any and all types of sexual abuse committed against children.

Focusing first on R.A. 7610, I ask the Court to consider anew the viewpoint I first put forth in my Separate Dissenting Opinion in Quimvel, that the provisions of R.A. 7610 should be understood in their proper context, i.e., that they apply only to the specific and limited instances where the victim is a child "exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse."

Foremost rule in construing a statute is verba legis; thus, when a statute is clear and free from ambiguity, it must be given its literal meaning and applied without attempted interpretation

As I stated in my dissent in Quimvel, if the intention of R.A. 7610 is to penalize all sexual abuses against children under its provisions to the exclusion of the RPC, it would have expressly stated so and would have done away with the qualification that the child be "exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse." Indeed, it bears to stress that when the statute speaks unequivocally, there is nothing for the courts to do but to apply it: meaning, Section 5(b), R.A. 7610 is a provision of specific and limited application, and must be applied as worded — a separate and distinct offense from the "common" or "ordinary" acts of lasciviousness under Article 336 of the RPC.8

The ponencia reasons that "when there is an absurdity in the interpretation of the provisions of the law, the proper recourse is to refer to the objectives or the declaration of state policy and principles"9 under the law in question.

While I agree that the overall objectives of the law or its declaration of state policies may be consulted in ascertaining the meaning and applicability of its provisions, it must be emphasized that there is no room for statutory construction when the letter of the law is clear. Otherwise stated, a condition sine qua non before the court may construe or interpret a statute is that there be doubt or ambiguity in its language.10 In this case, Section 5(b) of R.A. 7610 states:

SEC. 5. Child Prostitution and Other Sexual Abuse. - x x x

The penalty of reclusion temporal in its medium period to reclusion perpetua shall be imposed upon the following:

x x x x

(b) Those who commit the act of sexual intercourse or lascivious conduct with a child exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse; Provided, That when the victim is under twelve (12) years of age, the perpetrators shall be prosecuted under Article 335, paragraph 3, for rape and Article 336 of Act No. 3815, as amended, the Revised Penal Code, for rape or lascivious conduct, as the case may be: Provided, That the penalty for lascivious conduct when the victim is under twelve (12) years of age shall be reclusion temporal in its medium period[.] (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

The letter of Section 5(b), R.A. 7610 is clear: it only punishes those who commit the act of sexual intercourse or lascivious conduct with a child exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse. There is no ambiguity to speak of that necessitates the Court's exercise of statutory construction to ascertain the legislature's intent in enacting the law.

Verily, the legislative intent is already made manifest in the letter of the law which, again, states that the person to be punished by Section 5(b) is the one who committed the act of sexual intercourse or lascivious conduct with a child exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse (or what Justice Estela M. Perlas-Bernabe calls as EPSOSA, for brevity).

Even with the application of the aids to statutory construction, the Court would still arrive at the same conclusion

The ponencia disagrees, and asserts that "[c]ontrary to the view of Justice Caguioa, Section 5(b), Article III of R.A. No. 7610 is not as clear as it appears to be".11 This admission alone should have ended the discussion, consistent with the fundamental established principle that penal laws are strictly construed against the State and liberally in favor of the accused, and that any reasonable doubt must be resolved in favor of the accused.12

In addition, even if it is conceded, for the sake of argument, that there is room for statutory construction, the same conclusion would still be reached.

Expressio unius est exclusio alterius. Where a statute, by its terms, is expressly limited to certain matters, it may not, by interpretation or construction, be extended to others.13 The rule proceeds from the premise that the legislature would not have made specified enumerations in a statute had the intention been not to restrict its meaning and to confine its terms to those expressly mentioned.14 In the present case, if the legislature intended for Section 5(b), R.A. 7610 to cover any and all types of sexual abuse committed against children, then why would it bother adding language to the effect that the provision applies to "children exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse"? Relevantly, why would it also put Section 5 under Article III of the law, which is entitled "Child Prostitution and Other Sexual Abuse"?

A closer scrutiny of the structure of Section 5 of R.A. 7610 further demonstrates its intended application: to cover only cases of prostitution, or other related sexual abuse akin to prostitution but may or may not be for consideration or profit. In my considered opinion, the structure of Section 5 follows the more common model or progression of child prostitution or other forms of sexual exploitation. The entire Section 5 of R.A. 7610 provides:

SEC. 5. Child Prostitution and Other Sexual Abuse. — Children, whether male or female, who for money, profit, or any other consideration or due to the coercion or influence of any adult, syndicate or group, indulge in sexual intercourse or lascivious conduct, are deemed to be children exploited in prostitution and other sexual abuse.

The penalty of reclusion temporal in its medium period to reclusion perpetua shall be imposed upon the following:

(a) Those who engage in or promote, facilitate or induce child prostitution which include, but are not limited to, the following:

(1) Acting as a procurer of a child prostitute;

(2) Inducing a person to be a client of a child prostitute by means of written or oral advertisements or other similar means;

(3) Taking advantage of influence or relationship to procure a child as prostitute;

(4) Threatening or using violence towards a child to engage him as a prostitute; or

(5) Giving monetary consideration, goods or other pecuniary benefit to a child with intent to engage such child in prostitution.

(b) Those who commit the act of sexual intercourse or lascivious conduct with a child exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse: Provided, That when the victim is under twelve (12) years of age, the perpetrators shall be prosecuted under Article 335, paragraph 3, for rape and Article 336 of Act No. 3815, as amended, the Revised Penal Code, for rape or lascivious conduct, as the case may be: Provided, That the penalty for lascivious conduct when the victim is under twelve (12) years of age shall be reclusion temporal in its medium period; and

(c) Those who derive profit or advantage therefrom, whether as manager or owner of the establishment where the prostitution takes place, or of the sauna, disco, bar, resort, place of entertainment or establishment serving as a cover or which engages in prostitution in addition to the activity for which the license has been issued to said establishment.

From the above, it is clear that Section 5(a) punishes the procurer of the services of the child, or in layman's parlance, the pimp. Section 5(b), in turn, punishes the person who himself (or herself) commits the sexual abuse on the child. Section 5(c) finally then punishes any other person who derives profit or advantage therefrom, such as, but are not limited to, owners of establishments where the sexual abuse is committed.

This is the reason why I stated in my opinion in Quimvel that no requirement of a prior sexual affront is required to be charged and convicted under Section 5(b) of R.A. 7610. Here, the person who has sexual intercourse or performs lascivious acts upon the child, even if this were the very first act by the child, already makes the person liable under Section 5(b), because the very fact that someone had procured the child to be used for another person's sexual gratification in exchange for money, profit or other consideration already qualifies the child as a child exploited in prostitution.

Thus, in cases where any person, under the circumstances of Section 5(a), procures, induces, or threatens a child to engage in any sexual activity with another person, even without an allegation or showing that the impetus is money, profit or other consideration, the first sexual affront by the person to whom the child is offered already triggers Section 5(b) because the circumstance of the child being offered to another already qualifies the child as one subjected to other sexual abuse. Similar to these situations, the first sexual affront upon a child shown to be performing in obscene publications and indecent shows, or under circumstances falling under Section 6, is already a violation of Section 5(b) because these circumstances are sufficient to qualify the child as one subjected to other sexual abuse.

