Manila

THIRD DIVISION

[ G.R. Nos. 177974, 206121, 219072 and 228802. August 17, 2022 ]

CYMAR INTERNATIONAL, INC., PETITIONER, VS. FARLING INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD., RESPONDENT.

D E C I S I O N

GAERLAN, J.:

Before the Court are four consolidated petitions for review, which all arose from a series of trademark disputes between petitioner Cymar International, Inc. (Cymar), a Philippine corporation engaged in the manufacture, marketing, sale, and promotion of baby products,1 and respondent Farling Industrial Company, Ltd. (Farling), a Republic of China (Taiwan)2 corporation engaged in the manufacture, sale, and distribution of various plastic, resinous, and baby products.3

Antecedents

1994 Cancellation Case (G.R. No. 177974)

On June 20, 1994, Farling filed five petitions4 before the then-Bureau of Patents, Trademarks and Technology Transfer, seeking the cancellation of the following trademark certificates of registration issued to Cymar:

1. Trademark Certificate of Registration No. 48144 issued on May 4, 1990 covering the trademark  , for baby products such as feeding bottles, nipples (rubber and silicon), funnel, nasal aspirator, breast reliever, ice bag and training bottles;5

, for baby products such as feeding bottles, nipples (rubber and silicon), funnel, nasal aspirator, breast reliever, ice bag and training bottles;5

2. Trademark Certificate of Registration No. 50483 issued on May 13, 1991 covering the trademark  , for diaper clips;

, for diaper clips;

3. Trademark Certificate of Registration No. 54569 issued on March 16, 1993 covering the trademark  , for t-shirts, sando, tie-side and other baby clothes;

, for t-shirts, sando, tie-side and other baby clothes;

4. Trademark Certificate of Registration No. 8348 issued on August 3, 1990 covering the trademark FARLIN LABEL, for diaper clip, with colors pink and blue;6

5. Trademark Certificate of Registration No. 8328 issued on July 18, 1990 covering the trademark FARLIN LABEL, for cotton buds, with colors blue, green, pink, yellow and gray.7

In the five petitions, Farling alleged that: 1) the  trademark is a coined word based on its corporate name;8 2) it is the rightful owner of the

trademark is a coined word based on its corporate name;8 2) it is the rightful owner of the  trademark, which has been registered in the Republic of China since October 1, 1978; 3) Cymar fraudulently obtained the assailed Certificates of Trademark Registration with full knowledge that Farling is the true owner of the

trademark, which has been registered in the Republic of China since October 1, 1978; 3) Cymar fraudulently obtained the assailed Certificates of Trademark Registration with full knowledge that Farling is the true owner of the  trademark;9 and 4) the issuance of the assailed Certificates of Trademark Registration violates the Paris Convention for the Protection of Intellectual Property (Paris Convention), of which the Philippines is a signatory.10

trademark;9 and 4) the issuance of the assailed Certificates of Trademark Registration violates the Paris Convention for the Protection of Intellectual Property (Paris Convention), of which the Philippines is a signatory.10

Cymar answered that: 1) having used the  trademark since January 5, 1983, it is the actual first user thereof in the Philippines; 2) Farling's Republic of China trademark registration, which covers "various plastic and resinous products and all other commodities belonging to this class," does not specify the particular products covered thereby; thus, it cannot be used as basis to cancel Cymar's trademarks; 3) Farling's Republic of China trademark registration is not protected by the Paris Convention, since it was issued prior to China's accession thereto; 4) under Section 20 of the then-prevailing Trademark Law (Republic Act No. 166), the assailed Certificates of Trademark Registration are prima facie evidence of the validity of the registration and of Cymar's ownership and exclusive right to use the

trademark since January 5, 1983, it is the actual first user thereof in the Philippines; 2) Farling's Republic of China trademark registration, which covers "various plastic and resinous products and all other commodities belonging to this class," does not specify the particular products covered thereby; thus, it cannot be used as basis to cancel Cymar's trademarks; 3) Farling's Republic of China trademark registration is not protected by the Paris Convention, since it was issued prior to China's accession thereto; 4) under Section 20 of the then-prevailing Trademark Law (Republic Act No. 166), the assailed Certificates of Trademark Registration are prima facie evidence of the validity of the registration and of Cymar's ownership and exclusive right to use the  trademark in connection with the goods mentioned in the certificates; and 5) Farling, as a foreign corporation not licensed to do business in the Philippines, has no capacity to sue.11

trademark in connection with the goods mentioned in the certificates; and 5) Farling, as a foreign corporation not licensed to do business in the Philippines, has no capacity to sue.11

On September 27, 1994, upon Farling's motion, the five cases were consolidated on the ground that they involve the same parties, the same subject matter, and the same issues.12

In support of its allegations, Farling offered the following evidence:13 1) shipping documents to prove that its products bearing the  trademark had been exported to numerous countries prior to Cymar's date of first use thereof;14 2) certificates of trademark registration from various countries and samples of print brochures and advertisements, to prove that its

trademark had been exported to numerous countries prior to Cymar's date of first use thereof;14 2) certificates of trademark registration from various countries and samples of print brochures and advertisements, to prove that its  trademark is registered in numerous countries outside of the Republic of China and is well-known throughout the world;15 3) a copy of an undated agreement wherein Farling authorized Cymar to sell the former's products in the Philippines, including those bearing the

trademark is registered in numerous countries outside of the Republic of China and is well-known throughout the world;15 3) a copy of an undated agreement wherein Farling authorized Cymar to sell the former's products in the Philippines, including those bearing the  trademark;16 4) export and shipping documents such as invoices, packing and weight lists, bills of lading, and export permits bearing dates from 1983 to 1993, to prove that said undated agreement was actually implemented, and Farling exported goods to the Philippines for Cymar to distribute;17 5) telex correspondence, other documents, receipts, sales invoices, advertisement contracts, and sample advertisements, to prove that Cymar was merely a distributor of Farling's

trademark;16 4) export and shipping documents such as invoices, packing and weight lists, bills of lading, and export permits bearing dates from 1983 to 1993, to prove that said undated agreement was actually implemented, and Farling exported goods to the Philippines for Cymar to distribute;17 5) telex correspondence, other documents, receipts, sales invoices, advertisement contracts, and sample advertisements, to prove that Cymar was merely a distributor of Farling's  -trademarked products, and was therefore very much aware of the fact that Farling is the registered owner and first user of the

-trademarked products, and was therefore very much aware of the fact that Farling is the registered owner and first user of the  trademark;18 and 6) telex correspondence between Farling and Cymar between 1983 and 1988, to prove that they were coordinating with each other on the promotion of the former's

trademark;18 and 6) telex correspondence between Farling and Cymar between 1983 and 1988, to prove that they were coordinating with each other on the promotion of the former's  -branded products in the Philippines, which were being distributed by the latter.19

-branded products in the Philippines, which were being distributed by the latter.19

On January 1, 1998, the Intellectual Property Code (Republic Act No. 8293, hereinafter referred to as the IPC) took effect. Section 240 of the IPC expressly repealed the old Trademark Law (Republic Act No. 166);20 while Sections 5 and 235 replaced the Bureau of Patents, Trademarks and Technology Transfer with the Intellectual Property Office (IPO).