This is also the reason why the definition of "child abuse" adopted by the ponencia — based on Section 3,15 R.A. 7610 and Section 2(g) of the Rules and Regulations on the Reporting and Investigation of Child Abuse Cases — does not require the element of habituality to qualify an act as "child abuse" or "sexual abuse".16 However, this absence of habituality as an element of the crime punished by Section 5(b), R.A. 7610 does not mean that the law would apply in each and every case of sexual abuse. To the contrary, it only means that the first act of sexual abuse would be punishable by Section 5(b), R.A. 7610 if done under the circumstances of being "exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse." For example, if the child-victim was newly recruited by the prostitution den, even the first person who would have sexual intercourse with her under said conditions would be punished under Section 5(b), R.A. 7610.

Moreover, the deliberations of R.A. 7610 support the view that Section 5(b) is limited only to sexual abuses committed against children that are EPSOSA. I thus quote anew Senator Rasul, one of R.A. 7610's sponsors, who, in her sponsorship speech, stated:

Senator Rasul. x x x

x x x x

But undoubtedly, the most disturbing, to say the least, is the persistent report of children being sexually exploited and molested for purely material gains. Children with ages ranging from three to 18 years are used and abused. We hear and read stories of rape, manhandling and sexual molestation in the hands of cruel sexual perverts, local and foreigners alike. As of October 1990, records show that 50 cases of physical abuse were reported, with the ratio of six females to four males. x x x

x x x x

x x x No less than the Supreme Court, in the recent case of People vs. Ritter, held that we lack criminal laws which will adequately protect street children from exploitation by pedophiles. x x x17 (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

To recall, People v. Ritter18 is a 1991 case which involved an Austrian national who was charged with rape with homicide for having ultimately caused the death of Rosario, a street child, by inserting a foreign object into her vagina during the course of performing sexual acts with her. Ritter was acquitted based on reasonable doubt on account of, among others, the failure of the prosecution to (1) establish the age of Rosario to be within the range of statutory rape, and (2) show force or intimidation as an essential element of rape in the face of the finding that Rosario was a child prostitute who willingly engaged in sexual acts with Ritter. While the Court acquitted Ritter, it did make the observation that there was, at that time, a "lack of criminal laws which will adequately protect street children from exploitation by pedophiles, pimps, and, perhaps, their own parents or guardians who profit from the sale of young bodies."19

The enactment of R.A. 7610 was the response by the legislature to the observation of the Court that there was a gap in the law. Of relevance is the exchange between Senators Enrile and Lina, which I quote anew, that confirms that the protection of street children from exploitation is the foremost thrust of R.A. 7610:

Senator Enrile. Pareho silang hubad na hubad at naliligo. Walang ginagawa. Walang touching po, basta naliligo lamang. Walang akapan, walang touching, naliligo lamang sila. Ano po ang ibig sabihin noon? Hindi po ba puwedeng sabihin, kagaya ng standard na ginamit natin, na UNDER CIRCUMSTANCES WHICH WOULD LEAD A REASONABLE PERSON TO BELIEVE THAT THE CHILD IS ABOUT TO BE SEXUALLY EXPLOITED, OR ABUSED.

Senator Lina. Kung mayroon pong balangkas or amendment to cover that situation, tatanggapin ng Representation na ito. Baka ang sitwasyong iyon ay hindi na ma-cover nito sapagkat, at the back of our minds, Mr. President, ang sitwasyong talagang gusto nating ma-address ay maparusahan iyong tinatawag na "pedoph[i]lia" or prey on our children. Hindi sila makakasuhan sapagkat their activities are undertaken or are committed in the privacy of homes, inns, hotels, motels and similar establishments.20 (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

And when he explained his vote, Senator Lina stated the following:

With this legislation, child traffickers could be easily prosecuted and penalized. Incestuous abuse and those where victims are under twelve years of age are penalized gravely, ranging from reclusion temporal to reclusion perpetua, in its maximum period. It also imposes the penalty of reclusion temporal in its medium period to reclusion perpetua, equivalent to a 14-30 year prison term for those "(a) who promote or facilitate child prostitution; (b) commit the act of sexual intercourse or lascivious conduct with a child exploited in prostitution; (c) derive profit or advantage whether as manager or owner of an establishment where the prostitution takes place or of the sauna, disco, bar resort, place of entertainment or establishment serving as a cover or which engages in a prostitution in addition to the activity for which the license has been issued to said establishment.21 (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

The Senate deliberations on R.A. 7610 are replete with similar disquisitions that all show the intent to make the law applicable to cases involving child exploitation through prostitution, sexual abuse, child trafficking, pornography and other types of abuses. To repeat, the passage of the law was the Senate's act of heeding the call of the Court to afford protection to a special class of children and not to cover any and all crimes against children that are already covered by other penal laws, such as the RPC and Presidential Decree No. 603, otherwise known as the Child and Youth Welfare Code.

The Angara Amendment, which added the phrase "who for money, profit, or any other consideration or due to coercion or influence of any adult, syndicate or group, indulge in sexual intercourse or lascivious conduct" in Section 5(b), relied upon by the ponencia to support its argument that the law applies in each and every case where the victim of the sexual abuse is a child, 22 does not actually support its proposition. The deliberations on the said Angara Amendment are quoted in full below if only to understand the whole context of the amendment:

Senator Angara: I see. Then, I move to page 3, Mr. President, Section 4, if it is still in the original bill.

Senator Lina: Yes, Mr. President.

Senator Angara: I refer to line 9, "who for money or profit". I would like to amend this, Mr. President, to cover a situation where the minor may have been coerced or intimidated into this lascivious conduct, not necessarily for money or profit, so that we can cover those situations and not leave a loophole in this section.

The proposal I have is something like this: "WHO FOR MONEY, PROFIT, OR ANY OTHER CONSIDERATION OR DUE TO THE COERCION OR INFLUENCE OF ANY ADULT, SYNDICATE OR GROUP INDULGE, etcetera.

The President Pro Tempore. I see. That would mean also changing the subtitle of Section 4. Will it no longer be child prostitution?

Senator Angara. No, no. Not necessarily, Mr. President, because we are still talking of the child who is being misused for sexual purposes either for money or for consideration. What I am trying to cover is the other consideration. Because, here, it is limited only to the child being abused or misused for sexual purposes, only for money or profit.

I am contending, Mr. President, that there may be situations where the child may not have been used for profit or...

The President Pro Tempore. So, it is no longer prostitution. Because the essence of prostitution is profit.

Senator Angara. Well, the Gentleman is right. Maybe the heading ought to be expanded. But, still, the President will agree that that is a form or manner of child abuse.

The President Pro Tempore. What does the Sponsor say? Will the Gentleman kindly restate the amendment?

ANGARA AMENDMENT

Senator Angara. The new section will read something like this, Mr. President: MINORS, WHETHER MALE OR FEMALE, WHO FOR MONEY, PROFIT, OR ANY OTHER CONSIDERATION OR DUE TO THE COERCION OR INFLUENCE OF ANY ADULT, SYNDICATE OR GROUP INDULGE IN SEXUAL INTERCOURSE, etcetera.