On December 26, 2002, the Bureau of Legal Affairs of the IPO (BLA-IPO) denied Farling's consolidated petitions.21 The BLA-IPO ruled that Farling's prior use and registration of the  mark in the Republic of China and other foreign countries cannot be considered sources of trademark rights in the Philippines, since: 1) Farling failed to register

mark in the Republic of China and other foreign countries cannot be considered sources of trademark rights in the Philippines, since: 1) Farling failed to register  as a foreign mark under Section 37 of the old Trademark Law;22 and 2) Farling's Republic of China registration lacks sufficient specificity of goods to which the trademark is applicable, as required under the old Trademark Law.23 As the first actual user of the FARLIN mark in the Philippines, Cymar is entitled to the protections afforded by the registration thereof, since the essential element which gives rise to protection of a mark under the old Trademark Law is actual use of such mark in commerce in the Philippines.24 Farling failed to prove actual use of the

as a foreign mark under Section 37 of the old Trademark Law;22 and 2) Farling's Republic of China registration lacks sufficient specificity of goods to which the trademark is applicable, as required under the old Trademark Law.23 As the first actual user of the FARLIN mark in the Philippines, Cymar is entitled to the protections afforded by the registration thereof, since the essential element which gives rise to protection of a mark under the old Trademark Law is actual use of such mark in commerce in the Philippines.24 Farling failed to prove actual use of the  mark in connection with the goods covered by Cymar's certificates of registration, since the goods covered by the export documents presented by Farling refers only to "Chinese Goods."25 The BLA-IPO also refused to accord well-known mark status to Farling's

mark in connection with the goods covered by Cymar's certificates of registration, since the goods covered by the export documents presented by Farling refers only to "Chinese Goods."25 The BLA-IPO also refused to accord well-known mark status to Farling's  trademark, on the ground that majority of Farling's international registrations were issued after Cymar had already obtained the assailed certificates of registration, and such registrations are not sufficient to accord well-known status to Farling's mark.26 Even assuming that Farling's

trademark, on the ground that majority of Farling's international registrations were issued after Cymar had already obtained the assailed certificates of registration, and such registrations are not sufficient to accord well-known status to Farling's mark.26 Even assuming that Farling's  trademark is a well-known mark, the rights under Article 6bis of the Paris Convention apply "only when the later use for identical or similar goods by another is liable to create confusion." However, it has already been demonstrated that Farling's trademark registration does not necessarily cover the same goods covered by Cymar's assailed certificates of registration.27

trademark is a well-known mark, the rights under Article 6bis of the Paris Convention apply "only when the later use for identical or similar goods by another is liable to create confusion." However, it has already been demonstrated that Farling's trademark registration does not necessarily cover the same goods covered by Cymar's assailed certificates of registration.27

Aggrieved, Farling appealed the BLA-IPO ruling to the Director General of the IPO (DG-IPO).28

On October 22, 2003,29 the DG-IPO granted Farling's appeal and ordered the cancellation of Cymar's certificates of trademark registration. The DG-IPO found Farling's evidence sufficient to prove that Cymar is merely an importer or distributor of Farling's trademarked products.30 The DG-IPO also sustained Farling's claim of prior use and ownership of the  trademark since October 1, 1978.31 Likewise, the DG-IPO found no proof that Farling authorized Cymar to register the

trademark since October 1, 1978.31 Likewise, the DG-IPO found no proof that Farling authorized Cymar to register the  mark in the Philippines, or that Cymar is the owner thereof in the country where the goods were imported from; thus, Cymar has no right to register the

mark in the Philippines, or that Cymar is the owner thereof in the country where the goods were imported from; thus, Cymar has no right to register the  mark in its name.32 The evidence presented by Farling is enough to overthrow the prima facie presumption of ownership and exclusive rights created by Cymar's certificates of registration.33 The use of "Chinese goods" as a descriptor in Farling's export documents is irrelevant, for a piece-by-piece scrutiny of said documents reveals that the aforementioned "Chinese goods" actually include products covered by the assailed certificates of registration, such as feeding bottles, nipple funnels, breast relievers, nasal aspirators, safety pins, and cotton buds.34 As a mere distributor and importer, Cymar had no right to register the

mark in its name.32 The evidence presented by Farling is enough to overthrow the prima facie presumption of ownership and exclusive rights created by Cymar's certificates of registration.33 The use of "Chinese goods" as a descriptor in Farling's export documents is irrelevant, for a piece-by-piece scrutiny of said documents reveals that the aforementioned "Chinese goods" actually include products covered by the assailed certificates of registration, such as feeding bottles, nipple funnels, breast relievers, nasal aspirators, safety pins, and cotton buds.34 As a mere distributor and importer, Cymar had no right to register the  trademark; and Farling, as the rightful owner thereof, is entitled to have Cymar's certificates of trademark registration cancelled.

trademark; and Farling, as the rightful owner thereof, is entitled to have Cymar's certificates of trademark registration cancelled.

Cymar appealed the DG-IPO decision to the Court of Appeals (CA) through a petition for review35 under Rule 43,36 which was docketed as CA G.R. SP No. 80350.1aшphi1

On July 26, 2005, the CA rendered a decision37 (2005 CA Decision) affirming the DG-IPO ruling on the basis of the finding that "the import-export business relationship of [Cymar] and [Farling] involving plastic baby products began as early as 1982, prior to [Cymar]'s registration of the trademark  under its own name."38

under its own name."38

On August 15, 2005, Cymar filed a motion for reconsideration, where it presented, for the first time, a document with the caption "Authorization." The document, typewritten on Farling-letterhead stationery, dated May 26, 1988, and signed by Farling's General Manager John Shieh (Shieh), states:

AUTHORIZATION

FARLING INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD., FOR BREVITY, "FARLIN" WHOM I REPRESENT AS THE OWNER HEREBY EXECUTES THIS "AUTHORIZATION" IN COMPLIANCE WITH THE DOCUMENTARY REQUIREMENTS REQUIRED BY THE COPYRIGHT SECTION OF THE PHILIPPINES NATIONAL LIBRARY, IN RELATION WITH CYMAR INTERNATIONAL, INC. APPLICATION FOR COPYRIGHT:

NOTWITHSTANDING THE ABOVE, FARLING INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD. WA[I]VES ANY CLAIM OR RIGHT AGAINST CYMAR INT'L INC. APPLICATION FOR COPYRIGHT BY REASON OF THE INCLUSION OF OUR NAME IN THE BOX DESIGN OF [A]FOR[E]SAID.

BY REASON THER[E]OF, FARLING INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD. WA[I]VES ANY OPPOSITION/OBJECTION FOR CYMAR INT'L INC[.]'S PROPRIETORSHIP OF THE SAID DESIGN IN THE PHILIPPINES, UPON ITS BEING COPYRIGHTED IN THE PHILIPPINES AND THE VALIDITY OF CYMAR INT'L INC'S OF THE [A]FOR[E]SAID APPLICATION.

ISSUED THIS ON THE 26th DAY OF May 1988 AT TAIWAN, R.O.C.39

Cymar argued that the Authorization constitutes a waiver by Farling of its rights over the  mark in the Philippines;40 therefore Cymar had become the owner of the

mark in the Philippines;40 therefore Cymar had become the owner of the  trademark.41 Farling answered that the Authorization could no longer be considered by the CA, as it would amount to a prohibited change of theory on appeal, and was not presented during the administrative cancellation proceedings.42

trademark.41 Farling answered that the Authorization could no longer be considered by the CA, as it would amount to a prohibited change of theory on appeal, and was not presented during the administrative cancellation proceedings.42

Through a resolution dated August 7, 2006, the CA suspended the effectivity of its July 26, 2005 decision and reopened the case for reception of evidence and arguments on the new issues generated by the Authorization.43 During the hearing, Cymar's counsel and corporate secretary testified that the Authorization was not presented before the IPO because Cymar never discussed it with the former counsel who handled the IPO proceedings.44

On May 17, 2007, the CA issued a Resolution45 (2007 CA Resolution) denying Cymar's motion for reconsideration. It ruled that the Authorization does not amount to newly discovered evidence, as Cymar's counsel and corporate secretary admitted that the document was in his custody all along, and could have therefore been discovered through due diligence on Cymar's part. The CA also sustained Farling's argument that the presentation of the Authorization amounts to a belated change of theory on appeal, for Cymar would then be abandoning its claim to first use and original ownership of the  mark and basing its rights on a waiver executed by the first user.46

mark and basing its rights on a waiver executed by the first user.46

On July 5, 2007, Cymar filed a petition for review with the Supreme Court to assail the 2005 CA decision and the 2007 CA resolution. The petition was docketed as G.R. No. 177974. For ease of reference, the proceedings leading up to the filing of G.R. No. 177974 shall hereinafter be referred to as the 1994 Cancellation Case.

2006 Opposition Case (G.R. No. 206121)

On December 18, 2002, during the pendency of the 1994 Cancellation Case, Cymar filed an application for registration of the composite mark47 "FARLIN YOUR BABY IS OUR CONCERN (WITH MOTHER AND CHILD LOGO)"48 with the IPO, for cotton buds, cotton balls, absorbent cotton/cotton roll under class 5, feeding bottles, feeding nipples, pacifiers, teethers, training cup, multistage training cup, spill proof cup, silicone spoon, fork and spoon set, diaper clip, feeding bottle cap, ring, feeding bottle hood under class 10, sterilizer set under class 11, disposable diapers under class 16 and toothbrush, milk powder container, powder case with puff, rack and tongs set, tongs under class 21.49 On December 19, 2006, Farling filed a Verified Notice of Opposition, citing the 2003 DG-IPO Decision as affirmation of its previous claims about the ownership and prior registration of the  trademark, as well as the agreements it entered into with Cymar.50 The case was docketed as IPC No. 14-2006-00188.

trademark, as well as the agreements it entered into with Cymar.50 The case was docketed as IPC No. 14-2006-00188.