Senator Lina. It is accepted, Mr. President.23 (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

Clear from the said deliberations is the intent to still limit the application of Section 5(b) to a situation where the child is used for sexual purposes for a consideration, although it need not be monetary. The Angara Amendment, even as it adds the phrase "due to the coercion or influence of any adult, syndicate or group", did not transform the provision into one that has universal application, like the provisions of the RPC. To repeat, Section 5(b) only applies in the specific and limited instances where the child-victim is EPSOSA.

The ponencia further argues that the interpretation of Section 5(b), R.A. 7610 in the cases of Dimakuta, Quimvel, and Caoili is more consistent with the objective of the law,24 and of the Constitution,25 to provide special protection to children from all forms of abuse, neglect, cruelty, exploitation and discrimination, and other conditions prejudicial to their development. It adds that:

The term "other sexual abuse," on the other hand, should be construed in relation to the definitions of "child abuse" under Section 3, Article I of R.A. No. 7610 and "sexual abuse" under Section 2(g) of the Rules and Regulations on the Reporting and Investigation of Child Abuse Cases. In the former provision, "child abuse" refers to the maltreatment, whether habitual or not, of the child which includes sexual abuse, among other matters. In the latter provision, "sexual abuse" includes the employment, use, persuasion, inducement, enticement or coercion of a child to engage in, or assist another person to engage in, sexual intercourse or lascivious conduct or the molestation, prostitution, or incest with children. x x x26 (Emphasis in the original)

With utmost respect to the distinguished ponente, these arguments unduly extend the letter of the Section 5(b) of R.A. 7610 for the sake of supposedly reaching its objectives. For sure, these arguments violate the well-established rule that penal statutes are to be strictly construed against the government and liberally in favor of the accused.27 In the interpretation of a penal statute, the tendency is to give it careful scrutiny, and to construe it with such strictness as to safeguard the rights of the defendant.28 As the Court in People v. Garcia29 reminds:

x x x "Criminal and penal statutes must be strictly construed, that is, they cannot be enlarged or extended by intendment, implication, or by any equitable considerations. In other words, the language cannot be enlarged beyond the ordinary meaning of its terms in order to carry into effect the general purpose for which the statute was enacted. Only those persons, offenses, and penalties, clearly included, beyond any reasonable doubt, will be considered within the statute's operation. They must come clearly within both the spirit and the letter of the statute, and where there is any reasonable doubt, it must be resolved in favor of the person accused of violating the statute; that is, all questions in doubt will be resolved in favor of those from whom the penalty is sought." x x x30 (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

What is more, the aforementioned objective of R.A. 7610 and the Constitution — that is, to afford special protection to children from all forms of abuse, neglect, cruelty and discrimination, and other conditions prejudicial to their development — is actually achieved, not by the unwarranted expansion of Section 5(b) in particular, but by the law itself read as a whole.

The statements of Senators Lina and Rasul,31 relied upon by the ponencia, to the effect that R.A. 7610 was passed in keeping with the Constitutional mandate that "[t]he State shall defend the right of children to assistance, including proper care and nutrition, and special protection from all forms of neglect, abuse, cruelty, exploitation, and other conditions prejudicial to their development" do not support the expanded interpretation of Section 5(b) at all. In fact, the Senators were lauding the enactment into law of R.A. 7610 because it provided a holistic approach in protecting children from various abuses and forms of neglect that were not punished by law before its enactment. To illustrate, the following are the novel areas for the protection of children that are covered through the enactment of R.A. 7610:

1. Protection of children from Child Prostitution and Other Sexual Abuse (Sections 5 and 6, Article III, R.A. 7610);

2. Protection of children against Child Trafficking (Sections 7 and 8, Article IV, R.A. 7610);

3. Protection of children from being used in Obscene Publications and Indecent Shows (Section 9, Article V, R.A. 7610);

4. Other forms of abuse, including the use of children for illegal activities (Section 10, Article VI, R.A. 7610);

5. Protection of children against Child Labor (Section 12, Article VIII, R.A. 7610);

6. Special protection for Children of Indigenous Cultural Communities (Sections 17-21, Article IX, R.A. 7610); and

7. Rights of Children in Situations of Armed Conflict (Sections 22- 26, Article X, R.A. 7610).

The ponencia further uses the extended explanation by Senator Lina of his vote on the bill that became R.A. 7610 to support its position. The ponencia argues:

In the extended explanation of his vote on Senate Bill No. 1209, Senator Lina emphasized that the bill complements the efforts the Senate has initiated towards the implementation of a national comprehensive program for the survival and development of Filipino children, in keeping with the Constitutional mandate that "[t]he State shall defend the right of children to assistance, including proper care and nutrition, and special protection from all forms of neglect, abuse, cruelty, exploitation, and other conditions prejudicial to their development. " Senator Lina also stressed that the bill supplies the inadequacies of the existing laws treating crimes committed against children, namely, the RPC and the Child and Youth Welfare Code, in the light of the present situation, i.e., current empirical data on child abuse indicate that a stronger deterrence is imperative.32

For full context, however, Senator Lina's explanation is quoted in its entirety below:

EXPLANATION OF VOTE OF SENATOR LINA

x x x x

The following is the written Explanation of Vote submitted by Senator Lina:

In voting for this measure, we keep in mind some thirty (30) million children who are below 18 years of age, of which about 25.3 million are children below fifteen years of age. Of these number, it is estimated that at least one percent (1%) are subject to abuse, exploitation, neglect, and of crimes related to trafficking.

These are the vulnerable and sensitive sectors of our society needing our care and protection so that they will grow to become mature adults who are useful members of the society and potential leaders of our Nation.

This bill which is a consolidation of Senate Bill No. 487, (one of the earlier bills I filed), and Senate Bill No. 727 authored by Senator Mercado with amendments introduced by Senators Rasul, Shahani, Tañada and the members of the Committee on Women and Family Relations, complements the efforts we have initiated towards the implementation of a national comprehensive program for the survival and development of Filipino children, in keeping with the Constitutional mandate that "The State shall defend the right of the children to assistance, including proper care and nutrition, and special protection from all forms of neglect, abuse, cruelty, exploitation, and other conditions prejudicial to their development" (Article XV, Section 3, par. 2), and also with the duty we assumed as signatory of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Republic Act No. 6972 (which was approved on November 23, 1990), The Barangay Level Total Development and Protection of Children Act provides the foundation for a network of barangay-level crises intervention and sanctuaries for endangered children up to six years of age who need to be rescued from an unbearable home situation, and RA 7160, The Local Government Code of 1991 (which was approved on November 26, 1991) mandates every barangay, as soon as feasible, to set up such center to serve children up to six years of age. These laws embody the institutional protective mechanisms while this present bill provides a mechanism for strong deterrence against the commission of abuse and exploitation.

This bill which I co-sponsored supplies the inadequacies of our existing laws treating crimes committed against children, namely, the Revised Penal Code and the Child and Youth Welfare Code, in the light of the present situation. Current empirical data on child abuse indicate that a stronger deterrent is imperative.

Child abuse is now clearly defined and more encompassing as to include "the act of unreasonably depriving a child of basic needs for survival, such as food and shelter or a combination of both or a case of an isolated event where the injury is of a degree that if not immediately remedied could seriously impair the child's growth and development or result in permanent incapacity or death."

With this legislation, child traffickers could be easily prosecuted and penalized. Incestuous abuse and those where victims are under twelve years of age are penalized gravely, ranging from reclusion temporal to reclusion perpetua, in its maximum period. It also imposes the penalty of reclusion temporal in its medium period to reclusion perpetua, equivalent to a 14-30 year prison term for those "(a) who promote or facilitate child prostitution; (b) commit the act of sexual intercourse or lascivious conduct with a child exploited in prostitution; (c) derive profit or advantage whether as manager or owner of an establishment where the prostitution takes place or of the sauna, disco, bar resort, place of entertainment or establishment serving as a cover or which engages in a prostitution in addition to the activity for which the license has been issued to said establishment.["]

Attempt to commit child prostitution and child trafficking, including the act of inducing or coercing a child to perform in obscene publications or indecent shows whether live or in video, are also penalized. And additional penalties are imposed if the offender is a foreigner, a government official or employee.

For the foregoing reasons, I vote Yes, and I believe that as an elected legislator, this is one of the best legacies that I can leave to our children and youth.33 (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

If read in its entirety – instead of placing emphasis on certain paragraphs – the vote of Senator Lina, therefore, supports the argument that the law applies only to specific and limited instances. Senator Lina even discussed Section 5(b) in particular in the above extended explanation, still within the context of prostitution.

Thus, to emphasize, R.A. 7610 was being lauded for being the response to the Constitutional mandate for the State to provide special protection to children from all forms of neglect, abuse, cruelty or exploitation because it provides for protection of children in special areas where there were gaps in the law prior to its enactment. This is the reason why, as the ponencia itself recognizes, "the enactment of R.A. No. 7610 was a response of the legislature to the observation of the Court [in People v. Ritter] that there was a gap in the law because of the lack of criminal laws which adequately protect street children from exploitation of pedophiles."34

That R.A. 7610 was the legislature's attempt in providing a comprehensive law to adequately protect children from all forms of abuse, neglect, cruelty or exploitation, is best expressed in the law's Section 10(a) (not Section 5(b)), which provides:

SEC. 10. Other Acts of Neglect, Abuse, Cruelty or Exploitation and Other Conditions Prejudicial to the Child's Development. —

(a) Any person who shall commit any other acts of child abuse, cruelty or exploitation or be responsible for other conditions prejudicial to the child's development including those covered by Article 59 of Presidential Decree No. 603, as amended, but not covered by the Revised Penal Code, as amended, shall suffer the penalty of prision mayor in its minimum period. (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

To stress, R.A. 7610 as a whole tried to cover as many areas where children experience abuse, neglect, cruelty, or exploitation, and where it fails to explicitly provide for one, the catch-all provision in Section 10(a) was crafted to cover it. Again, these — the other provisions of R.A. 7610, complemented by its catch-all provision in Section 10(a) — are the reasons why R.A. 7610 was being lauded for providing protection to children from all forms of abuse, neglect, cruelty, or exploitation. It is definitely not the expanded interpretation of Section 5(b) created by Dimakuta, Quimvel, and Caoili, as reiterated in the ponencia.

Other reasons put forth by the ponencia

In further rebutting the point I and Justice Perlas-Bernabe raised — that a person could be convicted of violation of Article 336 in relation to Section 5(b) only upon allegation and proof of the unique circumstance of being EPSOSA — the ponencia reasons that "the provisos of Section 5(b) itself explicitly state that it must also be read in light of the provisions of the RPC, thus: 'Provided, That when the victim is under twelve (12) years of age, the perpetrators shall be prosecuted under Article 335, paragraph 3, for rape and Article 336 of Act No. 3815, as amended, the Revised Penal Code, for rape or lascivious conduct, as the case may be[:] Provided, That the penalty for lascivious conduct when the victim is under twelve (12) years of age shall be reclusion temporal in its medium period."'35

With due respect, I fail to see how the above provisos supposedly negate the points Justice Perlas-Bernabe and I raised. The provisos only provide that the perpetrators shall be prosecuted under the RPC when the victim is below 12 years old, and then impose the corresponding penalty therefor. The provisos provide for nothing more. To illustrate clearly, the provisos only provide for the following:

General rule: when the child-victim is "exploited in prostitution and other sexual abuse" or EPSOSA, then the perpetrator should be prosecuted under Section 5(b), R.A. 7610. Penalty: reclusion temporal medium period to reclusion perpetua.

a. Effect of first proviso only: if (1) the act constitutes Rape by sexual intercourse and (2) the child-victim, still EPSOSA, is below 12 years old, then the perpetrator should be prosecuted under the Rape provision of the RPC. Penalty: reclusion perpetua.

b. Effect of the first and second provisos, combined: if (1) the act constitutes Lascivious Conduct36 and (2) the child-victim, still EPSOSA, is below 12 years old, then the perpetrator should be prosecuted under the Acts of Lasciviousness or Rape by Sexual Assault provisions of the RPC. Penalty: reclusion temporal in its medium period.

Verily, it is hard to see how the provisos supposedly negate the assertion that Section 5(b) only applies when the child victim is EPSOSA.

At this juncture, I would like to digress and thresh out a point of divergence between my view and Justice Perlas-Bernabe's. According to her, the afore-quoted provisos are "a textual indicator that RA 7610 has a specific application only to children who are pre-disposed to 'consent' to a sexual act because they are 'exploited in prostitution or subject to other sexual abuse."'37 She further explains her view:

While the phrase "shall be prosecuted under" has not been discussed in existing case law, it is my view that the same is a clear instruction by the lawmakers to defer any application of Section 5 (b), Article III of RA 7610, irrespective of the presence of EPSOSA, when the victim is under twelve (12). As a consequence, when an accused is prosecuted under the provisions of the RPC, only the elements of the crimes defined thereunder must be alleged and proved. Necessarily too, unless further qualified, as in the second proviso, i.e., Provided, That the penalty for lascivious conduct when the victim is under twelve (12) years of age shall be reclusion temporal in its medium period, the penalties provided under the RPC would apply.38 (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

On her proposed table of penalties, Justice Perlas-Bernabe reiterates her point that the element of being EPSOSA becomes irrelevant when the victim is below 12 years old because of the operation of the provisos under Section 5(b) of R.A. 7610.

I partially disagree.

I concur with Justice Perlas-Bernabe's view only to the extent that when Section 5(b), R.A. 7610 defers to the provisions of the RPC when the victim is below 12 years old, then this means that "only the elements of the crimes defined thereunder must be alleged and proved."39 However, I would have to express my disagreement to the sweeping statement that when the victim is below 12 years old, that the element of being EPSOSA becomes irrelevant.