On February 28, 2009, the BLA-IPO rendered a decision (First 2009 BLA-IPO Decision) sustaining Farling's opposition.51 Echoing the 2003 DG-IPO Decision, the BLA-IPO found "overwhelming evidence that [Farling] is the owner of the mark by its extensive use and trademark registrations abroad of the mark  on goods which [Cymar] now seeks to register the

on goods which [Cymar] now seeks to register the  mark for";52 and that "[Cymar] has for many years imported the

mark for";52 and that "[Cymar] has for many years imported the  products of [Farling]."53 Thus, as a mere importer, Cymar cannot acquire ownership rights over the

products of [Farling]."53 Thus, as a mere importer, Cymar cannot acquire ownership rights over the  mark or any composite marks based thereon, even if it was the first party to file an application under the IPC. Under Section 138 of the IPC, a certificate of trademark registration is only prima facie evidence of the registrant's ownership and use rights over a trademark.54

mark or any composite marks based thereon, even if it was the first party to file an application under the IPC. Under Section 138 of the IPC, a certificate of trademark registration is only prima facie evidence of the registrant's ownership and use rights over a trademark.54

On appeal by Cymar, the DG-IPO affirmed55 the First 2009 BLA-IPO Decision. The DG-IPO rejected Cymar's claim of forum shopping since the opposition pertains to a mark distinct from the marks cancelled in the proceedings in G.R. No. 177974. The DG-IPO likewise held that Farling's proof of ownership over the  mark and its distribution arrangement with Cymar prevails over the latter's prior registration.56 Cymar elevated the matter to the CA through a Rule 43 petition for review.

mark and its distribution arrangement with Cymar prevails over the latter's prior registration.56 Cymar elevated the matter to the CA through a Rule 43 petition for review.

Through a decision dated March 4, 2013 (2013 CA Decision), the CA denied57 Cymar's petition. The CA affirmed the DG-IPO's ruling, not only on the existence of forum shopping, but also on the substantive issues of the case. The CA found that the DG-IPO's conclusions are supported by substantial evidence, and can no longer be disturbed, given the lack of compelling reasons therefor. Notably, the CA rejected Cymar's waiver argument for the second time. The CA held that the Authorization executed by Farling through Shieh only constitutes a waiver of the copyright over the box design containing Farling's name. The CA reiterated that trademark and copyright are distinct bundles of rights which cannot be interchanged. Thus, the Authorization cannot serve as a source of any trademark rights in favor of Cymar.58

Undeterred, Cymar again elevated59 the matter to the Court, where it was docketed as G.R. No. 206121. For ease of reference, these proceedings which were borne out of IPC No. 14-2006-00188, and which eventually reached the Court as G.R. No. 206121, shall hereinafter be referred to as the 2006 Opposition Case.

2007 Opposition Case (G.R. No. 219072)

On April 23, 2003, while the 1994 Cancellation and 2006 Opposition Cases were still pending with the DG-IPO, Cymar filed an application for registration of the composite mark "FARLIN DISPOSABLE BABY DIAPERS (With Mother & Child Icon)"60 with the IPO, for disposable baby diapers under Class 16 of the International Classification of goods.61 On September 4, 2007, Farling filed a Verified Notice of Opposition, still reiterating its earlier arguments which have been affirmed in the 2005 CA decision and the 2007 CA resolution.62 The case was docketed as Inter Partes Case No. 14-2007-00252.

In a decision dated February 28, 2009 (Second 2009 BLA-IPO Decision), the BLA-IPO sustained63 Farling's opposition and rejected Cymar's application. Relying on the First 2009 BLA-IPO Decision, as affirmed by the 2005 CA decision and the 2007 CA resolution, the BLA-IPO once again found Farling to be the owner and first user of the  mark, and Cymar as a mere importer-distributor. The BLA-IPO thus concluded that "Cymar's "use in commerce of the mark

mark, and Cymar as a mere importer-distributor. The BLA-IPO thus concluded that "Cymar's "use in commerce of the mark  inures to benefit of foreign manufacturer and actual owner Farling."64 Once again, the BLA-IPO rejected Cymar's invocation of the first-to-file rule under Sections 122 and 138 of the IPC. Relying on the conception of a trademark under the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement), as implemented by the IPC, the BLA-IPO ruled that "it is the use of the mark that [gives] rise to ownership of the trademark, which in turn gives the right to the owner to cause its registration and enjoy exclusive use thereof for the goods associated with it."65 It explained that the first-to-file rule cannot be invoked to grant the application of a "first filer" despite the existence of a better right to the trademark sought to be registered. Under the TRIPS Agreement, as implemented by the IPC, "the idea of 'registered owner,'" does not mean that ownership is established by mere registration but that registration merely establishes a presumptive right over ownership. The presumption of ownership yields to superior evidence of actual and real ownership of the trademark and the TRIPS Agreement requirement that no existing prior rights shall be prejudiced."66 In the case at bar, Cymar, despite its status as the "first filer," is not entitled to registration of the mark, because there is proof that it is not the first actual user of the mark; indeed, the record even shows that it is not the first party to have the mark registered anywhere in the world.67

inures to benefit of foreign manufacturer and actual owner Farling."64 Once again, the BLA-IPO rejected Cymar's invocation of the first-to-file rule under Sections 122 and 138 of the IPC. Relying on the conception of a trademark under the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement), as implemented by the IPC, the BLA-IPO ruled that "it is the use of the mark that [gives] rise to ownership of the trademark, which in turn gives the right to the owner to cause its registration and enjoy exclusive use thereof for the goods associated with it."65 It explained that the first-to-file rule cannot be invoked to grant the application of a "first filer" despite the existence of a better right to the trademark sought to be registered. Under the TRIPS Agreement, as implemented by the IPC, "the idea of 'registered owner,'" does not mean that ownership is established by mere registration but that registration merely establishes a presumptive right over ownership. The presumption of ownership yields to superior evidence of actual and real ownership of the trademark and the TRIPS Agreement requirement that no existing prior rights shall be prejudiced."66 In the case at bar, Cymar, despite its status as the "first filer," is not entitled to registration of the mark, because there is proof that it is not the first actual user of the mark; indeed, the record even shows that it is not the first party to have the mark registered anywhere in the world.67

Acting on Cymar's appeal, the DG-IPO rendered a decision68 dated April 23, 2012, affirming the Second 2009 BLA-IPO Decision. Again, the DG-IPO rejected Cymar's claim of forum shopping, since although all the previous Cases also involve a mark containing the  mark, the present case nevertheless involves a composite mark that is distinct from the marks passed upon in the previous cases. Furthermore, Farling explicitly admitted the pendency of G.R. No. 177974 in its verification and certification.69 The DG-IPO held that the evidence it relied upon in the 2003 DG-IPO Decision, as affirmed in the 2005 CA Decision and 2007 CA Resolution and adopted in the First 2009 BLA-IPO Decision, remain relevant and sufficient to prove that Farling is the owner of the

mark, the present case nevertheless involves a composite mark that is distinct from the marks passed upon in the previous cases. Furthermore, Farling explicitly admitted the pendency of G.R. No. 177974 in its verification and certification.69 The DG-IPO held that the evidence it relied upon in the 2003 DG-IPO Decision, as affirmed in the 2005 CA Decision and 2007 CA Resolution and adopted in the First 2009 BLA-IPO Decision, remain relevant and sufficient to prove that Farling is the owner of the  mark and that Cymar is a mere importer of Farling's

mark and that Cymar is a mere importer of Farling's  -trademarked products.70 Cymar cannot rely on the limited scope of its trademark application, since its claim to the present FARLIN (image different from text)-based composite mark71 over disposable baby diapers still overlaps with Farling's product line, which covers the whole class of baby products such as baby bottles, nipples, pacifiers, aspirators, powder puffs, rattles, cotton swabs, funnels, milk containers, among others.72 Cymar sought recourse with the CA.