Again, at the risk of being repetitive, Section 5(b) of R.A. 7610 is a penal provision which has a special and limited application that requires the element of being EPSOSA for it to apply. Differently stated, it is the element of being EPSOSA that precisely triggers the application of Section 5(b) of R.A. 7610. Hence, the provisos — both the one referring the prosecution of the case back to the RPC, and the other which increases the penalties for lascivious conduct — would apply only when the victim is both below 12 years old and EPSOSA.

The blanket claim that being EPSOSA is irrelevant when the victim is below 12 years old leads to the exact same evils that this opinion is trying to address, i.e., the across-the-board application of Section 5(b) of R.A. 7610 in each and every case of sexual abuse committed against children, although limited only to the instance that the victim is below 12 years old.

This indiscriminate application of the provisos in Section 5(b) of R.A. 7610 does not seem to matter when the act committed by the accused constitutes rape by sexual intercourse. To illustrate, the direct application of the RPC or its application through the first proviso of Section 5(b) would lead to the exact same result: a punishment or penalty of reclusion perpetua on the accused upon conviction.

The same is not true, however, when the act constitutes only lascivious conduct. I refer to the tables below for ease of reference:

| Act committed constitutes Acts of Lasciviousness |

Penalty |

| a. Victim is below 12, not EPSOSA (thus, Article 336 of the RPC is directly applied) |

Prision correccional |

| b. Victim is below 12, but EPSOSA (thus, the provisos of Section 5(b) apply) |

Reclusion temporal in its medium period |

| Act committed constitutes Rape by Sexual Assault |

Penalty |

| a. Victim is below 12, not EPSOSA (thus, Article 226-A(2) of the RPC, as amended by R.A. 8353 is directly applied) |

Prision mayor |

| b. Victim is below 12, but EPSOSA (thus, the provisos of Section 5(b) applies) |

Reclusion temporal in its medium period |

Thus, as shown by the foregoing table, the element of being EPSOSA is relevant when the victim is below 12 years old as the penalties will be increased to those provided for by R.A. 7610.

The ponencia further points out that "[i]t is hard to understand why the legislature would enact a penal law on child abuse that would create an unreasonable classification between those who are considered as x x x EPSOSA and those who are not."40

On the contrary, the reasons of the legislature are not that hard to understand.

The classification between the children considered as EPSOSA and those who are not is a reasonable one. Children who are EPSOSA may be considered a class of their own, whose victimizers deserve a specific punishment. For instance, the legislature, in enacting R.A. 9262 or the Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act, created a distinction between (1) women who were victimized by persons with whom they have or had a sexual or dating relationship and (2) all other women-victims of abuse. This distinction is valid, and no one argues that R.A. 9262 applies or should apply in each and every case where the victim of abuse is a woman.

The ponencia then insists that a perpetrator of acts of lasciviousness against a child that is not EPSOSA cannot be punished by merely prision correccional for to do so would be "contrary to the letter and intent of R.A. 7610 to provide for stronger deterrence and special protection against child abuse, exploitation and discrimination."41 The ponencia makes the foregoing extrapolation from the second to the last paragraph of Section 10 of R.A. 7610, which provides:

For purposes of this Act, the penalty for the commission of acts punishable under Articles 248, 249, 262, paragraph 2, and 263, paragraph 1 of Act No. 3815, as amended, the Revised Penal Code, for the crimes of murder, homicide, other intentional mutilation, and serious physical injuries, respectively, shall be reclusion perpetua when the victim is under twelve (12) years of age. The penalty for the commission of acts punishable under Articles 337, 339, 340 and 341 of Act No. 3815, as amended, the Revised Penal Code, for the crimes of qualified seduction, acts of lasciviousness with the consent of the offended party, corruption of minors, and white slave trade, respectively, shall be one (1) degree higher than that imposed by law when the victim is under twelve (12) years of age. (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

Again, I submit that a logical leap is committed: since R.A. 7610 increased the penalties under Articles 337, 339, 340 and 341 of the RPC, the ponencia posits that this likewise affected Article 336 of the RPC or the provisions on acts of lasciviousness. However, as the deliberations of R.A. 7610, quoted42 by the ponencia itself, show:

Senator Lina. x x x

For the information and guidance of our Colleagues, the phrase "child abuse" here is more descriptive than a definition that specifies the particulars of the acts of child abuse. As can be gleaned from the bill, Mr. President, there is a reference in Section 10 to the "Other Acts of Neglect, Abuse, Cruelty or Exploitation and Other Conditions Prejudicial to the Child's Development."

We refer, for example, to the Revised Penal Code. There are already acts described and punishable under the Revised Penal Code and the Child and Youth Welfare Code. These are all enumerated already, Mr. President. There are particular acts that are already being punished.

But we are providing a stronger deterrence against child abuse and exploitation by increasing the penalties when the victim is a child. That is number one. We define a child as "one who is 15 years and below.

The President Pro Tempore. Would the Sponsor then say that this bill repeals, by implication or as a consequence, the law he just cited for the protection of the child as contained in that Code just mentioned, since this provides for stronger deterrence against child abuse and we have now a Code for the protection of the child? Would that Code be now amended by this Act, if passed?

Senator Lina. We specified in the bill, Mr. President, increase in penalties. That is one. But, of course, that is not everything included in the bill. There are other aspects like making it easier to prosecute these cases of pedophilia in our country. That is another aspect of the bill.

The other aspects of the bill include the increase in the penalties on acts committed against children; and by definition, children are those below 15 years of age.

So, it is an amendment to the Child and Youth Welfare Code, Mr. President. This is not an amendment by implication. We made direct reference to the Articles in the Revised Penal Code and in the Articles in the Child and Youth Welfare Code that are amended because of the increase in penalties. (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

Given the clear import of the above — that the legislature expressly named the provisions it sought to amend through R.A. 7610 — the ponencia cannot now insist on an amendment by implication. The position that Section 5(b), R.A. 7610 rendered Article 336 of the RPC inoperative when the victim is a child, despite the lack of a manifest intention to the effect as expressed in the letter of the said provision, is unavailing. Differently stated, an implied partial repeal cannot be insisted upon in the face of the express letter of the law. I therefore believe that any continued assertion that Section 5(b) of R.A. 7610 applies to any and all cases of acts of lasciviousness committed against children, whether under the context of being EPSOSA or not, is not in accordance with the law itself.

When Section 5(b), R.A. 7610 applies

As demonstrated above, both literal and purposive tests, therefore, show that there is nothing in the language of the law or in the Senate deliberations that supports the conclusion that Section 5(b), R.A. 7610 subsumes all instances of sexual abuse against children.

Thus, for a person to be convicted of violating Section 5(b), R.A. 7610, the following essential elements need to be proved: (1) the accused commits the act of sexual intercourse or lascivious conduct; (2) the said act is performed with a child "exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse"; and (3) the child whether male or female, is below 18 years of age.43

The unique circumstances of the children "exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse" — for which the provisions of R.A. 7610 are intended — are highlighted in this exchange:

The Presiding Officer [Senator Mercado]. Senator Pimentel.

Senator Pimentel. Just this question, Mr. President, if the Gentleman will allow.

Will this amendment also affect the Revised Penal Code provisions on seduction?