-trademarked products.70 Cymar cannot rely on the limited scope of its trademark application, since its claim to the present FARLIN (image different from text)-based composite mark71 over disposable baby diapers still overlaps with Farling's product line, which covers the whole class of baby products such as baby bottles, nipples, pacifiers, aspirators, powder puffs, rattles, cotton swabs, funnels, milk containers, among others.72 Cymar sought recourse with the CA.

On June 25, 2015, the CA rendered a decision73 (2015 CA Decision) denying Cymar's petition for review. The CA found that Cymar and Farling had entered into an informal distributorship agreement as early as 1981. This agreement was not reduced to writing; but under said agreement, Farling provided  branded merchandise and promotional materials to Cymar.74 The CA also found that Cymar and Farling actually cooperated in the registration of the "FARLIN and Device" trademark in the Philippines, as Cymar sent application documents which were then accomplished and notarized by Farling. These documents were then delivered to Cymar on the assumption that these will be delivered to Farling's recommended attorneys for filing.75 However, as it turned out, Cymar registered the mark in its own name.76

branded merchandise and promotional materials to Cymar.74 The CA also found that Cymar and Farling actually cooperated in the registration of the "FARLIN and Device" trademark in the Philippines, as Cymar sent application documents which were then accomplished and notarized by Farling. These documents were then delivered to Cymar on the assumption that these will be delivered to Farling's recommended attorneys for filing.75 However, as it turned out, Cymar registered the mark in its own name.76

The CA rejected Cymar's procedural objections to the DG-IPO's ruling. Particularly, the CA ruled that: 1) the DG-IPO ruling adequately states the factual and legal bases therefor;77 2) Cymar failed to prove that the DG-IPO acted with manifest bias and prejudice;78 3) the DG-IPO ruling did not apply res judicata, since it is not applicable to the case;79 4) the IPO rules of procedure do not require parties to make a separate offer of evidence for the purposes required under the IPC;80 5) the submission of mere photocopies of documents is allowed in administrative proceedings where the technical rules of evidence are not binding;81 and 6) the fact that the 1994 Cancellation Case were litigated under the old Trademark Law does not affect the relevance, admissibility, or applicability of the evidence presented therein to the present case, which involves a composite mark based on the  trademark. In fact, the DG-IPO would have offended Cymar's administrative due process rights had it not considered such relevant and applicable evidence.82

trademark. In fact, the DG-IPO would have offended Cymar's administrative due process rights had it not considered such relevant and applicable evidence.82

Turning to the merits of the Second 2009 BLA-IPO Decision as affirmed by the DG-IPO, the CA ruled that the intellectual property adjudicators correctly rejected Cymar's application, as there is clear and convincing evidence on record to support the findings and conclusions of the BLA-IPO and DG-IPO.83 Once again, the CA ruled that the Authorization did not transmit any trademark rights to Cymar, since it only pertains to the copyright over the box design of the  mark. The CA reiterated the distinction between trademark rights and copyright.

mark. The CA reiterated the distinction between trademark rights and copyright.

Still undeterred, Cymar filed another petition for review84 with the Supreme Court, which was docketed as G.R. No. 219072. For ease of reference, these proceedings, which stemmed from Inter Partes Case No. 14-2007-0025, shall be referred to as the 2007 Opposition Case.

2008 Opposition Case (G.R. No. 228802)

On August 22, 2007, still during the pendency of the 1994 Cancellation Case and the 2006 and 2007 Opposition Cases, Cymar filed an application for registration of the mark "FARLIN BLUE BUNNY AND BUNNY DEVICE" with the IPO, thus:85

Cymar's application covered the following goods: sterilizer sets (Class 11); feeding bottles, feeding nipples, pacifiers, teethers, training cup, multi-stage training cup, spill-proof cup, silicone spoon, fork and spoon set[,] diaper clip, feeding bottle cap ring, feeding bottle hood (Class 10); cotton buds, cotton balls, absorbent cotton/cotton roll (Class 05); disposable diapers (Class 16); and toothbrush, milk powder container, powder case with puff, rack and tongs set, and tongs (Class 21).86

On August 26, 2008, Farling filed a Verified Notice of Opposition, still reiterating the arguments it raised in the 1994 Cancellation Case, which were sustained in the 2005 CA Decision.87 In response, Cymar also reiterated the arguments it made in the 1994 Cancellation Case.88 Additionally, it argued that: 1) Farling's opposition does not include a certification against forum shopping, and the certification it belatedly submitted contains a deliberate misrepresentation that G.R. No. 177974 is not related to the present case;89 2) the evidence submitted in the 1994 Cancellation Case are inapplicable to the present case, because the requisites for trademark registration are different under the IPC and the old Trademark Law;90 3) Farling's theory that the name "FARLIN" in the  mark is a derivation of its corporate name is incorrect, because the letters F, A, R, L, I, and N which constitute the name "FARLIN" in the

mark is a derivation of its corporate name is incorrect, because the letters F, A, R, L, I, and N which constitute the name "FARLIN" in the  mark are not the dominant feature of the corporate name "Farling"; 4) pursuant to the first-to-file rule under the IPC, Cymar has the better right to marks derived from the "FARLIN" name, since it was the first to register such a mark in the Philippines;91 5) assuming that Farling's Republic of China trademark registration may be recognized in this jurisdiction, such registration has already expired in 1988;92 6) the products covered by the "FARLIN BLUE BUNNY AND BUNNY DEVICE" mark sought to be registered are different from the registration classes and products claimed by Farling;93 7) apart from being the first registrant and user, Cymar is also the party primarily responsible for promoting the brand reputation of the "FARLIN" name in the Philippines;94 8) through the Authorization, Farling waived any intellectual property right it had over the name "FARLIN";95 and 9) the documents submitted by Farling are inadmissible because they are not certified true copies, not covered by affidavits of witnesses, and were not offered separately for purposes of the present case, contrary to the IPO's regulations on inter partes cases.96 The case was docketed as Inter Partes Case No. 14-2008-00186.

mark are not the dominant feature of the corporate name "Farling"; 4) pursuant to the first-to-file rule under the IPC, Cymar has the better right to marks derived from the "FARLIN" name, since it was the first to register such a mark in the Philippines;91 5) assuming that Farling's Republic of China trademark registration may be recognized in this jurisdiction, such registration has already expired in 1988;92 6) the products covered by the "FARLIN BLUE BUNNY AND BUNNY DEVICE" mark sought to be registered are different from the registration classes and products claimed by Farling;93 7) apart from being the first registrant and user, Cymar is also the party primarily responsible for promoting the brand reputation of the "FARLIN" name in the Philippines;94 8) through the Authorization, Farling waived any intellectual property right it had over the name "FARLIN";95 and 9) the documents submitted by Farling are inadmissible because they are not certified true copies, not covered by affidavits of witnesses, and were not offered separately for purposes of the present case, contrary to the IPO's regulations on inter partes cases.96 The case was docketed as Inter Partes Case No. 14-2008-00186.

On December 22, 2009, the BLA-IPO rendered a decision97 (Third 2009 BLA-IPO Decision) sustaining Farling's opposition. The BLA-IPO again took cognizance of the results of the 1994 Cancellation Case and the evidence presented therein; thus, it found that Cymar's previous registrations of the  mark have already been cancelled, and that Farling has registered the mark in the Republic of China for various classes of products.98 The BLA-IPO held that the first-to-file rule only creates a prima facie presumption of ownership over a mark, which may be overturned by evidence to the contrary. In the case at bar, Farling's evidence, which proves that Cymar was a mere importer of Farling's

mark have already been cancelled, and that Farling has registered the mark in the Republic of China for various classes of products.98 The BLA-IPO held that the first-to-file rule only creates a prima facie presumption of ownership over a mark, which may be overturned by evidence to the contrary. In the case at bar, Farling's evidence, which proves that Cymar was a mere importer of Farling's  -marked products, sufficiently rebuts the prima facie presumption created by the first-to-file rule.99 As the actual first user and owner of the

-marked products, sufficiently rebuts the prima facie presumption created by the first-to-file rule.99 As the actual first user and owner of the  mark, Cymar's efforts and expenditures in building goodwill for the brand should inure to Farling.100

mark, Cymar's efforts and expenditures in building goodwill for the brand should inure to Farling.100

On September 3, 2012, the DG-IPO dismissed101 Cymar's appeal and affirmed the Third 2009 BLA-IPO Decision. The DG-IPO brushed aside Cymar's claim of forum shopping, since the present case involves marks which are distinct from those passed upon in the previous cancellation cases.102 The DG-IPO also upheld the BLA-IPO's findings on the true ownership of the  mark; and added that the products covered by the "FARLIN BLUE BUNNY AND BUNNY DEVICE" mark sought to be registered are almost identical to the products covered by Farling's marks, since the claims of both parties cover the same general class of baby products. Allowing the registration of the "FARLIN BLUE BUNNY AND BUNNY DEVICE" mark will, in effect, prevent Farling from using its

mark; and added that the products covered by the "FARLIN BLUE BUNNY AND BUNNY DEVICE" mark sought to be registered are almost identical to the products covered by Farling's marks, since the claims of both parties cover the same general class of baby products. Allowing the registration of the "FARLIN BLUE BUNNY AND BUNNY DEVICE" mark will, in effect, prevent Farling from using its  mark on its own products, and is likely to create confusion among consumers as to the source or origin of the products.103

mark on its own products, and is likely to create confusion among consumers as to the source or origin of the products.103

Still undeterred, Cymar elevated the matter again to the CA.

In a decision dated October 12, 2016 (2016 CA Decision),104 the CA upheld the DG-IPO's conclusions and denied Cymar's recourse for a fourth time. In rejecting Cymar's claim of difference of product coverage, the CA upheld the BLA-IPO's finding that Farling actually shipped nipples, cotton swabs, milk powder containers, feeding and training bottles, and sterilization sets to Cymar in 1983.105 Thus, Cymar cannot claim difference of product coverage, since these products are covered by the "FARLIN BLUE BUNNY AND BUNNY DEVICE" mark it seeks to register in the present case.

Upon the denial106 of its motion for reconsideration, Cymar again elevated the matter to the Supreme Court, where it was docketed as G.R. No. 228802. For ease of reference, these proceedings, which stemmed from Inter Partes Case No. 14-2008-00186, shall be referred to as the 2008 Opposition Case.

Proceedings before the Supreme Court

On March 17, 2008, the Court ordered the parties to submit their respective memoranda in G.R. No. 177974.107 Through resolutions dated July 24, 2013,108 February 29, 2016,109 and April 23, 2018,110 Cymar's petitions were consolidated and assigned to the member-in-charge of G.R. No. 177974. On July 9, 2014, after the consolidation of G.R. Nos. 177974 and 206121, the Court ordered the parties to submit their respective memoranda for the said consolidated cases.111 The parties also filed their respective pleadings in G.R. Nos. 219072 and 228802.112

Issues

The arguments presented in the parties' ponderous tomes of pleadings are distillable into the following issues:

1) Whether the 1994 Cancellation Case involving the basic  mark constitutes res judicata as against the 2006, 2007, and 2008 Opposition Cases;

mark constitutes res judicata as against the 2006, 2007, and 2008 Opposition Cases;

2) Whether Farling committed forum shopping when it initiated the 2006, 2007, and 2008 Opposition Cases;

3) Whether the exhibits submitted by Farling in the 1994 Cancellation Case, especially the Republic of China trademark registration, are admissible in evidence;

4) Whether the evidence in the 1994 Cancellation Case may be admitted and appreciated in the 2006, 2007, and 2008 Opposition Cases;

5) In G.R. No. 219072, whether the DG-IPO's affirmance of the Second 2009 BLA-IPO Decision is compliant with Article VIII, Section 14 of the Constitution;

6) Whether Farling's trademark registrations and prior use of the  mark in foreign jurisdictions may be recognized in the Philippines even without registration in its own name;

mark in foreign jurisdictions may be recognized in the Philippines even without registration in its own name;

7) Whether Cymar, as the first registrant of the disputed marks, should be considered the rightful owner thereof, pursuant to the first-to-file rule.

8) Whether Cymar had the capacity distributed  -marked products in the Philippines; and

-marked products in the Philippines; and

9) Whether the Authorization operated to transfer trademark rights from Farling to Cymar.

These issues all boil down to a single question: who between Cymar and Farling has the right to use and register the  mark and its derivatives in this jurisdiction?

mark and its derivatives in this jurisdiction?

The Court's Ruling

I. Forum shopping and res judicata

Cymar argues that Farling deliberately failed to disclose the pendency of the 1994 Cancellation Case in its December 2006 opposition, which initiated the 2006 Opposition Case.113 Cymar asserts that the pendency of the 1994 Cancellation Case should have been disclosed in the 2006 Opposition Case, because the former constitutes res judicata as to the latter. Cymar argues that the 1994 Cancellation Case and the 2006 Opposition Case involve the same parties, rights, reliefs, and issues. By omitting the pendency of the 1994 Cancellation Case in its 2006 opposition, Farling not only violated the rule on certification against forum shopping; but also committed willful and deliberate forum shopping.114 Cymar further faults the DG-IPO for allowing Farling's 2006, 2007, and 2008 oppositions on the ground that these were filed merely to prevent the registration of the FARLIN-derived marks. Cymar argues that there is another plain, speedy, and adequate remedy to prevent such registration other than the filing of an opposition, in the form of a request for suspension under Rule 617 of the Rules on Registration of Trademarks.115 In G.R. No. 219072, Cymar points out that in the 2007 Opposition Case, the BLA-IPO and DG-IPO both rejected its argument on res judicata even as they relied on the 2005 CA Decision and the 2007 CA Resolution to reject its application for registration of the "FARLIN DISPOSABLE BABY DIAPERS (With Mother & Child Icon)" mark.116

Farling ripostes that the issues in the 1994 Cancellation Case and 2006 Opposition Case are different but intertwined, in that the two cases both involve the true ownership of the basic  mark, but the 2006 Opposition Case involves a different mark which was formed from the basic FARLIN mark.117 Thus, the cancellation of the

mark, but the 2006 Opposition Case involves a different mark which was formed from the basic FARLIN mark.117 Thus, the cancellation of the  registrations involved in the 1994 Cancellation Case will not necessarily result in the denial of the registration of the "FARLIN YOUR BABY IS OUR CONCERN (WITH MOTHER AND CHILD LOGO)" sought to be registered in the 2006 Opposition Case, and vice versa.118 Farling further asserts that it did not commit forum shopping when it filed the 2006 Opposition Case because it involves a different cause of action from the 1994 Cancellation Case. There being no identity of issues or causes of action between the 1994 Cancellation Case and the subsequent cancellation cases, Farling neither violated the rule on certification against forum shopping nor committed actual forum shopping.

registrations involved in the 1994 Cancellation Case will not necessarily result in the denial of the registration of the "FARLIN YOUR BABY IS OUR CONCERN (WITH MOTHER AND CHILD LOGO)" sought to be registered in the 2006 Opposition Case, and vice versa.118 Farling further asserts that it did not commit forum shopping when it filed the 2006 Opposition Case because it involves a different cause of action from the 1994 Cancellation Case. There being no identity of issues or causes of action between the 1994 Cancellation Case and the subsequent cancellation cases, Farling neither violated the rule on certification against forum shopping nor committed actual forum shopping.

Heirs of Mampo v.1aшphi1 Morada119 provides a comprehensive but succinct statement of the concept of forum shopping and its relation to the concept of res judicata:

Forum shopping is committed by a party who institutes two or more suits involving the same parties for the same cause of action, either simultaneously or successively, on the supposition that one or the other court would make a favorable disposition or increase a party's chances of obtaining a favorable decision or action. It is an act of malpractice that is prohibited and condemned because it trifles with the courts, a uses their processes, degrades the administration of justice, and adds to the already congested court dockets.

At present, the rule against forum shopping is embodied in Rule 7, Section 5 of the Rules [of Court] x x x.

There are two rules on forum shopping, separate and independent from each other, provided in Rule 7, Section 5: 1) compliance with the certificate of forum shopping and 2) avoidance of the act of forum shopping itself.

To determine whether a party violated the rule against forum shopping, the most important factor is whether the elements of litis pendentia are present, or whether a final judgment in one case will amount to res judicata in another. Otherwise stated, the test for determining forum shopping is whether in the two (or more) cases pending, there is identity of parties, rights or causes of action, and reliefs sought.