Senator Lina. No, Mr. President. Article 336 of Act No. 3815 will remain unaffected by this amendment we are introducing here. As a backgrounder, the difficulty in the prosecution of so-called "pedophiles" can be traced to this problem of having to catch the malefactor committing the sexual act on the victim. And those in the law enforcement agencies and in the prosecution service of the Government have found it difficult to prosecute. Because if an old person, especially a foreigner, is seen with a child with whom he has no relation - blood or otherwise -- and they are just seen in a room and there is no way to enter the room and to see them in flagrante delicto, then it will be very difficult for the prosecution to charge or to hale to court these pedophiles.

So, we are introducing into this bill, Mr. President, an act that is considered already an attempt to commit child prostitution. This, in no way, affects the Revised Penal Code provision on acts of lasciviousness or qualified seduction.44 (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

Bearing these in mind, there is no disagreement as to the first and third elements of Section 5(b). The core of the discussion relates to the meaning of the second element — that the act of sexual intercourse or lascivious conduct is performed with a "child exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse."

To my mind, a person can only be convicted of violation of Article 336 in relation to Section 5(b), upon allegation and proof of the unique circumstances of the child — that he or she is "exploited in prostitution or subject to other sexual abuse." In this light, I quote in agreement Justice Carpio's dissenting opinion in Olivarez v. Court of Appeals:45

Section 5 of RA 7610 deals with a situation where the acts of lasciviousness are committed on a child already either exploited in prostitution or subjected to "other sexual abuse." Clearly, the acts of lasciviousness committed on the child are separate and distinct from the other circumstance — that the child is either exploited in prostitution or subjected to "other sexual abuse."

x x x x

Section 5 of RA 7610 penalizes those "who commit the act of sexual intercourse or lascivious conduct with a child exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse." The act of sexual intercourse or lascivious conduct may be committed on a child already exploited in prostitution, whether the child engages in prostitution for profit or someone coerces her into prostitution against her will. The element of profit or coercion refers to the practice of prostitution, not to the sexual intercourse or lascivious conduct committed by the accused. A person may commit acts of lasciviousness even on a prostitute, as when a person mashes the private parts of a prostitute against her will.

The sexual intercourse or act of lasciviousness may be committed on a child already subjected to other sexual abuse. The child may be subjected to such other sexual abuse for profit or through coercion, as when the child is employed or coerced into pornography. A complete stranger, through force or intimidation, may commit acts of lasciviousness on such child in violation of Section 5 of RA 7610.

The phrase "other sexual abuse" plainly means that the child is already subjected to sexual abuse other than the crime for which the accused is charged under Section 5 of RA 7610. The "other sexual abuse" is an element separate and distinct from the acts of lasciviousness that the accused performs on the child. The majority opinion admits this when it enumerates the second element of the crime under Section 5 of RA 7610 — that the lascivious "act is performed with a child x x x subjected to other sexual abuse."46 (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

Otherwise stated, in order to impose the higher penalty provided in Section 5(b) as compared to Article 336, it must be alleged and proved that the child — (1) for money, profit, or any other consideration or (2) due to the coercion or influence of any adult, syndicate or group — indulges in sexual intercourse or lascivious conduct.

In People v. Abello47 (Abello), one of the reasons the accused was convicted of rape by sexual assault and acts of lasciviousness, as penalized under the RPC and not under Section 5(b), was because there was no showing of coercion or influence required by the second element. The Court ratiocinated:

In Olivarez v. Court of Appeals, we explained that the phrase, "other sexual abuse" in the above provision covers not only a child who is abused for profit, but also one who engages in lascivious conduct through the coercion or intimidation by an adult. In the latter case, there must be some form of compulsion equivalent to intimidation which subdues the free exercise of the offended party's will.

In the present case, the prosecution failed to present any evidence showing that force or coercion attended Abello's sexual abuse on AAA; the evidence reveals that she was asleep at the time these crimes happened and only awoke when she felt her breasts being fondled. Hence, she could have not resisted Abello's advances as she was unconscious at the time it happened. In the same manner, there was also no evidence showing that Abello compelled her, or cowed her into silence to bear his sexual assault, after being roused from sleep. Neither is there evidence that she had the time to manifest conscious lack of consent or resistance to Abello's assault.48 (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

The point of the foregoing is simply this: Articles 266-A and 336 of the RPC remain as operative provisions, and the crime of rape and acts of lasciviousness continue to be crimes separate and distinct from a violation under Section 5(b), R.A. 7610.

The legislative intent to have the provisions of R.A. 7610 to operate side by side with the provisions of the RPC — and a recognition that the latter remain effective — can be gleaned from Section 10 of the law, which again I quote:

SEC. 10. Other Acts of Neglect, Abuse, Cruelty or Exploitation and Other Conditions Prejudicial to the Child's Development. —

(a) Any person who shall commit any other acts of child abuse, cruelty or exploitation or be responsible for other conditions prejudicial to the child's development including those covered by Article 59 of Presidential Decree No. 603, as amended, but not covered by the Revised Penal Code, as amended, shall suffer the penalty of prision mayor in its minimum period. (Emphasis and underscoring)

This is confirmed by Senator Lina in his sponsorship speech of R.A. 7610, thus:

Senator Lina. x x x

x x x x

Senate Bill No. 1209, Mr. President, is intended to provide stiffer penalties for abuse of children and to facilitate prosecution of perpetrators of abuse. It is intended to complement provisions of the Revised Penal Code where the crimes committed are those which lead children to prostitution and sexual abuse, trafficking in children and use of the young in pornographic activities.

These are the three areas of concern which are specifically included in the United Nations Convention o[n] the Rights of the Child. As a signatory to this Convention, to which the Senate concurred in 1990, our country is required to pass measures which protect the child against these forms of abuse.

x x x x

Mr. President, this bill on providing higher penalties for abusers and exploiters, setting up legal presumptions to facilitate prosecution of perpetrators of abuse, and complementing the existing penal provisions of crimes which involve children below 18 years of age is a part of a national program for protection of children.

x x x x

Mr. President, subject to perfecting amendments, I am hopeful that the Senate will approve this bill and thereby add to the growing program for special protection of children and youth. We need this measure to deter abuse. We need a law to prevent exploitation. We need a framework for the effective and swift administration of justice for the violation of the rights of children.49 (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

It is thus erroneous to rule that R.A. 7610 applies in each and every case where the victim is a minor although he or she was not proved, much less alleged, to be a child "exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse." I invite the members of the Court to go back to the mindset and ruling adopted in Abello where it was held that "since R.A. No. 7610 is a special law referring to a particular class in society, the prosecution must show that the victim truly belongs to this particular class to warrant the application of the statute's provisions. Any doubt in this regard we must resolve in favor of the accused."50

There is no question that, in a desire to bring justice to child victims of sexual abuse, the Court has, in continually applying the principles laid down in Dimakuta, Quimvel, and Caoili, sought the application of a law that imposes a harsher penalty on its violators. However, as noble as this intent is, it is fundamentally unsound to let the penalty determine the crime. To borrow a phrase, this situation is letting the tail wag the dog.