Hence, forum shopping can be committed in several ways: (1) filing multiple cases based on the same cause of action and with the same prayer, the previous case not having been resolved yet (where the ground for dismissal is litis pendentia); (2) filing multiple cases based on the same cause of action and the same prayer, the previous case having been finally resolved (where the ground for dismissal is res judicata); and (3) filing multiple cases based on the same cause of action but with different prayers (splitting of causes of action, where the ground for dismissal is also either litis pendentia or res judicata).

These tests notwithstanding, what is pivotal is the vexation brought upon the courts and the litigants by a party who asks different courts to rule on the same or related causes and grant the same or substantially the same reliefs and, in the process, creates the possibility of conflicting decisions being rendered by the different fora upon the same issues.

Forum shopping is a ground for summary dismissal of both initiatory pleadings without prejudice to the taking of appropriate action against the counsel or party concerned. This is a punitive measure to those who trifle with the orderly administration of justice.120

The gravamen of forum shopping is the filing of multiple cases based on the same cause of action, resulting in vexation to the parties and confusion in the judicial system. We find that this situation does not obtain in the present case since the four cases a quo arise from distinct causes of action.

For easy reference, the disputed marks and their particulars are reproduced in the table below:

|

1994 Cancellation Case |

2006 Opposition Case |

2007 Opposition Case |

2008 Opposition Case |

| Mark/s involved |

FARLIN and FARLIN LABEL (with colors) |

FARLIN YOUR BABY IS OUR CONCERN (With Mother and Child Logo) |

FARLIN DISPOSABLE BABY DIAPERS (With Mother & Child Icon) |

FARLIN BLUE BUNNY AND BUNNY DEVICE |

| Pictographic representation of the mark/s |

|

|

|

|

| Products covered |

FARLIN:

feeding bottles, nipples (rubber and silicon), funnel, nasal aspirator, breast reliever, ice bag and training bottles, diaper clips, t-shirts, sando, tie-side and other baby clothes

FARLIN LABEL with colors pink and blue: diaper clip

FARLIN LABEL with colors blue, green, pink, yellow and gray: cotton buds. |

cotton buds, cotton balls, absorbent cotton/cotton roll (Class 5), feeding bottles, feeding nipples, pacifiers, teethers, training cup, multistage training cup, spill proof cup, silicone spoon, fork and spoon set, diaper clip, feeding bottle cap, ring, feeding bottle hood (Class 10), sterilizer set (Class 11), disposable diapers (Class 16), and toothbrush, milk powder container, powder case with puff, rack and tongs set, tongs (Class 21). |

disposable baby diapers (Class 16) |

sterilizer sets (Class 11); feeding bottles, feeding nipples, pacifiers, teethers, training cup, multi stage training cup, spill proof cup, silicone spoon, fork and spoon set diaper clip, feeding bottle cap ring, feeding bottle hood (Class 10); cotton buds, cotton balls, absorbent cotton/cotton roll (Class 5); disposable diapers (Class 16); and toothbrush, milk powder container, powder case with puff, rack and tongs set, and tong (Class 21). |

It is apparent that all the marks include the word "FARLIN"; and three of them use the same  stylization. Likewise, the product coverage of all four marks can be classified under one category: infant care products. In fact, the product coverage of the FARLIN and FARLIN LABEL, FARLIN YOUR BABY IS OUR CONCERN (With Mother and Child Logo), and FARLIN BLUE BUNNY AND BUNNY DEVICE marks is virtually the same. Likewise, as Farling itself admits, the true ownership of the

stylization. Likewise, the product coverage of all four marks can be classified under one category: infant care products. In fact, the product coverage of the FARLIN and FARLIN LABEL, FARLIN YOUR BABY IS OUR CONCERN (With Mother and Child Logo), and FARLIN BLUE BUNNY AND BUNNY DEVICE marks is virtually the same. Likewise, as Farling itself admits, the true ownership of the  mark and the circumstances of its commercial relationship with Cymar were commonly raised in all four cancellation cases.

mark and the circumstances of its commercial relationship with Cymar were commonly raised in all four cancellation cases.

Indeed, there are issues of fact and law common to the 1994 Cancellation Case, and the 2006, 2007, and 2008 Opposition Cases; nevertheless, res judicata or litis pendentia cannot arise because the cases are founded on different causes of action. A cause of action is the act or omission by which a party violates another's right.121 On one hand, the cause of action in the 1994 Cancellation Case is the registration of the basic  mark and FARLIN LABEL with respect to the products covered by Trademark Certificate of Registration Nos. 48144, 50483, 54569, 8348, and 8328, in violation of Farling's alleged rights over the mark arising from prior use and registration in its home country. On the other hand, the causes of action in the subsequent cancellation cases are based on Cymar's attempts to register distinct derivatives of the basic FARLIN mark for various products during the pendency of the 1994 Cancellation Case which was decided by the IPO in favor of Farling. Thus, as Farling and the IPO correctly point out, each of the four cases is based on a distinct cause of action arising from the registration of a distinct, albeit derivative, trademark. Farling was justified in filing the 2006, 2007, and 2008 cancellation cases so that its victory before the IPO and the CA in the 1994 Cancellation Case may not rendered nugatory by the mere expedient of Cymar registering marks that 'incorporate the FARLIN mark that has already been adjudicated in Farling's favor.

mark and FARLIN LABEL with respect to the products covered by Trademark Certificate of Registration Nos. 48144, 50483, 54569, 8348, and 8328, in violation of Farling's alleged rights over the mark arising from prior use and registration in its home country. On the other hand, the causes of action in the subsequent cancellation cases are based on Cymar's attempts to register distinct derivatives of the basic FARLIN mark for various products during the pendency of the 1994 Cancellation Case which was decided by the IPO in favor of Farling. Thus, as Farling and the IPO correctly point out, each of the four cases is based on a distinct cause of action arising from the registration of a distinct, albeit derivative, trademark. Farling was justified in filing the 2006, 2007, and 2008 cancellation cases so that its victory before the IPO and the CA in the 1994 Cancellation Case may not rendered nugatory by the mere expedient of Cymar registering marks that 'incorporate the FARLIN mark that has already been adjudicated in Farling's favor.

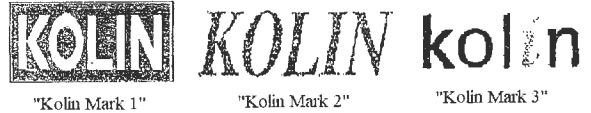

We also note that Cymar's argument is somewhat similar to the one discussed in the recent case of Kolin Electronics Co., Inc. v. Kolin Philippines International, Inc. (Kolin Electronics),122 which, like this case, also involved a clash of distinct trademarks based on the same coined word:

In fine, the Court ruled that the prior adjudication involving Kolin Marks 1 and 2, referred to in the decision as the Taiwan Kolin case, does not constitute res judicata as to the subsequent dispute involving Kolin Marks 2 and 3, because

[b]ased on the facts, the subject matter in this case [involving Kolin Marks 2 and 3 and the Taiwan Kolin case are different. A subject matter is the item with respect to which the controversy has arisen, or concerning which the wrong has been done, and it is ordinarily the right, the thing, or the contract under dispute. In this case, the item to which the controversy has arisen or the thing under dispute is KPII's  mark, while in the Taiwan Kolin case, the subject matter is TKC's

mark, while in the Taiwan Kolin case, the subject matter is TKC's  mark.

mark.

The cause of action in the Taiwan Kolin case is also different from the cause of action in the case at bar. Rule 2, Section 2 of the Rules of Court defines a cause of action as an act or omission by which a party violates the right of another. In the Taiwan Kolin case, the cause of action was TKC's act of filing Trademark Application No. 4-1996-106310 for  , which allegedly violated KECI's rights because confusion would be likely among consumers if TKC's trademark application were to be given due course. In contrast, in the case at bar, the cause of action is KPII's act of filing Trademark Application No. 4-2006-010021 for

, which allegedly violated KECI's rights because confusion would be likely among consumers if TKC's trademark application were to be given due course. In contrast, in the case at bar, the cause of action is KPII's act of filing Trademark Application No. 4-2006-010021 for  .

.

Thus, there is no bar by prior judgment in this case.123

Unlike Kolin Electronics, which involved marks held by three different parties, the case at bar is only between Cymar and Farling: However, the same principle animates both cases: that each application for a distinct trademark is a distinct cause of action, even if the mark applied for is derivative of, or, as in Kolin Electronics, aurally similar, to another mark previously adjudicated to a party. Kolin Electronics explains:

What is involved in this case now before the Court is a new trademark application by KPII which means that it is going through an entirely new process of determining registrability. There is nothing under the law which mandates that registered trademark owners and/or their privies may automatically register all similar marks, despite allegations of "damage" by opposers.

Since new trademark applications are attempts to claim new exclusive rights, there will necessarily be new nuances of "damage", even if the same parties are involved, and the Court should carefully consider these nuances in deciding to give due course to the application. There are new issues on "damage" to KECI here, not decided in the Taiwan Kolin case, which affect the registrability of KPII's application for  and which must be resolved by the Court.124

and which must be resolved by the Court.124

Since Farling did not commit forum shopping when it initiated the 2006, 2007, and 2008 Opposition Cases, we also absolve it from the charge of noncompliance with the rule on certification against forum shopping. Rule 7, Section 5 of the Rules of Court requires the pleader to state the non-existence, or the existence and status of, "any action or filed any claim involving the same issues in any court, tribunal or quasi-judicial agency". Here, Farling correctly points out that it disclosed the pendency of the 1994 Cancellation Case in its 2006 opposition, even if it qualified that "(t)here is no identity of issues between the instant opposition case (i.e., the 2006 Opposition Case) and the [1994 Cancellation Case] now on petition for review by Cymar with this Honorable Court docketed as G.R. No. 177974."125 What matters is that Farling disclosed the existence and status of the related case, so that the court or tribunal may render a proper ruling on whether forum shopping was committed. As it turns out, Farling could not have committed forum shopping.

Cymar also errs in claiming that suspension of action under Rule 617 of the Trademark Rules is the appropriate remedy for Farling to prevent the registration of Cymar's trademarks. The suspension of action under that provision can only be granted upon written request of the applicant:

RULE 617. Suspension of action by the Bureau. Action by the Bureau may be suspended upon written request of the applicant for good and sufficient cause, for a reasonable time specified and upon payment of the required fee. The Examiner may grant only one suspension, and any further suspension shall be subject to the approval of the Director. An Examiner's action, which is awaiting a response by the applicant, shall not be subject to suspension. (Emphasis, italics, and underscoring supplied)

Obviously, Farling cannot avail of this remedy, because it is not the party-applicant in the trademark registration cases herein.

II. Admissibility and appreciability of evidence presented in the 1994 Cancellation Case

Cymar next argues that Farling's Republic of China Trademark Registration has no probative value because it was not presented and authenticated pursuant to the provisions of the Rules of Court on original documents and public documents.126 Cymar further argues that the evidence in the 1994 Cancellation Case should not have been admitted and appreciated in the subsequent cancellation cases, for the following reasons: 1) the evidence presented by Farling in the 2006 and subsequent cancellation cases are uncertified photocopies of the evidence it presented in the 1994 Cancellation Case;127 2) said uncertified photocopies were admitted by the IPO without re-identification or comparison with the exhibits in the 1994 Cancellation Case (as required under the Rules of Court and the IPO's own rules of procedure), or attestation from the Supreme Court, where G.R. No. 177974 is pending;128 and 3) the IPO's decision to take official notice of the evidence in the 1994 Cancellation Case has no legal basis.129

Farling counters that the common admission and application of its evidence to all the cancellation cases is consistent with administrative due process. It argues that the IPO rules on trademark cancellation cases adverted to by Cymar allows the IPO to "adopt such mode of proceedings consistent with the requirements of fair play and conducive to the just, speedy and inexpensive disposition of cases and which will give the Bureau the greatest possibility to focus on the contentious issues before it."130 The recompilation and re-submission of the original documents for every cancellation case, as demanded by Cymar, will entail tremendous costs in terms of time, personnel, administrative fees, and other costs, considering that the documents have to be compiled from all over the world.131 Farling further argues that Cymar cannot claim deprivation of due process because: 1) it could have moved for a comparison of the photocopied documents; and 2) it was able to cross-examine the witness who presented Farling's documentary evidence in the cancellation cases.132 Accusing Cymar of duplicitous resort to technicalities, Farling claims that Cymar also asked the IPO to take judicial notice of the photocopies of the original documents it submitted in the earlier cancellation cases.133 At any rate, Farling argues that the IPO's rulings on the admissibility of the parties' evidence are sanctioned by Chapter 3, Book VII, Section 12 of the Administrative Code of 1987, which lays down general rules of evidence in administrative proceedings.134 Finally, Farling argues that the IPO rules on trademark cancellation cases do not require a formal offer of evidence; rather, all that is necessary is that a verified opposition including witness affidavits and documentary evidence be submitted within the period to file an opposition, which Farling did, with the sanction of the IPO and the CA.135

II.A. Non-technical character of IPO inter partes proceedings

The IPO is an administrative agency vested with quasi-judicial powers over disputes involving intellectual property rights. Sections 2 and 5.1 of the IPC provide in part:

SECTION 2. Declaration of State Policy. x x x

It is also the policy of the State to streamline administrative procedures of registering patents, trademarks and copyright, to liberalize the registration on the transfer of technology, and to enhance the enforcement of intellectual property rights in the Philippines.

SECTION 5. Functions of the Intellectual Property Office (IPO). 5.1. To administer and implement the State policies declared in this Act, there is hereby created the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) which shall have the following functions:

b) Examine applications for the registration of marks, geographic indication, integrated circuits;

x x x x

f) Administratively adjudicate contested proceedings affecting intellectual property rights;

x x x x

Clearly, proceedings before the IPO are administrative in nature; they are therefore governed by the principles and doctrines of the law on administrative adjudication.136 One of these long-standing principles is that administrative agencies are not bound by the technical rules of procedure that are usually applicable in courts of law.137

The remedies of trademark registration opposition and cancellation are governed by the IPO-issued Regulations on Inter Partes Proceedings (RIPP), which has been amended several times since it took effect in 1998.138 With respect to the strict application of technical rules of procedure in the introduction and appreciation of evidence in inter partes cases, Rule 2, Section 6 of the original 1998 version of the RIPP provided that:

Section 6. Rules of procedure to be followed in the conduct of hearing of inter partes cases. In the conduct of hearing of inter partes cases, the rules of procedure herein contained shall be primarily applied. The Rules of Court, unless inconsistent with these rules, may be applied in suppletory character, provided, however, that the Director or Hearing Officer shall not be bound by the strict technical rules of procedure and evidence therein contained but may adopt, in the absence of any applicable rule herein, such mode of proceedings which is consistent with the requirements of fair play and conducive to the just, speedy and inexpensive disposition of cases, and which will give the Bureau the greatest possibility to focus on the technical grounds or issues before it.

The RIPP was subsequently amended by Office Order Nos. 18 (1998), 12 (2002), and 79 (2005), by which time Rule 2, Section 6 of the original 1998 version was amended and became Rule 2, Section 5:

Section 5. Rules of Procedure to be followed in the conduct of hearing of Inter Partes cases. The rules of procedure herein contained primarily apply in the conduct of hearing of Inter Partes cases. The Rules of Court may be applied suppletorily. The Bureau shall not be bound by strict technical rules of procedure and evidence but may adopt, in the absence of any applicable rule herein, such mode of proceedings which is consistent with the requirements of fair play and conducive to the just, speedy and inexpensive disposition of cases, and which will give the Bureau the greatest possibility to focus on the contentious issues before it.

The Court applied this 2005 version in Birkenstock Orthopaedie GmbH and Co. KG v. Phil. Shoe Expo Marketing Corp.139 (Birkenstock), which involved the same situation in the case at bar: a party in an opposition proceeding submitting photocopies of evidence used in an earlier cancellation proceeding. We sustained the admission into evidence of the photocopies, viz.:

It is well-settled that "the rules of procedure are mere tools aimed at facilitating the attainment of justice, rather than its frustration. A strict and rigid application of the rules must always be eschewed when it would subvert the primary objective of the rules, that is, to enhance fair trials and expedite justice. Technicalities should never be used to defeat the substantive rights of the other party. Every party-litigant must be afforded the amplest opportunity for the proper and just determination of his cause, free from the constraints of technicalities." "Indeed, the primordial policy is a faithful observance of [procedural rules], and their relaxation or suspension should only be for persuasive reasons and only in meritorious cases, to relieve a litigant of an injustice not commensurate with the degree of his thoughtlessness in not complying with the procedure prescribed." This is especially true with quasi-judicial and administrative bodies, such as the IPO, which are not bound by technical rules of procedure. On this score, Section 5 of the [RIPP] provides:

x x x x

In the case at bar, while petitioner submitted mere photocopies as documentary evidence in the Consolidated Opposition Cases, it should be noted that the IPO had already obtained the originals of such documentary evidence in the related Cancellation Case earlier filed before it. Under this circumstance and the merits of the instant case as will be subsequently discussed, the Court holds that the IPO Director General's relaxation of procedure was a valid exercise of his discretion in the interest of substantial justice.140

Office Order No. 99, series of 2011 refashioned the provision into a suppletory invocation of the Rules of Court:

Section 5. Applicability of the Rules of Court. - In the absence of any applicable rules, the Rules of Court may be applied in suppletory manner.