To be sure, it is the acts committed by the accused, and the crime as defined by the legislature — not the concomitant penalty — which determines the applicable law in a particular set of facts. As the former Second Division of the Court in People v. Ejercito,51 a case penned by Justice Perlas-Bernabe and concurred in by the ponente, correctly held:

Neither should the conflict between the application of Section 5(b) of RA 7610 and RA 8353 be resolved based on which law provides a higher penalty against the accused. The superseding scope of RA 8353 should be the sole reason of its prevalence over Section 5(b) of RA 7610. The higher penalty provided under RA 8353 should not be the moving consideration, given that penalties are merely accessory to the act being punished by a particular law. The term "'[p]enalty' is defined as '[p]unishment imposed on a wrongdoer usually in the form of imprisonment or fine'; '[p]unishment imposed by lawful authority upon a person who commits a deliberate or negligent act.'" Given its accessory nature, once the proper application of a penal law is determined over another, then the imposition of the penalty attached to that act punished in the prevailing penal law only follows as a matter of course. In the final analysis, it is the determination of the act being punished together with its attending circumstances - and not the gravity of the penalty ancillary to that punished act - which is the key consideration in resolving the conflicting applications of two penal laws.

x x x x

x x x Likewise, it is apt to clarify that if there appears to be any rational dissonance or perceived unfairness in the imposable penalties between two applicable laws (say for instance, that a person who commits rape by sexual assault under Article 266-A in relation to Article 266-B of the RPC, as amended by RA 8353 is punished less than a person who commits lascivious conduct against a minor under Section 5 (b) of RA 7610), then the solution is through remedial legislation and not through judicial interpretation. It is well-settled that the determination of penalties is a policy matter that belongs to the legislative branch of government. Thus, however compelling the dictates of reason might be, our constitutional order proscribes the Judiciary from adjusting the gradations of the penalties which are fixed by Congress through its legislative function. As Associate Justice Diosdado M. Peralta had instructively observed in his opinion in Cao[i]li:

Curiously, despite the clear intent of R.A. 7610 to provide for stronger deterrence and special protection against child abuse, the penalty [reclusion temporal] medium] when the victim is under 12 years old is lower compared to the penalty [reclusion temporal medium to reclusion perpetua] when the victim is 12 years old and below 18. The same holds true if the crime of acts of lasciviousness is attended by an aggravating circumstance or committed by persons under Section 31, Article XII of R.A. 7610, in which case, the imposable penalty is reclusion perpetua. In contrast, when no mitigating or aggravating circumstance attended the crime of acts of lasciviousness, the penalty therefor when committed against a child under 12 years old is aptly higher than the penalty when the child is 12 years old and below 18. This is because, applying the Indeterminate Sentence Law, the minimum term in the case of the younger victims shall be taken from reclusion temporal minimum, whereas as [sic] the minimum term in the case of the older victims shall be taken from prision mayor medium to reclusion temporal minimum. It is a basic rule in statutory construction that what courts may correct to reflect the real and apparent intention of the legislature are only those which are clearly clerical errors or obvious mistakes, omissions, and misprints, but not those due to oversight, as shown by a review of extraneous circumstances, where the law is clear, and to correct it would be to change the meaning of the law. To my mind, a corrective legislation is the proper remedy to address the noted incongruent penalties for acts of lasciviousness committed against a child.52 (Additional emphasis and underscoring supplied)

Therefore, while I identify with the Court in its desire to impose a heavier penalty for sex offenders who victimize children — the said crimes being undoubtedly detestable — the Court cannot arrogate unto itself a power it does not have. Again, the Court's continuous application of R.A. 7610 in all cases of sexual abuse committed against minors is, with due respect, an exercise of judicial legislation which it simply cannot do.

At this point, it is important to point out that, as a result of this recurrent practice of relating the crime committed to R.A. 7610 in order to increase the penalty, the accused's constitutionally protected right to due process of law is being violated.

An essential component of the right to due process in criminal proceedings is the right of the accused to be sufficiently informed of the cause of the accusation against him. This is implemented through Rule 110, Section 9 of the Rules of Court, which states:

SEC. 9. Cause of the accusation. — The acts or omissions complained of as constituting the offense and the qualifying and aggravating circumstances must be stated in ordinary and concise language and not necessarily in the language used in the statute but in terms sufficient to enable a person of common understanding to know what offense is being charged as well as its qualifying and aggravating circumstances and for the court to pronounce judgment.

It is fundamental that every element of which the offense is composed must be alleged in the Information. No Information for a crime will be sufficient if it does not accurately and clearly allege the elements of the crime charged.53 The law essentially requires this to enable the accused suitably to prepare his defense, as he is presumed to have no independent knowledge of the facts that constitute the offense.54 From this legal backdrop, it may then be said that convicting an accused and relating the offenses to R.A. 7610 to increase the penalty when the Information does not state that the victim was a child "engaged in prostitution or subjected to sexual abuse" constitutes a violation of an accused's right to due process.

The ponencia counters that "[c]ontrary to the view of Justice Caguioa, there is likewise no such thing as a recurrent practice of relating the crime committed to R.A. No. 7610 in order to increase the penalty, which violates the accused's constitutionally protected right to due process of law."55

Yet, no matter the attempts to deny the existence of such practice, the inconsistencies in the ponencia itself demonstrate that its conclusions are driven by the desire to apply whichever law imposes the heavier penalty in a particular scenario. For instance, when discussing the applicable law when the act done by the accused constitutes "sexual intercourse", the ponencia has this discussion on the difference between the elements of "force or intimidation" in Rape under the RPC, on one hand, and "coercion or influence" under Section 5(b) of R.A. 7610, on the other:

In Quimvel, it was held that the term "coercion or influence" is broad enough to cover or even synonymous with the term "force or intimidation." Nonetheless, it should be emphasized that "coercion or influence" is used in Section 5 of R.A. No. 7610 to qualify or refer to the means through which "any adult, syndicate or group" compels a child to indulge in sexual intercourse. On the other hand, the use of "money, profit or any other consideration" is the other mode by which a child indulges in sexual intercourse, without the participation of "any adult, syndicate or group." In other words, "coercion or influence" of a child to indulge in sexual intercourse is clearly exerted NOT by the offender whose liability is based on Section 5(b) of R.A. No. 7610 for committing sexual act with a child exploited in prostitution or other sexual abuse. Rather, the "coercion or influence" is exerted upon the child by "any adult, syndicate, or group" whose liability is found under Section 5(a) for engaging in, promoting, facilitating, or inducing child prostitution, whereby sexual intercourse is the necessary consequence of the prostitution.

x x x x

As can be gleaned above, "force, threat or intimidation" is the element of rape under the RPC, while "due to coercion or influence of any adult, syndicate or group" is the operative phrase for a child to be deemed "exploited in prostitution or other sexual abuse," which is the element of sexual abuse under Section 5(b) of R.A. No. 7610. The "coercion or influence" is not the reason why the child submitted herself to sexual intercourse, but it was utilized in order for the child to become a prostitute. x x x

x x x x

Therefore, there could be no instance that an Information may charge the same accused with the crime of rape where "force, threat or intimidation" is the element of the crime under the RPC, and at the same time violation of Section 5(b) of R.A. No. 7610 where the victim indulged in sexual intercourse because she is exploited in prostitution either "for money, profit or any other consideration or due to coercion or influence of any adult, syndicate or group" - the phrase which qualifies a child to be deemed "exploited in prostitution or other sexual abuse" as an element of violation of Section 5(b) of R.A. No. 7610.56 (Emphasis and underscoring supplied; emphasis in the original omitted)