Office Order No. 99, series of 2011 also introduced the following provision as Rule 2, Section 14:

Section 14. Introduction of evidence forming part of the records of other cases. - A party, through an appropriate motion and payment of applicable fees, may submit as documentary evidence those which already form part of the records of other cases, including those filed in the BLA, the regular courts, and/or other tribunals. For this purpose, documentary evidence and affidavits of witnesses in lieu of the originals must be secured from and certified by the appropriate official or personnel of the BLA, the court or tribunal in possession of the records. In case of object evidence in possession of the BLA, the court or other tribunal which forms part of the records of a case, photographs, video or faithful representations thereof in other media may be submitted, if accompanied by an appropriate certification and attestation from the appropriate official or personnel of the BLA, court or tribunal.

Despite the amendments introduced by Office Order No. 99, series of 2011 and the previous aforementioned IPO Office Orders, the Court in Palao v. Florentino III International, Inc.141 still relied on the original 1998 version of Rule 2, Section 6 of the RIPP to reinstate an appeal from a BLA-IPO decision which the DG-IPO dismissed for lack of proof of authority of counsel to sign the required verification and certification against forum shopping. Notably, the assailed DG-IPO order was issued in 2008, before the amendments under Office Order No. 99, series of 2011 were introduced:142

These requirements notwithstanding, the Intellectual Property Office's own Regulations on Inter Partes Proceedings (which governs petitions for cancellations of a mark, patent, utility model, industrial design, opposition to registration of a mark and compulsory licensing, and which were in effect when respondent filed its appeal) specify that the Intellectual Property Office "shall not be bound by the strict technical rules of procedure and evidence."

Rule 2, Section 6 of these Regulations provides:

x x x x

This rule is in keeping with the general principle that administrative bodies are not strictly bound by technical rules of procedure:

[A]dministrative bodies are not bound by the technical niceties of law and procedure and the rules obtaining in courts of law. Administrative tribunals exercising quasi-judicial powers are unfettered by the rigidity of certain procedural requirements, subject to the observance of fundamental and essential requirements of due process in justiciable cases presented before them. In administrative proceedings, technical rules of procedure and evidence are not strictly applied and administrative due process cannot be fully equated with due process in its strict judicial sense.143

The latest amendments to the RIPP's provisions on the introduction and appreciation of evidence were introduced by Office Order No. 68 (2014), which amended Rule 2, Section 7 by allowing the attachments of photocopies as evidentiary attachments to oppositions; and by Memorandum Circular No. 16-007, which added provisions on modes of service to Rule 2, Section 5, and renumbered Rule 2, Section 14 thereof to Rule 2, Section 15. Thus, the current version of the RIPP provisions on the introduction and appreciation of evidence read:

[Rule 2,] Section 5. Modes of Service; Applicability of the Rules of Court.

x x x x

(b) In the absence of any applicable rules, the Rules of Court may be applied in suppletory manner.

[Rule 2,] Section 7. Filing Requirements for Opposition and Petition. x x x

(b) The opposer or petitioner shall attach to the opposition or petition the affidavits of witnesses, documentary or object evidence, which must be duly-marked starting from Exhibit "A", and other supporting documents mentioned in the notice of opposition or petition together with the translation in English, if not in the English language. The verification and certification of non-forum shopping as well as the documents showing the authority of the signatory or signatories thereto, affidavits and other supporting documents, if executed and notarized abroad, must have been authenticated by the appropriate Philippine diplomatic or consular office. The execution and authentication of these documents must have been done before the filing of the case. For purposes of filing an opposition, however, the authentication may be secured after the filing of the case provided that the execution of the documents aforementioned are done prior to such filing and provided further, that the authentication must be submitted before the issuance of the order of default or conduct of the preliminary conference under Section 14 of this Rule.

(c) For the purpose of the filing of the opposition, the opposer may attach, in lieu of the originals or certified copies, photocopies of the documents mentioned in the immediately preceding paragraph, as well as photographs of the object evidence, subject to the presentation or submission of the originals and/or certified true copies thereof under Sections 14 and 15 of this Rule.

[Rule 2,] Section 15. Introduction of evidence forming part of the records of other cases. A party, through an appropriate motion and payment of applicable fees, may submit as documentary evidence those which already form part of the records of other cases, including those filed in the BLA, the regular courts, and/or other tribunals. For this purpose, documentary evidence and affidavits of witnesses in lieu of the originals must be secured from and certified by the appropriate official or personnel of the BLA, the court or tribunal in possession of the records. In case of object evidence in possession of the BLA, the court or other tribunal which forms part of the records of a case, photographs, video or faithful representations thereof in other media may be submitted, if accompanied by an appropriate certification and attestation from the appropriate official or personnel of the BLA, court or tribunal.

[Rule 2,] Section 17. Quantum of evidence required. Inter Partes Proceedings is essentially an administrative proceedings. [sic] Hence, the quantum of evidence required is substantial evidence. The Bureau shall decide the case on the basis of the pleadings, the records and the evidence submitted, and if appropriate, on matters which may be taken up by judicial notice. (Emphases and underlining supplied)

In the recent case of Kolin Electronics Co., Inc. v. Taiwan Kolin Corp. Ltd.144 (Taiwan Kolin), we sustained the BLA and the DG-IPO's dismissal of the opposition for failure to attach original documents thereto. Although we recognized the non-binding character of technical rules in IPO proceedings, we approvingly quoted the IPO's finding that the oppositor "failed to give any justifiable cause or compelling reason" to invoke such non-binding character:

First, TKCL's claim that its non-compliance with the [RIPP] was due to the fact that it had two Opposition cases and was confused as to which case the original documents should be submitted to, can hardly be considered a justifiable and compelling reason. If the Opposition against Class 35 TM Application (MNO 2008-065) for the use of "www.kolin.ph," were that important, TKCL should have at least submitted with the BLA-IPO even just a signed original or certified true copy of the documents in its Opposition. TKCL could have indicated in the other Opposition case, MNO 2008-064, that the originals were submitted in Opposition case, MNO 2008-065, and thereafter made a reservation for its belated filing. But it neglected to do so.

Second, TKCL's admission that it made a reasonable attempt in complying with the [RIPP], and failed only in ''adequately informing this Honorable Office of the availability of original exhibits . . .," clearly reveals that the documents in original form were already at its disposal. Yet, it never bothered to attach the same to its Opposition, and held on to its erroneous interpretation of the Regulations.

Third, TKCL's claim that it had difficulty in securing the "original copies of its documentary exhibits" since the same were kept in its principal address located in Taipei, Taiwan and that it failed "through inadvertence . . . to indicate in both verified oppositions that 'original copies are available for immediate submission or comparison at the proper time,"' are all but weak excuses. To be sure, records show that despite being given ample time of 120 days reckoned from the time of the subject mark's publication to file its Opposition, TKCL still failed to exert diligent efforts to obtain the original documents. Worse, it never attempted to secure even just certified true copies of said documents. This attitude cannot in any way justify the relaxation of the Regulations.145

II.B. Admission and appreciation of Farling's evidence in the 1994 Cancellation Case and incorporation thereof as evidence in the Opposition Cases are proper and justified.

In the case at bar, taking into consideration the fact that the dispute has been pending for almost thirty (30) years, we sustain the IPO's evaluation of Farling's evidence in the 1994 Cancellation Case, more particularly the Republic of China trademark registration. Likewise, we find that the incorporation thereof as evidence in the subsequent Opposition Cases is in consonance with the RIPP and the general principles of administrative procedure. We also find that such incorporation did not violate Cymar's right to due process.