The ponencia, however, refuses to apply the above analysis when the act constitutes "sexual assault" or "lascivious conduct." It merely reiterates the Dimakuta ruling, and again anchors its conclusion on the policy of the State to provide special protection to children. The ponencia explains:

Third, if the charge against the accused where the victim is 12 years old or below is sexual assault under paragraph 2, Article 266-A of the RPC, then it may happen that the elements thereof are the same as that of lascivious conduct under Section 5(b) of R.A. No. 7610, because the term "lascivious conduct" includes introduction of any object into the genitalia, anus or mouth of any person. In this regard, We held in Dimakuta that in instances where a lascivious conduct" committed against a child is covered by R.A. No. 7610 and the act is likewise covered by sexual assault under paragraph 2, Article 266-A of the RPC [punishable by prision mayor], the offender should be held liable for violation of Section 5(b) of R.A. No. 7610 [punishable by reclusion temporal medium], consistent with the declared policy of the State to provide special protection to children from all forms of abuse, neglect, cruelty, exploitation and discrimination, and other conditions prejudicial to their development. x x x57

In another part of the ponencia, it partly concedes yet insists on its point, again by invoking the legislative intent behind the law. Thus:

Justice Caguioa is partly correct. Section 5(b) of R.A. No. 7610 is separate and distinct from common and ordinary acts of lasciviousness under Article 336 of the RPC. However, when the victim of such acts of lasciviousness is a child, as defined by law, We hold that the penalty is that provided for under Section 5(b) of R.A. No. 7610 – i.e., reclusion temporal medium in case the victim is under 12 years old, and reclusion temporal medium to reclusion perpetua when the victim is between 12 years old or under 18 years old or above 18 under special circumstances – and not merely prison (sic) correccional under Article 336 of the RPC. Our view is consistent with the legislative intent to provide stronger deterrence against all forms of child abuse, and the evil sought to be avoided by the enactment of R.A. No. 7610, which was exhaustively discussed during the committee deliberations of the House of Representatives[.]58

Clear from the foregoing is that the ponencia is willing to apply the inherent differences between the provisions of the RPC and R.A. 7610 when it comes to rape by sexual intercourse, and it is because the RPC imposes the heavier penalty of reclusion perpetua compared with the reclusion temporal medium to reclusion perpetua of Section 5(b), R.A. 7610. It is unwilling, however, to extend the same understanding of the differences between the provisions of the RPC and R.A. 7610 — and in the process contradicts itself — when the act constitutes "sexual assault", "acts of lasciviousness" or "lascivious conduct" for the reason that the RPC punishes the said acts with only prision correccional59 or prision mayor.60

Another instance in the ponencia that reveals that the penalty imposed is the primordial consideration in the choice of applicable law is the discussion on whether R.A. 8353 has superseded R.A. 7610. In the earlier part of the ponencia, it says:

Records of committee and plenary deliberations of the House of Representative (sic) and of the deliberations of the Senate, as well as the records of bicameral conference committee meetings, further reveal no legislative intent for R.A. No. 8353 to supersede Section 5(b) of R.A. No. 7610. x x x While R.A. No. 8353 contains a generic repealing and amendatory clause, the records of the deliberation of the legislature are silent with respect to sexual intercourse or lascivious conduct against children under R.A. No. 7610, particularly those who are 12 years old or below 18, or above 18 but are unable to fully take care or protect themselves from abuse, neglect, cruelty, exploitation or discrimination because of a physical or mental disability or condition.61 (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

Despite the clear pronouncement of the ponencia quoted above that R.A. 8353 did not supersede R.A. 7610, it would later on say:

x x x Indeed, while R.A. No. 7610 is a special law specifically enacted to provide special protection to children from all forms of abuse, neglect, cruelty, exploitation and discrimination and other conditions prejudicial to their development, We hold that it is contrary to the legislative intent of the same law if the lesser penalty (reclusion temporal medium to reclusion perpetua) under Section 5(b) thereof would be imposed against the perpetrator of sexual intercourse with a child 12 years of age or below 18.

Article 266-A, paragraph 1(a) in relation to Article 266-B of the RPC, as amended by R.A. No. 8353, is not only the more recent law, but also deals more particularly with all rape cases, hence, its short title "The Anti-Rape Law of 1997." R.A. No. 8353 upholds the policies and principles of R.A. No. 7610, and provides a "stronger deterrence and special protection against child abuse," as it imposes a more severe penalty of reclusion perpetua under Article 266-B of the RPC, or even the death penalty if the victim is (1) under 18 years of age and the offender is a parent, ascendant, step-parent, guardian, relative by consanguinity or affinity within the third civil degree, or common-law spouses of the parent of the victim; or (2) when the victim is a child below 7 years old.

It is basic in statutory construction that in case of irreconcilable conflict between two laws, the later enactment must prevail, being the more recent expression of legislative will. Indeed, statutes must be so construed and harmonized with other statutes as to form a uniform system of jurisprudence, and if several laws cannot be harmonized, the earlier statute must yield to the later enactment, because the later law is the latest expression of the legislative will. Hence, Article 266-B of the RPC must prevail over Section 5(b) of R.A. No. 7610.62 (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

It is again plainly evident from the above that the conclusion is heavily influenced by the corresponding penalties contained in the respective laws.

It is apparent, therefore, that the ponencia's choice of applicable law is primarily driven by the penalty imposed, all in the name of the State's policy to provide special protection to children. However, this would be in clear disregard of the right of the accused to be punished only to the extent that the law imposes a specific punishment on him.

This practice, without doubt, violates the rights of the accused in these cases. In Dimakuta, for example, one of the three oft-cited cases of the ponencia in reaching its conclusions, the crime was related to R.A. 7610 to increase the penalty even if the Information in the said case did not even mention the said law nor was there any allegation that the victim was EPSOSA. The Information in Dimakuta states:

That on or about the 24th day of September 2005, in the City of Las Piñas, Philippines, and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the above-named accused, with lewd designs, did then and there willfully, unlawfully and feloniously commit a lascivious conduct upon the person of one AAA, who was then a sixteen (16) year old minor, by then and there embracing her, touching her breast and private part against her will and without her consent and the act complained of is prejudicial to the physical and psychological development of the complainant.63

The Information filed in this case likewise did not specify that the victim was "exploited in prostitution or subjected to other sexual abuse," and in fact indicated "force and intimidation" as the mode of committing the crime — which, by the own ponencia's arguments above, triggers the application of the RPC, not Section 5(b) of R.A. 7610. The Information reads:

That sometime in the month of September 2011, at x x x, and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the above-named accused, by means of force, intimidation and with abuse of superior strength forcibly laid complainant AAA, a 9-year old minor in a cemented pavement, and did then and there willfully, unlawfully and feloniously inserted his finger into the vagina of the said AAA, against her will and consent.64 (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)